Marquand Library recently acquired a copy of Signa antiqua e museo Jacobi de Wilde veterum poetarum carminibus illustrata et per Mariam filiam aeri inscripta. Amsterdam: Jacob de Wilde, 1700

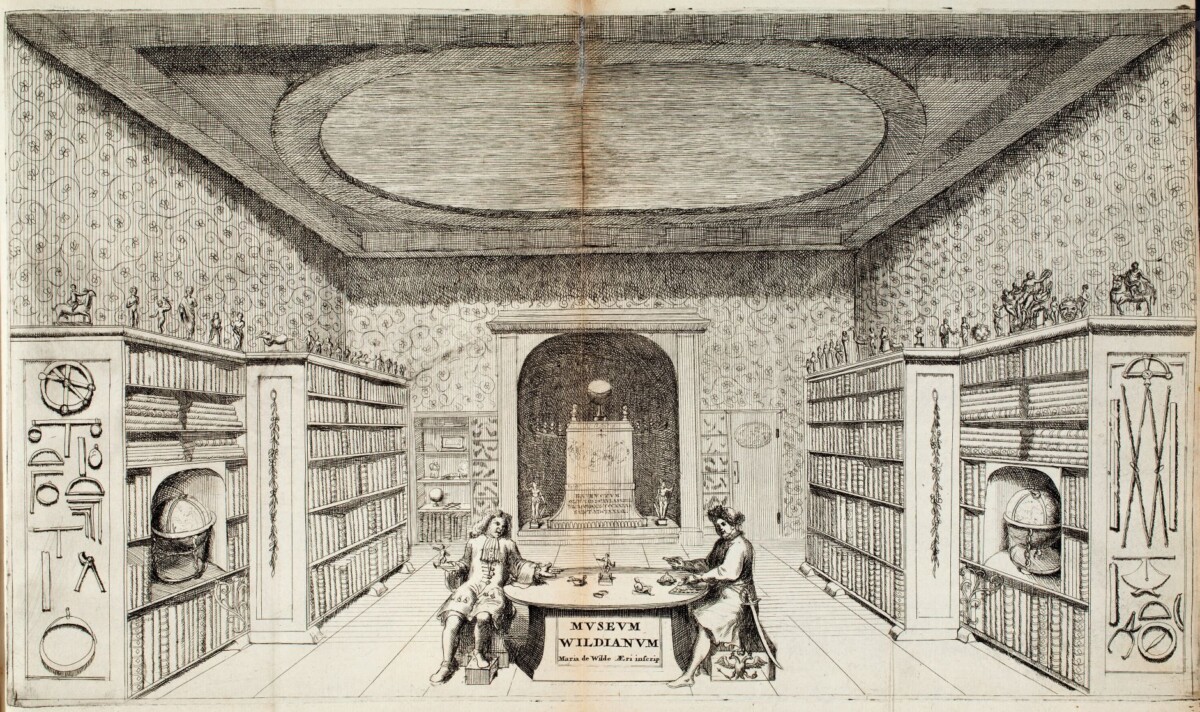

Signa antiqua is a catalogue of part of the private collection of antiquities assembled by Jacob de Wilde (1645-1721), the prosperous Collector-General of taxes for the Admiralty in Amsterdam. In an era before the establishment of public museums, de Wilde was one of a small group of wealthy and educated amateurs who collected, sometimes published on, and invited guests to view and study their treasures. De Wilde’s interests were more focused on antique objects – Egyptian and Roman statuettes, vases, and coins – than on the diverse mix of both natural and man-made specimens found in most Wunderkammern (cabinets of curiosities) [See an earlier blog posted here on this topic.] The Museum Wildianum, built by de Wilde behind his home in Amsterdam on Keizersgracht 333 and extending to the houses nearby, was viewed by hundreds of distinguished visitors.

Statuettes of Mars and a Sphinx, two illustrations for Signa antiqua…,etched and engraved by Maria de Wilde after her drawings of objects in the Museum Wildianum .

What is particularly noteworthy about this book is how much de Wilde’s teenage daughter contributed to the publication. Maria de Wilde (1682-1729) was responsible for the illustrations: 60 etched plates after drawings she made from her study of the objects in the family’s museum. This may be the first catalogue of a private museum collection known to have been illustrated by a woman. Maria’s privileged upbringing and enlightened parents enabled her to pursue her diverse talents – drawing, painting, and engraving; singing and playing the lute; composing poems, and even publishing a play.

Judging by the accurate captions in her prints and the lavish tributes written by learned acquaintances, such as the dedicatory poems by Adriaan Reland and others n the catalogue, she was almost certainly fluent in several languages. In addition, Johannes Brandt (1660-1708), a poet and family friend, as well as the pastor of the nearby Remonstrant church, also praised her “thirst for science.” Maria took lessons in etching and engraving from Adriaan Schoonbeek, a pupil of Romeyn de Hooghe, and from Pieter van den Berge. Maria’s portrait, above, was etched by van den Berge and accompanied by an emblematic verse of praise by David Hoogstraten.

One of the most distinguished visitors to the Wilde collection was Tsar Peter the Great, whose trip to the Museum on December 13, 1697, was commemorated by a print that Maria made and later included in the book. In addition to the specimens, globes and measuring tools, a large collection of books lines the walls of the museum. On the Tsar’s second visit in 1716, Maria presented him with the print, and he made her a gift of a jewel.

A second volume recording de Wilde’s collection, Gemmae selectae antiquae e museo Jacobi de Wilde..., was published in 1703, though the extent of Maria’s participation in that publication is yet to be resolved. However, with many contacts in the scholarly community, Maria was one of the few female artists whose work appeared in several academic publications: two of her prints also appeared as illustrations in Adriaan Reland’s Dissertatio altera de inscriptione nummorum quorundam Samaritanorum: ad spectatissimum virum, Jacobum de Wilde… [1704].

Immersing herself completely in her work, Maria adopted the motto “Sine Pallade Nihil” and avoided a conventional early marriage. Andreas Lang, a visiting German poet, praised her talents in a Latin poem (1705), though lamented that she was not interested in him as a suitor. In Lang’s 1707 birthday poem celebrating Maria, he warned that no one should bring up the subject of marriage because she was “engaged to Apollo” and produced “adult paper children.” Yet, in 1710, Maria did marry. That same year, she published Abradates en Panthea, a tragedy. Though the work appeared anonymously, the accompanying poems of praise easily identified her as the author. Although other literary works have been attributed to her, nothing dating after her marriage has been authenticated. Likewise, except for the published prints, none of her art works have been identified. In 1729, Maria was buried in Amsterdam’s renowned Oude Kerk, in a plot bequeathed by father in his will. She was survived by at least one daughter, Jacoba Woutrina (born 1719).

Nicola Shilliam, Western Art Bibliographer,