*

“It is said that if one natural disaster strikes, a second will occur…“

*

So begins the preface to Natural Disasters of the Ansei Period [Ansei fūbunshū], a harrowing chronicle of disasters that took place in Japan during the first two years of the Ansei period (1854-1860). The era was beset with natural calamities: four major and many minor earthquakes, two tsunami, flu and cholera epidemics that killed hundreds of thousands of people, and a typhoon in 1856. The main focus of this book, however, is the typhoon and the subsequent flooding that took 10,000 lives and wiped out much of northern Edo (present-day Tokyo) and the Izu peninsula. The author, popular fiction writer-turned-journalist, Kanagaki Robun (1829–1894), blends eyewitness accounts, religious and mythological interpretations of events, and powerful images to report these tragic events of the day.

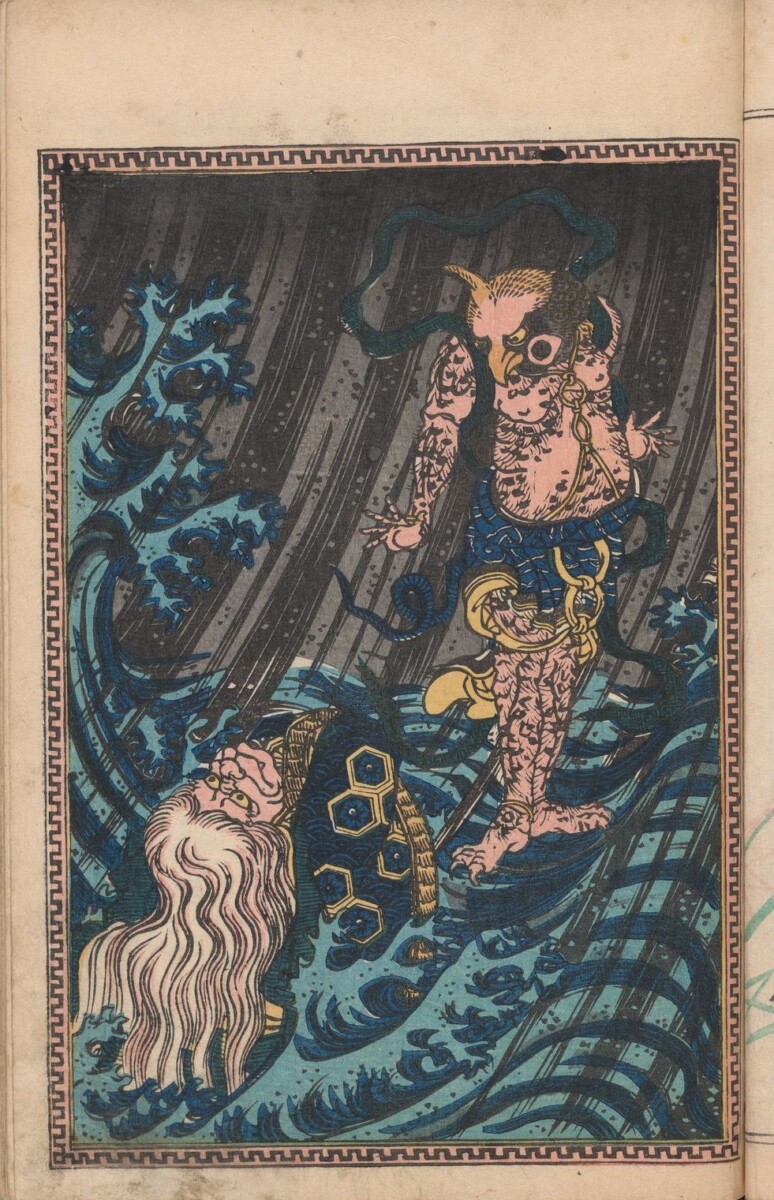

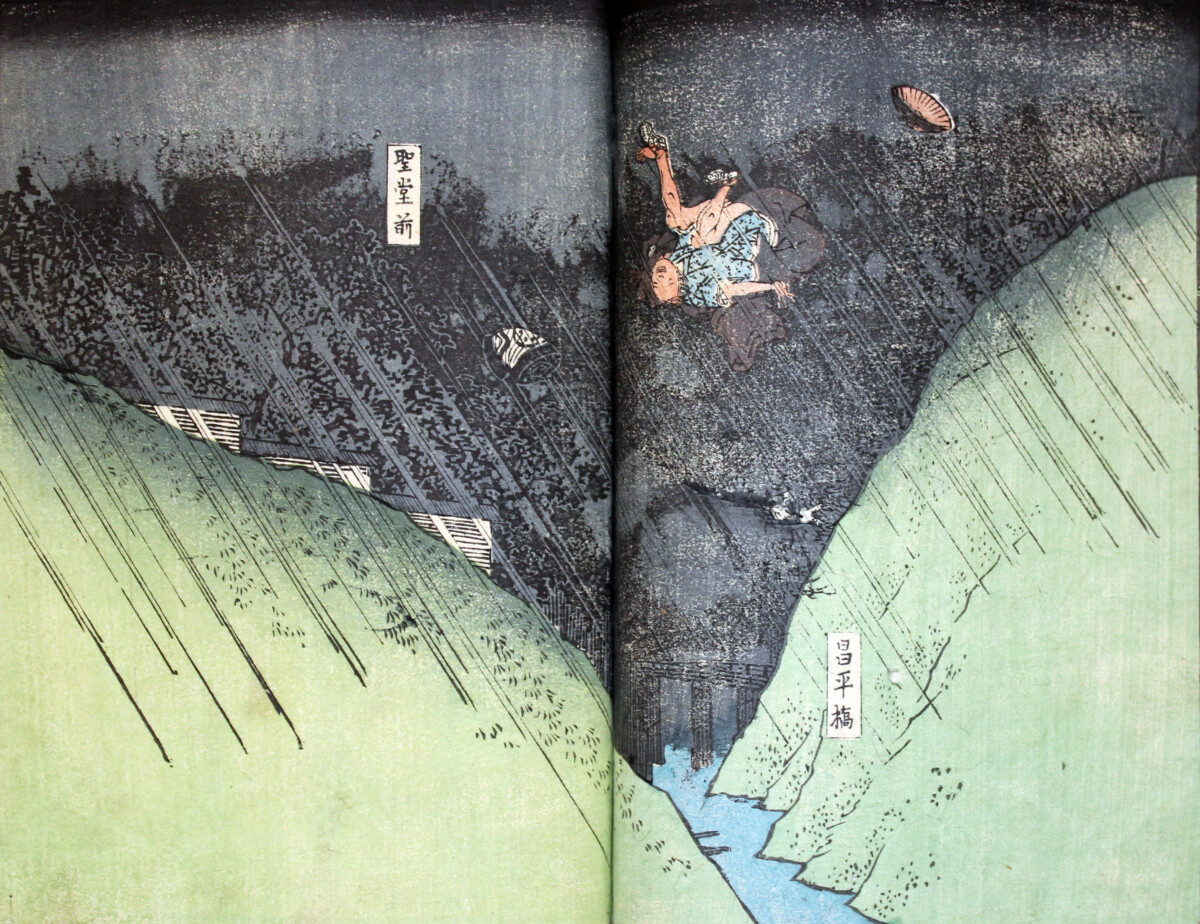

Hiren, the Chinese God of Wind, hovers above an elderly drowning woman in the first illustration for volume 1. Known as a troublemaker, he carries his destructive winds with him in a bag. Robun warns that this image might frighten children.

Many blamed the spate of natural disasters on the arrival of American commodore, Matthew Perry, and his “black ships” in 1853 and again in 1854. Perry forced Japan into trade agreements with the West, ending over two hundred years of self-imposed isolation. Some welcomed the changes that contact with the West brought to Japan, calling it “Modernization.” Others did not, and they believed the earthquakes, tsunami, and floods should be interpreted as a sign that the indigenous Shinto gods (kami) were displeased with this new relationship with the West.

***

Very little is known about the making and distribution of this three-volume set. This is undoubtedly because the books were published illegally.

The Typhoon

The printing of books and woodblock prints was strictly regulated from the early 18th century in Japan. Influenced by the Neo-Confucian teaching that everything should be peaceful and uneventful during the reign of a virtuous government, the Tokugawa Shoguns believed that there was implied criticism in the discussion or publication of anything that might be considered “newsworthy.” They were especially sensitive to criticism that they had unnecessarily capitulated to the Americans when they agreed to trade with Western nations.

