https://catalog.princeton.edu/catalog/99107157823506421

In 2020, the controversial “Brexit” finally severed a relatively new (less than fifty years) bond between Britain and Europe. Marquand Library recently acquired an unusual item that recorded a much earlier, even more tumultuous change in the relationship between England and mainland Europe: a scrolling facsimile of the Bayeux “Tapestry” depicting the Norman invasion of England almost one thousand years ago.

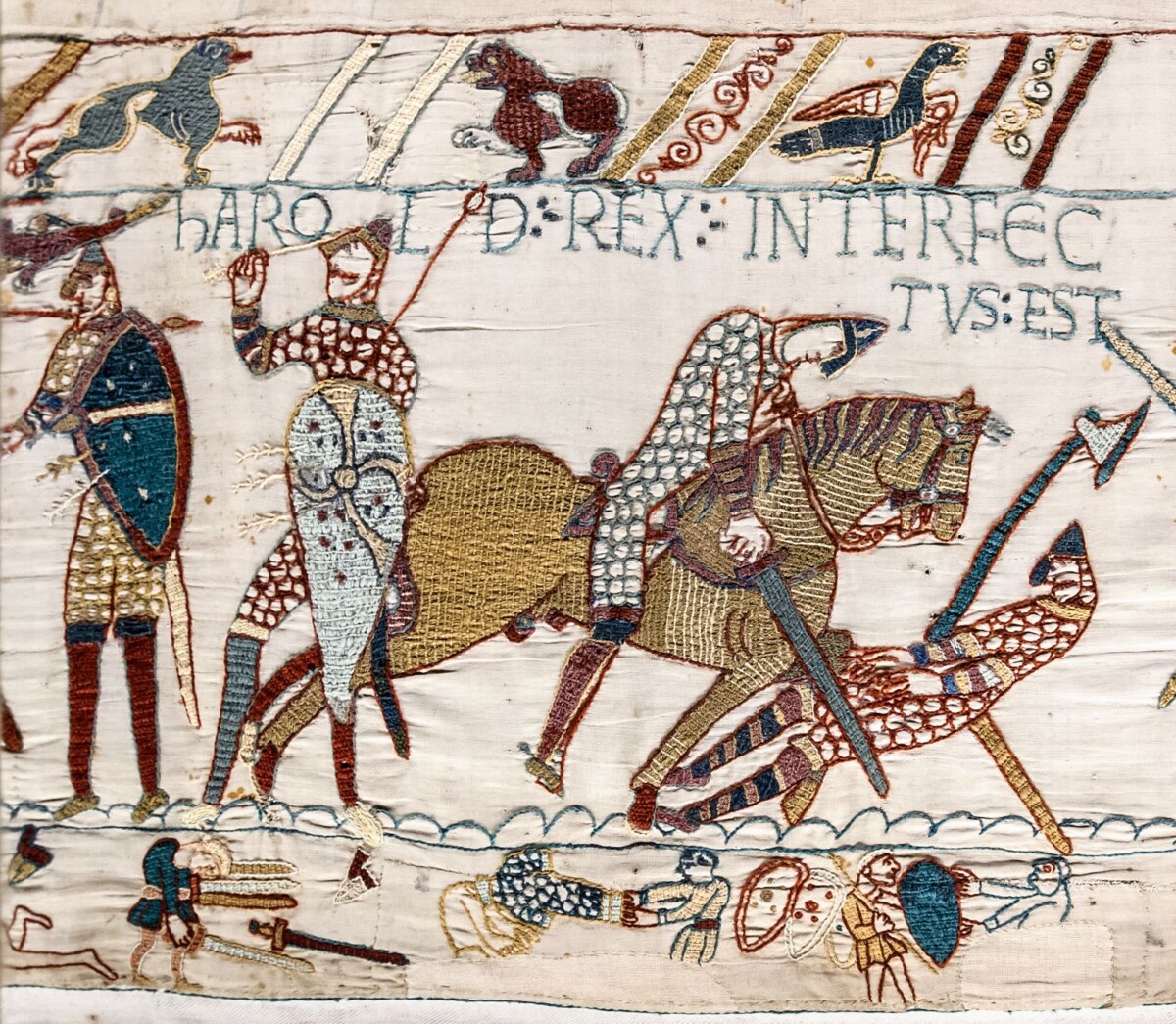

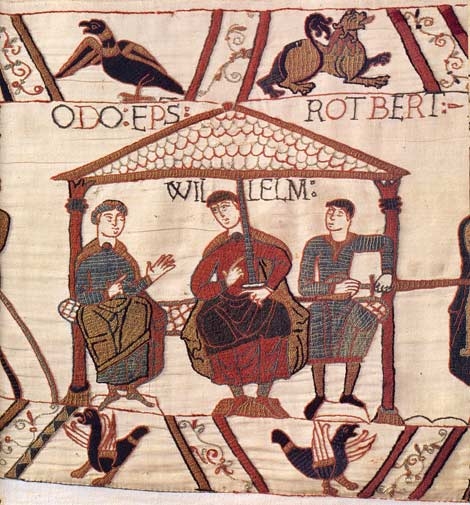

The events leading up to and narrating the Battle of Hastings in 1066, when Duke William of Normandy crossed the Channel to assert his claim to the English throne, are depicted in vivid scenes of battle, feasting, sea travel, and the deaths of two kings (Edward and his successor, Harold). Yet these images, executed in the Romanesque graphic style of the 1070s are embroidered rather than painted. In spite of its commonly used name, the Bayeux “Tapestry” is technically not a tapestry, since the imagery is not woven on a loom but embroidered in natural-dyed wool yarns onto a linen ground fabric. This pictorial textile scroll, consisting of a continuous narrative of scenes with embroidered captions, meant to be read from left to right, measures almost 70 meters (230 feet) long and 50 cms (19 inches) tall, and is a glorious testament to the work of medieval embroiderers.

Although traditionally ascribed to the hands of Queen Matilda, William’s wife, and her attendants, the identity of the embroiderers remains unknown. It is likely that the work was commissioned by Bishop Odo of Bayeux, the William’s half-brother, a warrior-cleric who also acted as regent in the absence of the king. The embroidered narrative would have served both as a powerful piece of dynastic propaganda and to glorify Bayeux Cathedral, in Normandy, consecrated in 1077 in the presence of King William.

