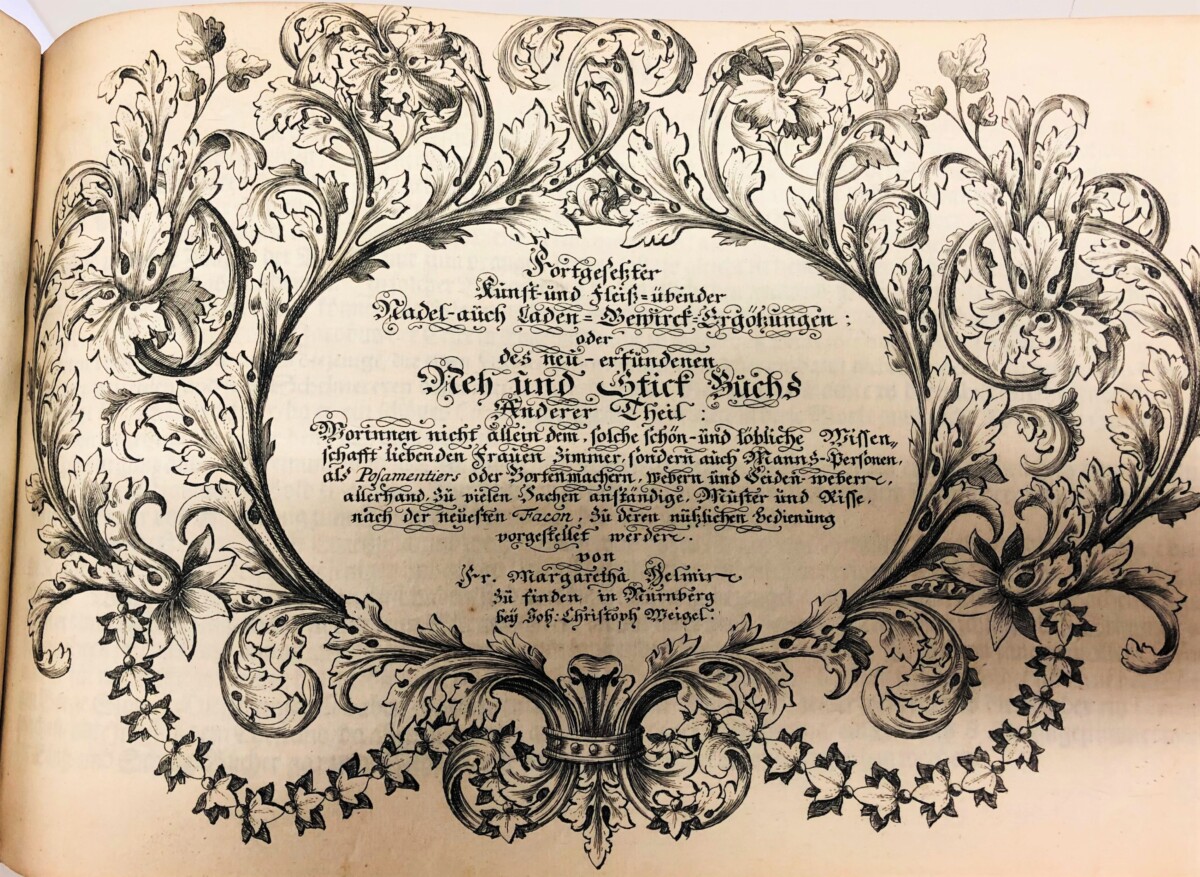

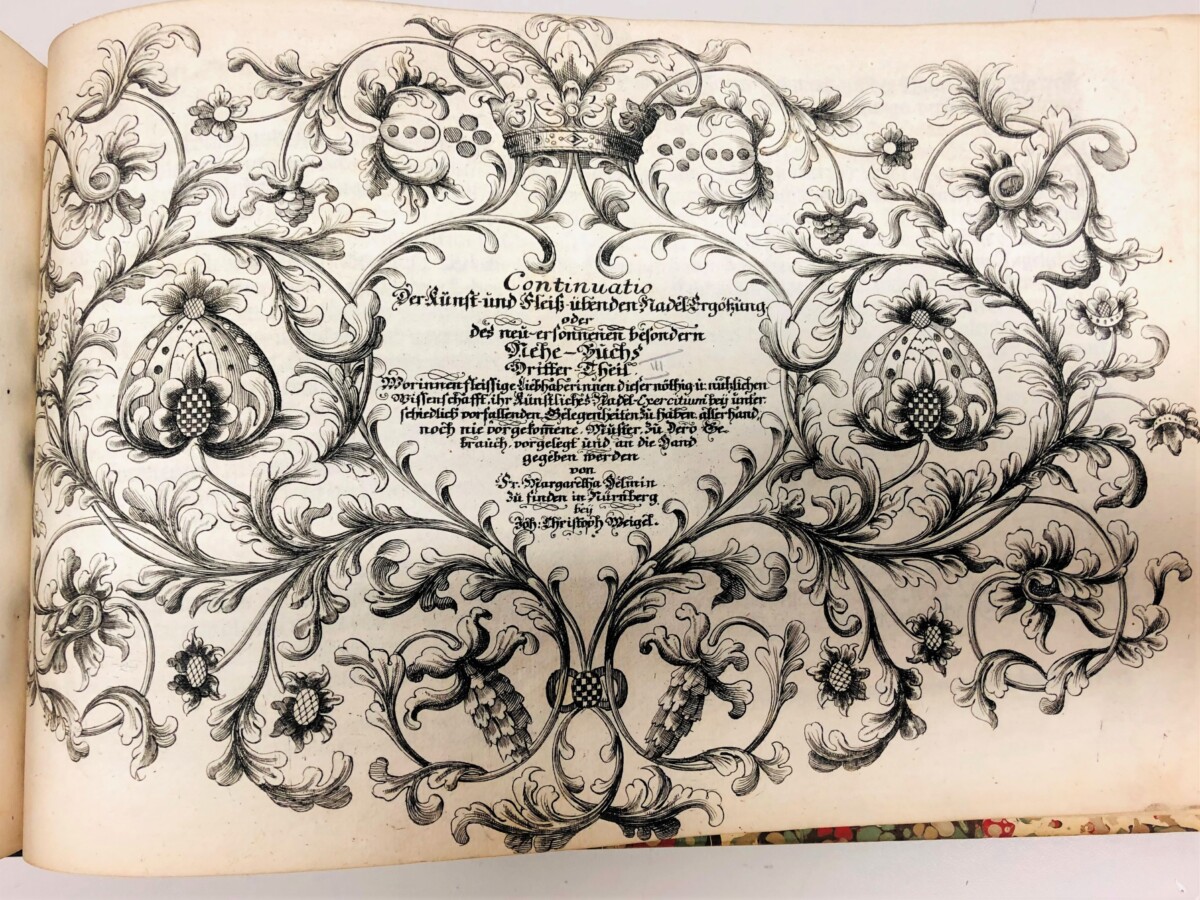

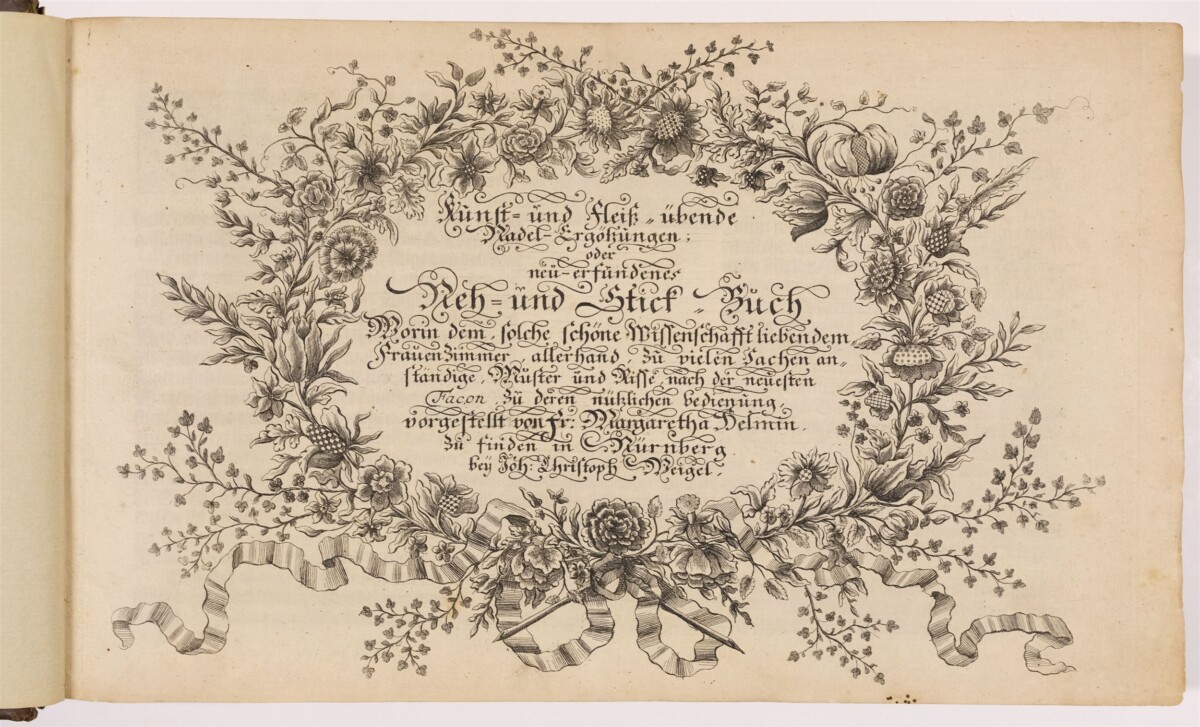

Kunst- und Fleiss-übende Nadel-Ergötzungen: oder neu-erfundenes Neh- und Stick-Buch [The Delights of the Art and Industry of the Practising Needle or the Newly-Invented Sewing and Embroidery Book], an early eighteenth-century German pattern book, was recently acquired by Marquand Library with generous support from other areas in PUL, including Rare Books, Graphic Arts, Gender & Sexuality Studies, and History. This collaborative acquisition reflects the insights into many areas of common interest that this publication provides. One of just a handful of surviving copies, this book is the work of Margaretha Helmin (Helm) (1659-1742). Born Margaretha Mainberger, she was a professional embroiderer, teacher, and copper plate engraver working in Nuremberg. Princeton’s copy, consisting of 3 parts with separate title pages, here bound together, probably dates to between 1742-1746.1