To control the publishing industry, all books and prints issued during the Ansei Period were required to include the names of the author(s), artist(s), and the name and address of the publisher. They also required approval from a government censor before publication. Non-compliance could mean public handcuffing or exile for all parties. Publishers, however, often flaunted these laws in books like Natural Disasters of the Ansei Period, and left out publication information. Authors and artists would also use pseudonyms to sign their work. Here, Kanagaki Robun uses the alias Kinton Dōjin.

In this scene, the wind from the typhoon is so strong that a man is blown off a mountain near the Shoei Bridge in the Chiyoda section of Tokyo. The Seidō Temple is just visible in the background. This site, one of Hiroshige’s famous 100 Views of Edo, was well known to the very literate Japanese audience. Seeing it manipulated by the artist in this way must have made the visual impact of this scene all the more shocking.

Kanagaki Robun and his publisher were well aware of the dangers of publishing Natural Disasters of the Ansei Period. Months earlier, Robun’s had published another book chronicling a massive earthquake that occurred in 1855.1 It was not only banned by the Shogun after publication, but the artists, the block cutter and the printer were all required to surrender their earnings and pay steep fines. The publisher was banished from his residence. However, as reported in the contemporary diary, Fujiokaya nikki,2 Kanagaki’s anonymity saved him from being punished. It is probably not surprising then, that in an attempt to appease government censors, Kanagaki begins this book declaring that natural disasters are the fault of nature–and not the result of discord or ineffectual rule. Still, no chances were taken with the publication of Natural Disasters of the Ansei Period, and those involved in the publishing process remained anonymous.