For nearly seven centuries, the embroidery was preserved in relative obscurity there, being displayed only once a year – which helped preserve this fragile textile relic. The first recorded mention of the Bayeux embroidery was in an inventory of the cathedral Treasury in 1476.

In the 1720s, sketches of the Bayeux embroidery came the attention of the scholar Bernard de Monfaucon, who published images of the scenes in his multi-volume Les monumens de la monarchie françoise, qui comprenant l’histoire de France…. (1729-1733). https://catalog.princeton.edu/catalog/9923172793506421.

Since 1805, when Napoleon commanded that the embroidery be brought to Paris as he contemplated his own invasion of England, the work has assumed iconic status. During World War II, the textile was carefully stored by the Nazi occupiers with other works of art in France, after which it was briefly shown to the public in the Louvre before returning to Bayeux, where it has since been on display in the former Seminary. It has acquired wider fame in recent years – referenced in movies (such as The Monuments Men), in cartoon form – in an episode of The Simpsons, and in an animated version, viewable online, where arrows fly and horses gallop. Princeton’s copy of this remarkable facsimile permits much closer examination of details than is possible when visiting the actual artwork today, since its fragile nature requires low light levels to help preserve the fibers and colors. This facsimile has already been studied by students in classes on medieval art in Marquand’s rare books classroom.

To view the entire facsimile as it is unrolled, use the link below. Warning: this video is accompanied by dramatic (and possibly loud) music!:

The original textile is on display in the former Seminary in Bayeux, France. Plans to lend it to the British Museum for display this year appear to have been postponed. For much more information about this extraordinary work of medieval art, see the Bayeux Museum website.

Nicola Shilliam, Western Art History Bibliographer