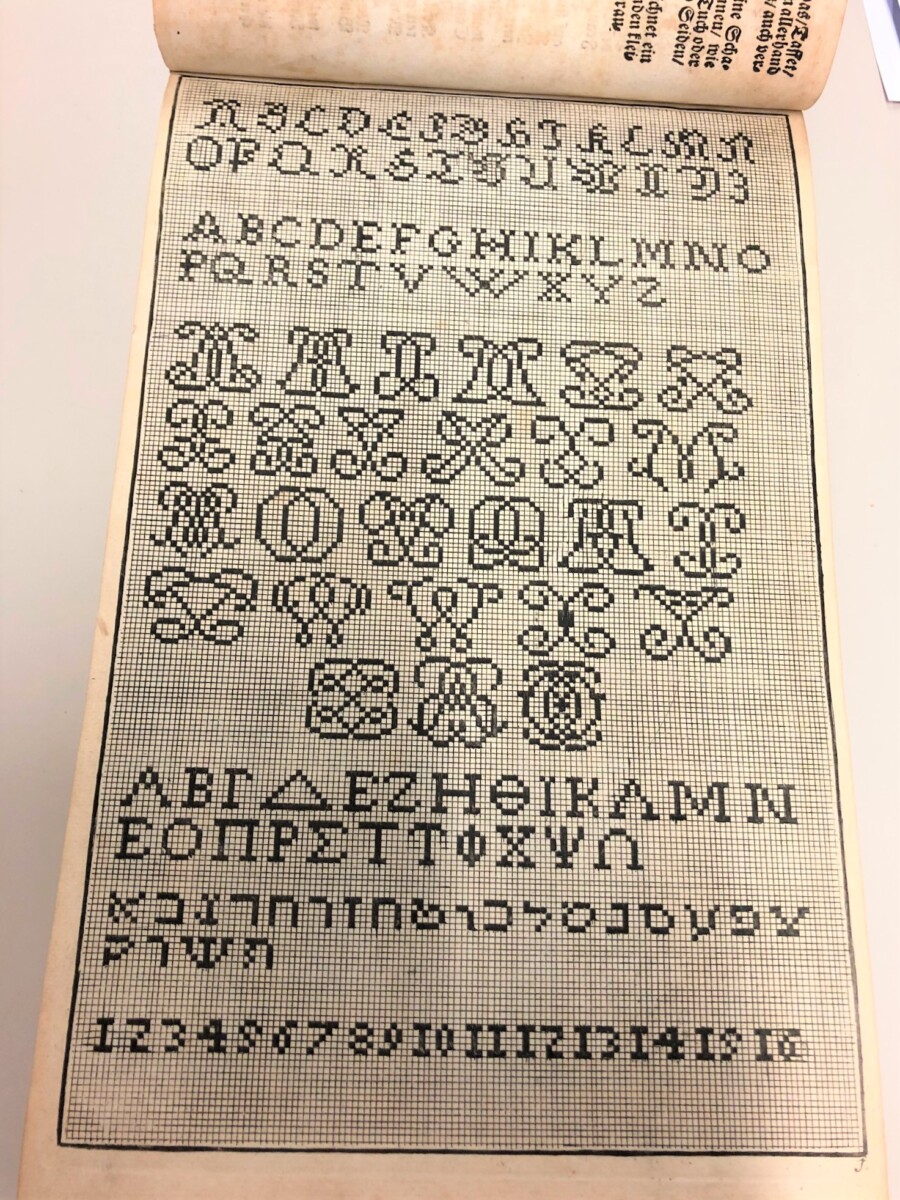

Printed pattern books and individual sheets of printed designs for embroidery, needlework, and lace, published in Europe since the sixteenth century, were used by both amateur embroiderers and profession workers, whose ranks included many men in the earlier period. The patterns could be used in various way — the outlines of designs could be pricked to create tiny holes through which charcoal dust was blown to transfer marks directly onto the fabric, or translucent (oiled) paper could be laid on top of the print for tracing from the original, or the prints could be copied by hand by those skilled at drawing. Many of these books and sheets were gradually destroyed by repeated use or were superseded by new designs. But embroidery patterns often survived the changes in fashion by being modified and reprinted for decades, as is the case with Margaretha Helmin’s designs. Some were her own invention but others derived from earlier publications.

Although this type of pattern book was often addressed to female readers, only a handful have been credited to female designers/authors, most notably Isabella Catanea Parasole’s Specchio delle virtuose donne (Rome, 1595). By the eighteenth century, the number of such books increased greatly, but women authors were still underrepresented. A published record of more than 300 notable artists and craftspeople working in Nuremberg in 1730 noted only 12 women, including Magdalena Fürst(in) “drawer and painter” and Amalia Pachelblin (1688-1723), a pattern drawer, flower painter, copperplate engraver, and embroiderer. Rosina Helena Fürst (1642-1709), the sister of Magdalena, also published a needlework pattern book in Nuremberg: Das Neue Modelbuch… (ca. 1660), republished in 1728 by Johann Christoph Weigel’s widow. In G.A. Will’s 1758 dictionary of notable men and women in Nuremberg, Helmin was finally mentioned as a teacher and publisher of embroidery designs, though she was probably active in this field since possibly the 1680s, when she would have been in her early twenties.2 The standing of all three women in their professions was sufficient to merit being included in records made after their deaths. Nuremberg, a thriving commercial city, famous for its printmaking and publishing, at least offered a network of contacts for such endeavors.