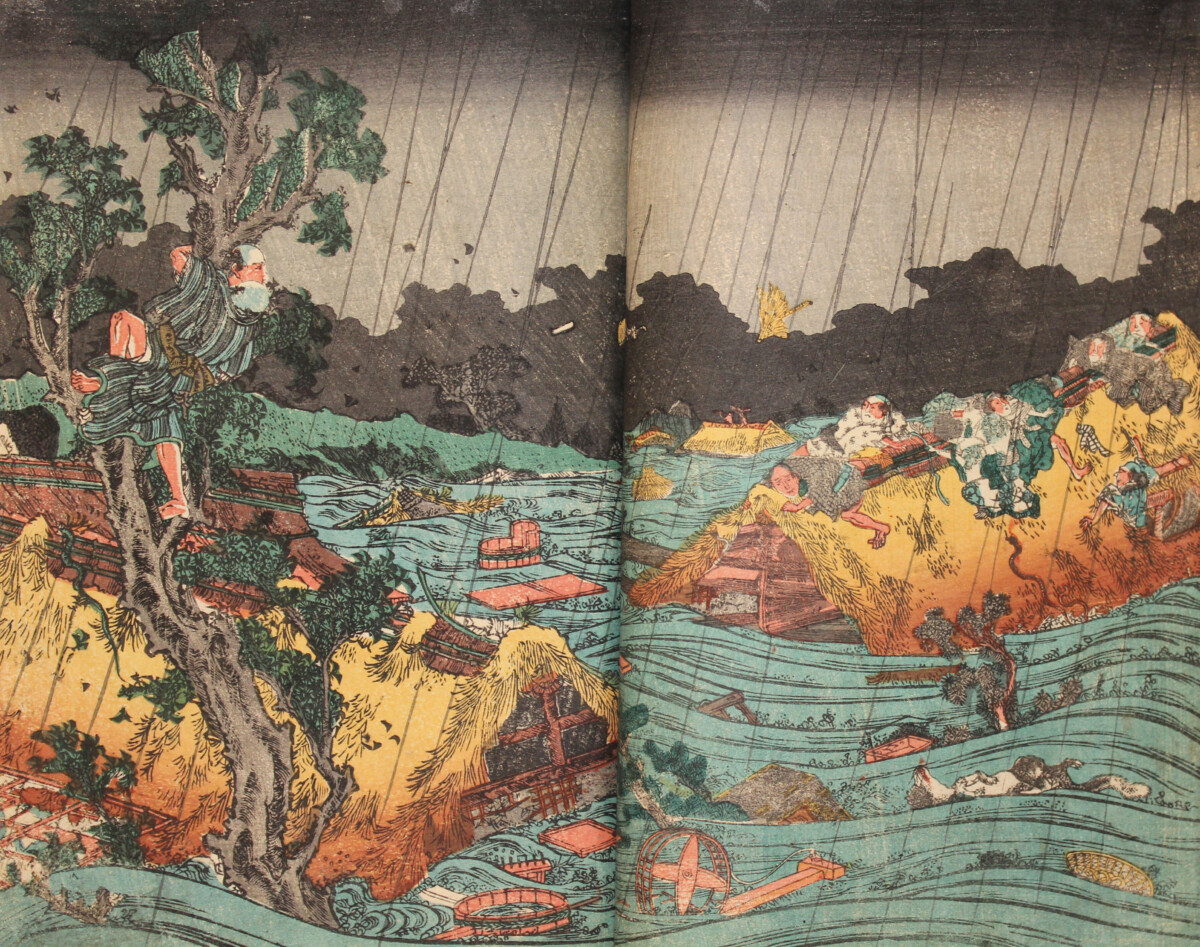

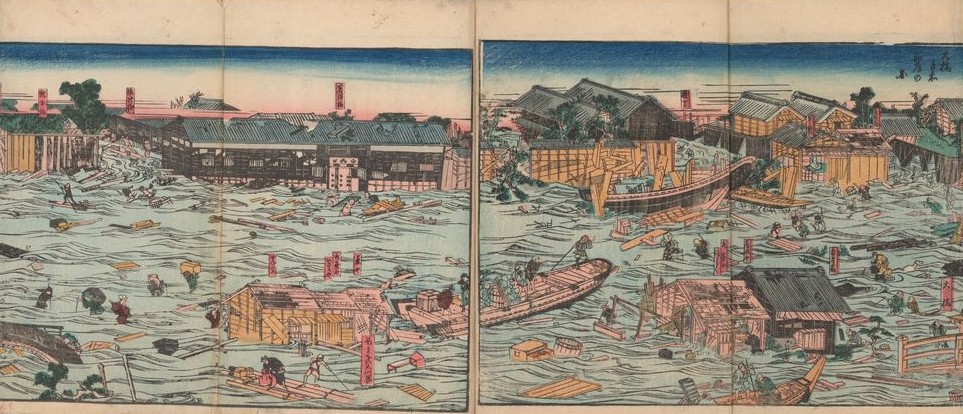

In volume 2, we learn about the many districts of Tokyo that were flooded by the Sumida River during the typhoon. This is a fold-out view of the neighborhood of Ryōgoku after the storm. The red cartouches are inscribed with the names of the different shops and businesses that were destroyed, giving this scene an almost documentary quality.

It is difficult to attribute the illustrations in these volumes to a single artist. In Kenji Toda’s 1931 annotated catalog of the Japanese book collection at the Ryerson Library of the Art Institute of Chicago, he reports that their copy is signed, “Utagawa Yoshitsuna” (act. 1850-1860’s), one of the artists fined for designing the woodblock prints for Kanagaki’s earlier earthquake chronicle.3 Although this has become the traditional attribution, the illustration of the man falling from the mountain (above) is signed Mitsuchika Mori (n.d.). It is therefore possible that, like its predecessor, Records of What Was Seen and Heard in the Ansei Period, there were several artists were employed to illustrate this set of books.

This double-page spread illustrates a personal account from a sailor aboard a boat that got caught in the typhoon. As the crew was managing to keep the damaged vessel afloat, the anchor cable of a much larger ship suddenly appeared before them in the water. Crashing into this heavily-weighted cable would have meant total destruction and loss of life, so the sailor decided to jump into the churning sea to cut it free with his knife. He saved both the boat and the sailors on board from any further harm before being pulled to safety with the rope he has tied around his waist. It is interesting that while many illustrations in this book are panoramic views of the storm’s destruction, the artist here has chosen to depict this story by focusing on one climactic moment.

