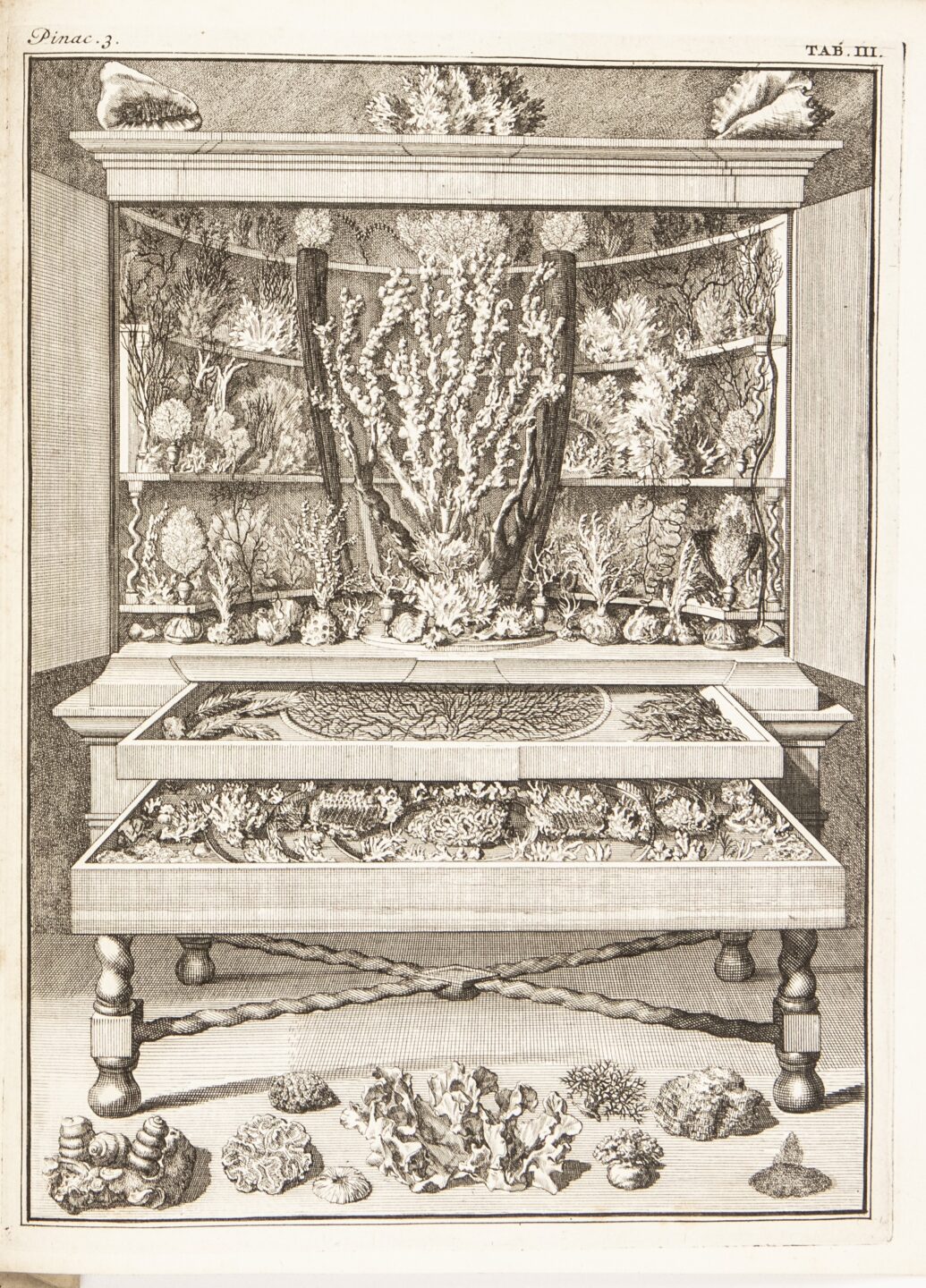

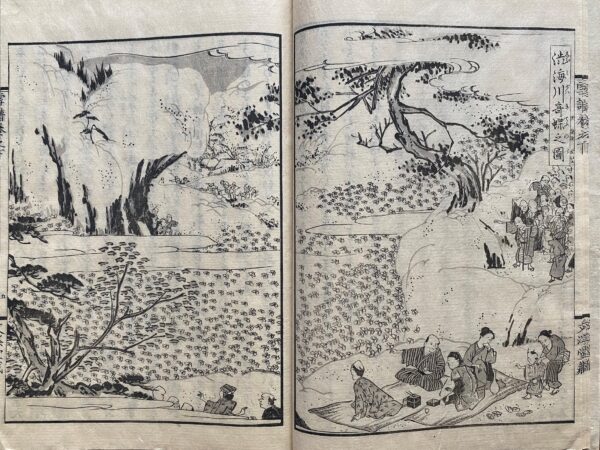

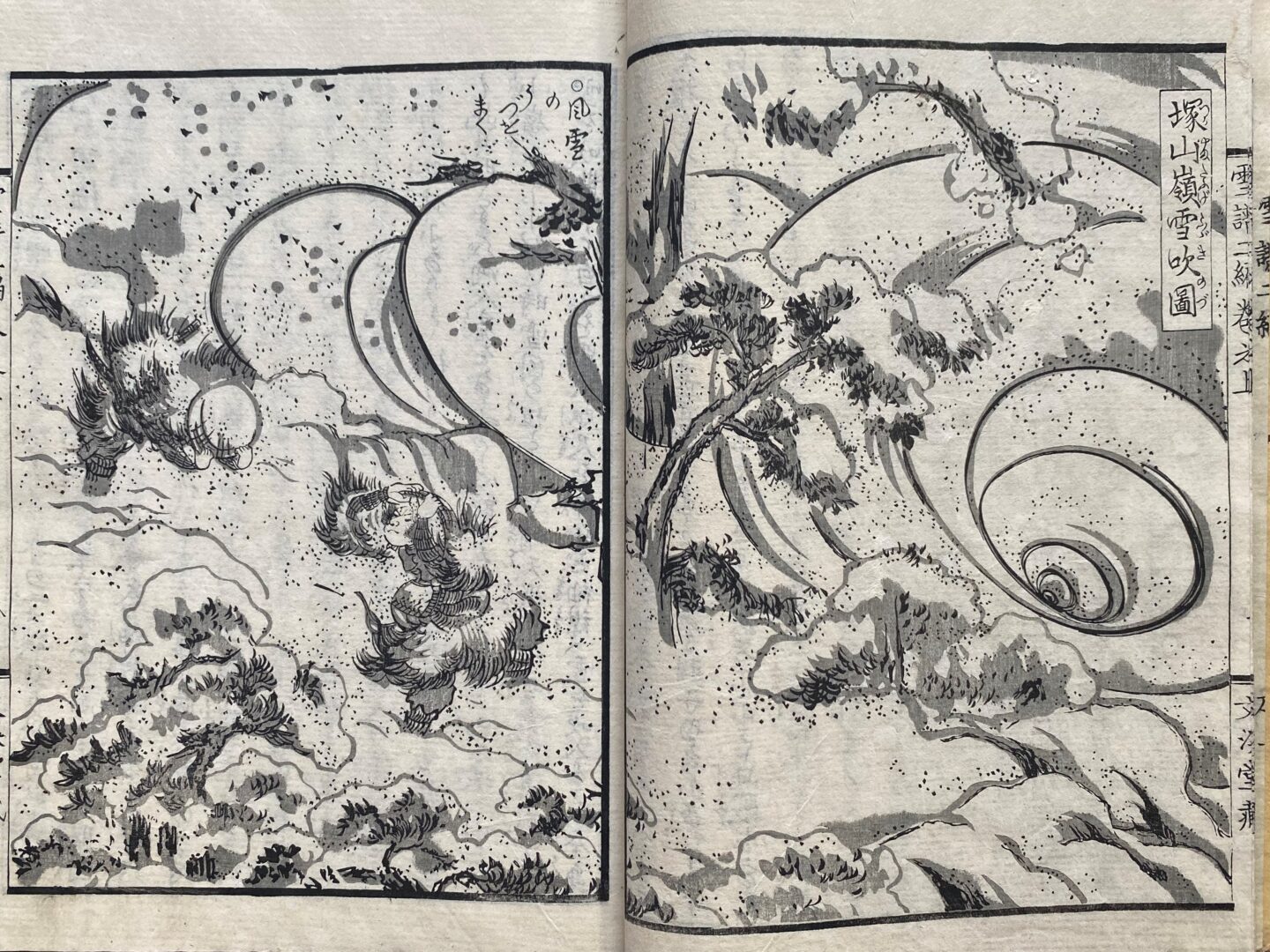

Wu, Youru 吳友如. Shenjiang sheng jing tu 申江勝景圖 : [2 juan]. Shanghai: Dian shi zhai, Guangxu 光緒10 [1884] 4 v. (double leaves : chiefly ill.) in case ; 25 cm.