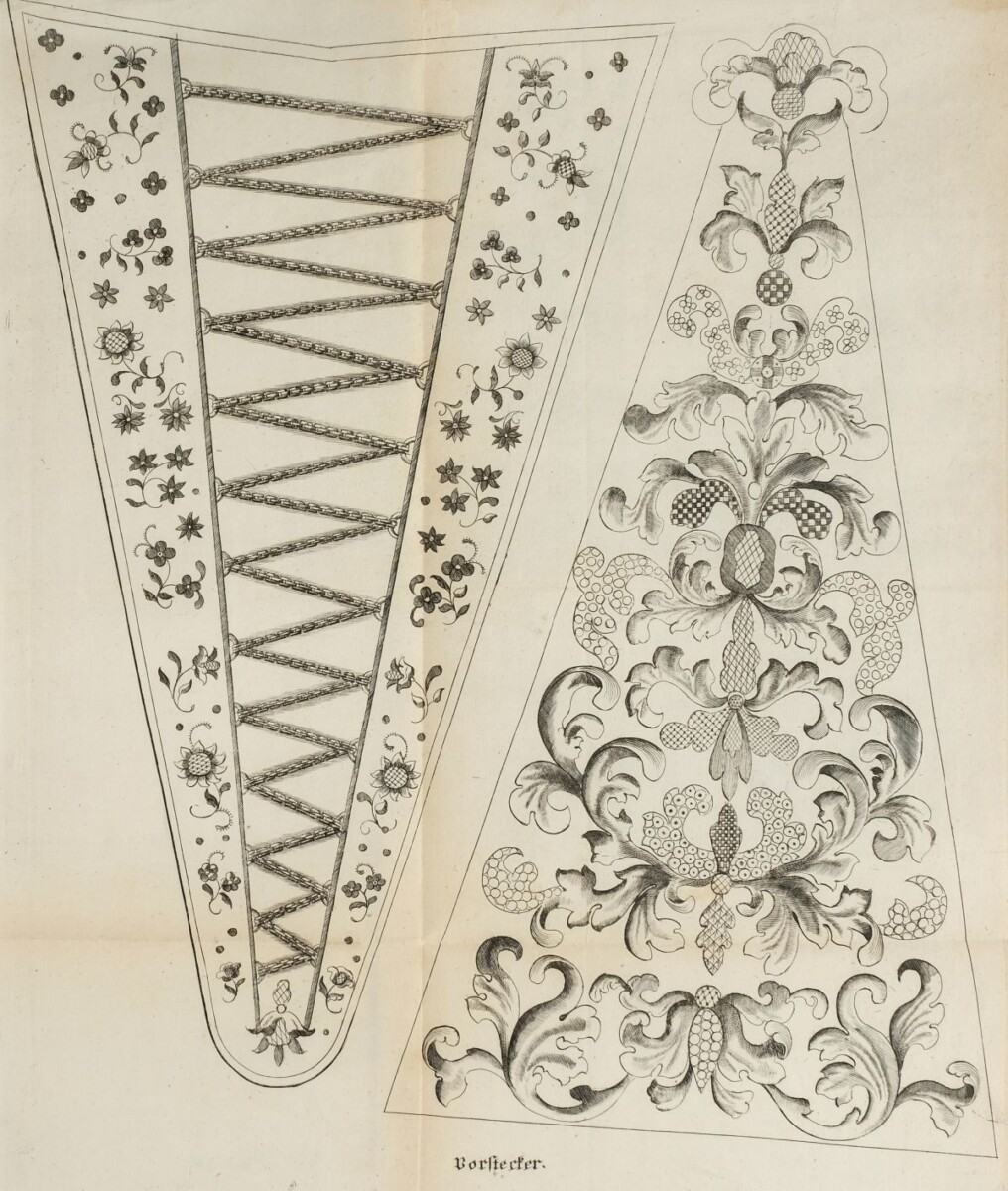

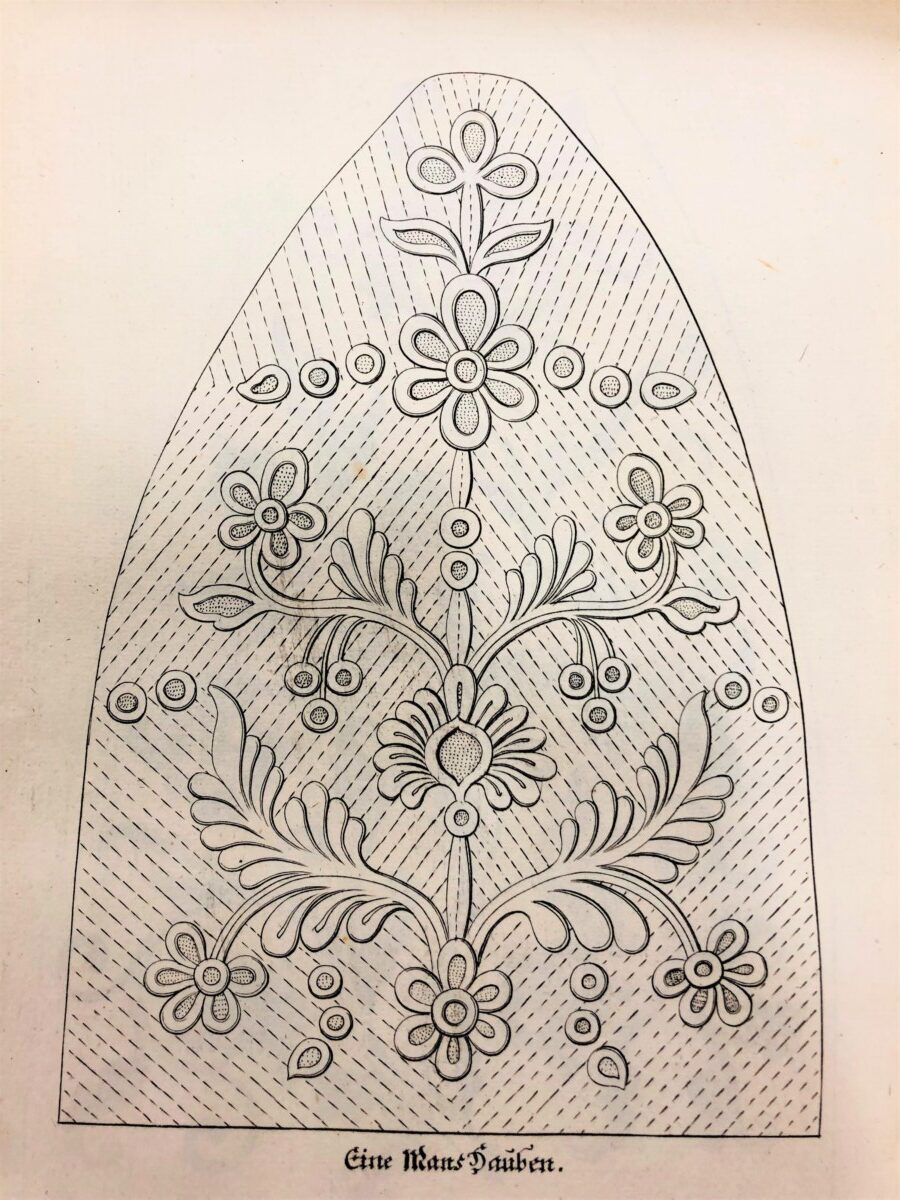

Helmin’s book, with 154 plates, some double-paged, many with multiple designs on each page, provided a wide variety of patterns that would have been used by both amateur and professionals. A page of alphabets would have been useful for young women to learn basic marking/initialing of their household linens for inventories and laundry, or for making samplers to practice their stitches, if they had more leisure time. But most of the designs, such as the intricate vase of flowers and embroidered pictorial fan illustrated here, were much more advanced and required a higher level of skill with the needle. Other plates offered sections of ornament that could be repeated to decorate a variety of interior furnishing, including covers and cushions. The second part also included designs that were also suitable for weaving patterns.