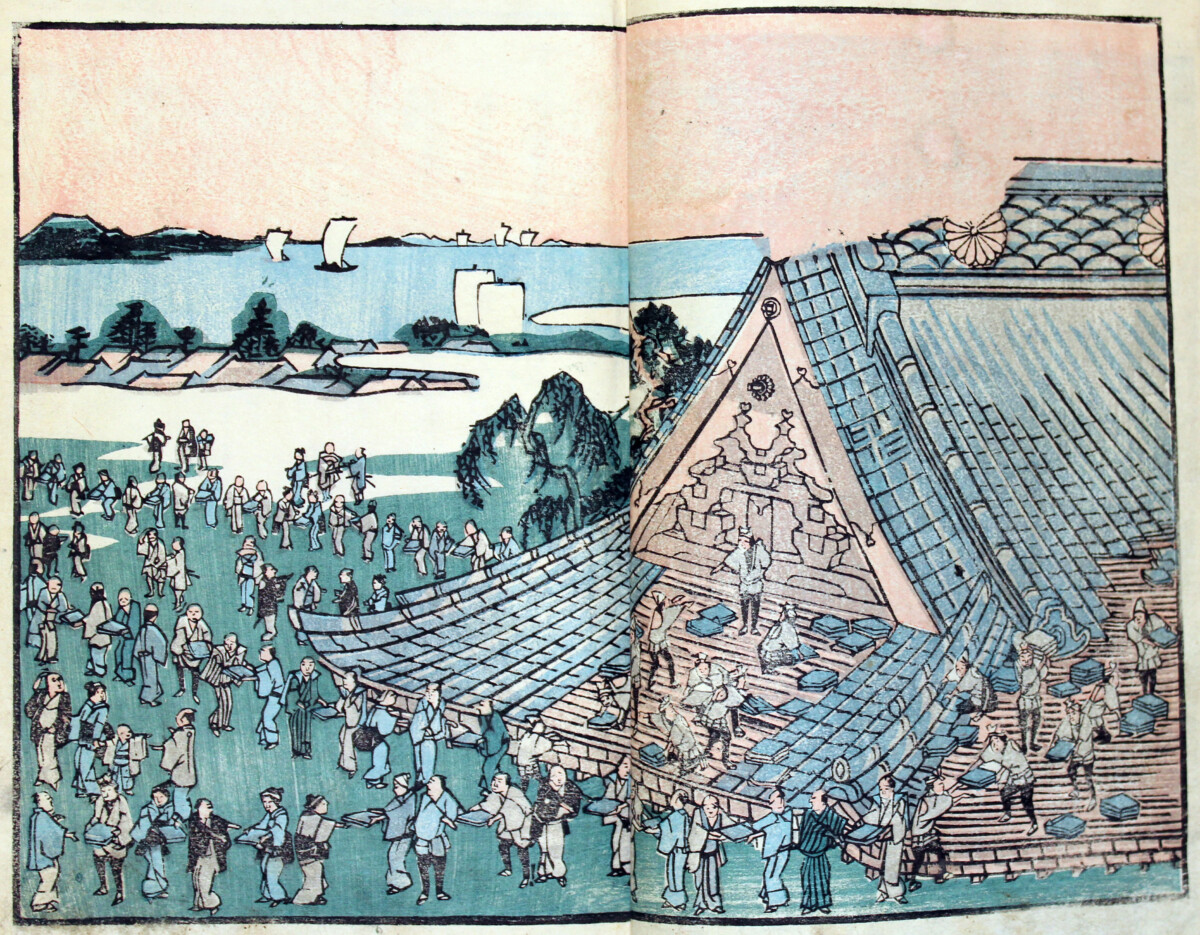

In this scene, repair of the roof has begun on the Teppōzu Inari Shrine, providing work for hundreds of men. The shrine still exists today in Tokyo.

It is interesting that in the third volume of Natural Disasters of the Ansei Period there was also a perceived positive side to catastrophes of the era in Japan. People, who didn’t have much to begin with, began to receive charity for the first time from both the government and wealthy merchants. Carpenters, blacksmiths, and other craftsmen profited greatly from the reconstruction of Edo and its environs. In later years, the destruction caused by the Ansei disasters was described as means to begin anew, to set the wheels in motion for the restoration of imperial rule in 1868, and to bring Japan into the modern age.

- Nicole Fabricand-Person, Japanese Art Specialist

- The book was titled, Ansei kenmonshi [Records of What Was Seen and Heard in the Ansei Period], published 1855-1856. ↩︎

- The Fujiokaya Diaries, which date from 1804 to 1868 are a major source of information about the culture (including crimes) of the Edo period. They were written by merchant and bookseller Sudō Yoshizō (b. 1793), using the pseudonym Fujiokaya. See: Tōzō Suzuki and Shōtarō Koike, eds., Fujiokaya nikki. Tōkyō : San’ichi Shobō, 1987-1995. ↩︎

- Kenji Toda, Descriptive Catalogue of Japanese and Chinese Illustrated Books in the Ryerson Library of the Art Institute of Chicago. Chicago: [Printed at the Lakeside Press, R. R. Donnelley & Sons Company], 1931, p. 295. ↩︎