NC1230.W8 View in Catalog

SCENIC VIEWS IN AND AROUND SHANGHAI

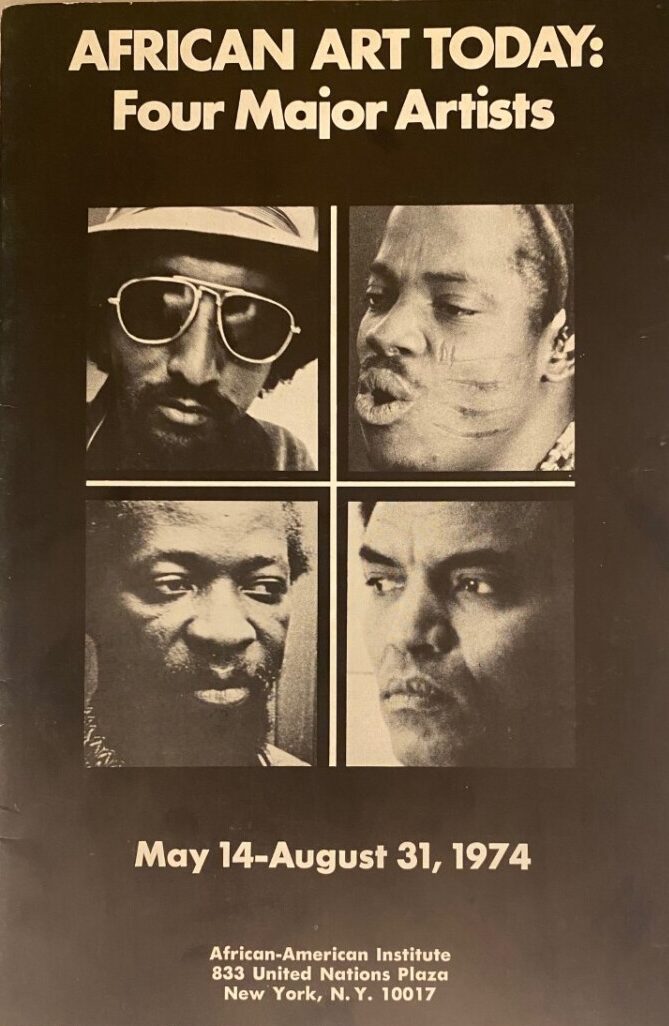

![Dianshizhai chubanshe, 光緒十年 [1884]. Dianshizhai chubanshe, 光緒十年 [1884].](https://library.princeton.edu/sites/default/files/news/images/Shenjiang%20sheng.jpg)

Opened in 1879 by former English shipping agent Ernest Major (1841-1908), the Dianshizhai Lithographic Printing House 點石齋出版社 in Shanghai introduced lithographic printing to China with presses imported from England. The publications of Dianshizhai stood out for the fine quality of their fonts, manageable size, and value.

Major had distinguished himself seven years prior to this by founding the first Chinese independent newspaper, Shenbao 申報 (Shanghai Gazette), which took for its primary audience the average Chinese reader. The only news sheet in regular circulation before this was the Peking Gazette, which was devoted to court and government news and written in a classical style virtually unintelligible to the ordinary person. Major’s innovations included keeping the paper low in cost to both readers and advertisers; the use of baihua 白話 , or everyday language; and printing articles that came, in the majority, from Chinese writers, and which were often critical of the government.

Helmed by Master Printer Qiu Zi’ang 邱子昂 , Dianshizhai Lithographic Printing House published a wide range of works, utilizing photographic technologies to reproduce classic texts from woodblock carved editions of the past. These included the comprehensive dictionary of Chinese characters, Kangxi zidian 康熙字典 reprinted in a smaller format; the early 18th century rhyme dictionary of literary allusions and poetic diction Peiwen yunfu 佩文韻府 (Rhyme Treasury of [the Studio for] Admiring Literature); a Chinese-English bilingual edition of Sishu 四書 (The Four Books), which detail the fundamental precepts of Confucianism, in addition to a variety of Western language books, collections of rubbings, and painting manuals.

Continue reading