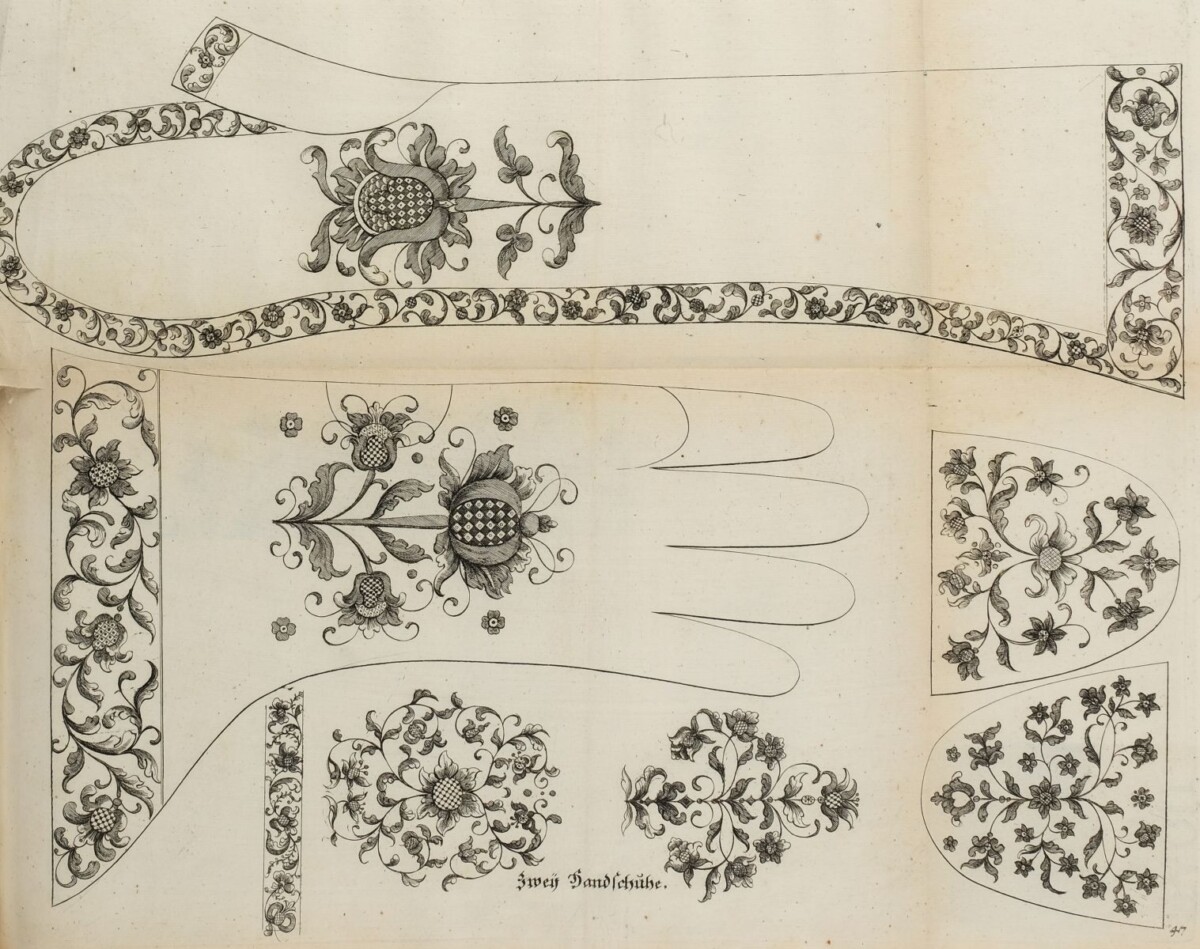

Examples of surviving textiles, sometimes including embroidered dates, and surviving garments with similar designs in museum collections help to provide closer dating for some of Helmin’s patterns. Items of clothing, such as jackets, and costume accessories, such as stomachers, caps, gloves, fans tended to survive as keepsakes, and some examples compare closely with the prints.

The pattern above shows designs for a gloves for both women and men. Luxurious gloves were popular New Year’s gifts in the early modern period. Queen Elizabeth I of England received and gave many gifts of elaborately ornamented and perfumed gloves (sometimes containing gold coins) during these celebrations. If you managed to read to the end of this post, all in Marquand Library wish you ReMarquable holidays and a happy and healthy New Year!

Nicola Shilliam, Western Art History Bibliographer

- In the forward to part 2 of Princeton’s copy, there is a reference to Adam Helm, Helmin’s husband, as cantor of St. Egidien in Nuremberg, a position he only held from 1742 until his death in 1746. Johan Christoph Weigel the Younger may have reprinted or republished older stock of parts of Margaretha Helmin’s work, possibly published by his father Johann Christoph Weigel the Elder, who died in 1725. The parts were published as needed, which may account for the lack of assigned dates.

- For much more on this topic, please see: Moira Thunder, “Deserving Attention: Margaretha Helm’s Designs for Embroidery in the Eighteenth Century,” Journal for Design History (2010) vol. 23, no. 4: 409-427.