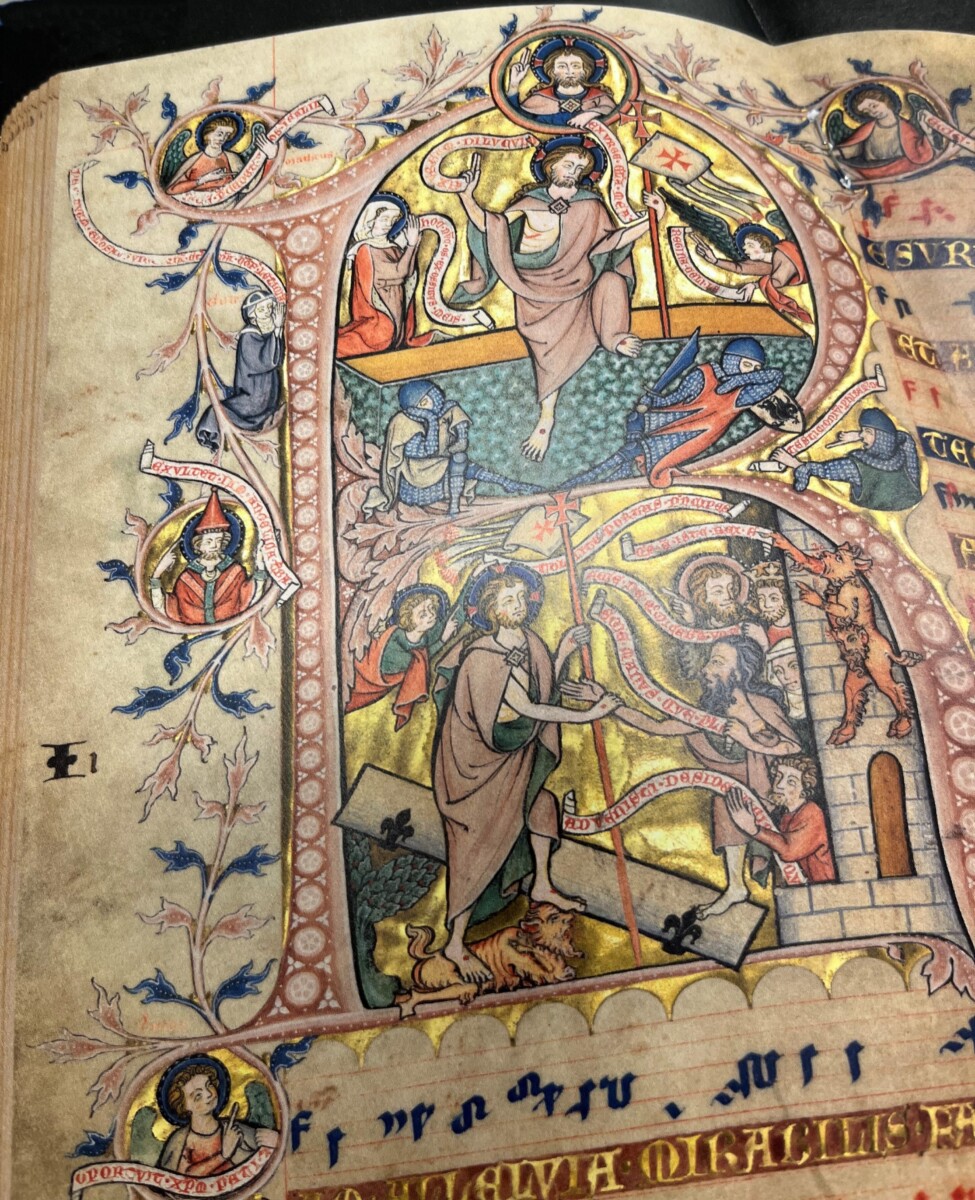

Medieval illuminated manuscripts were produced collaboratively by groups of artists and craftspeople – including scribes, illuminators, pigment and parchment preparers, and book binders – whose identities were usually unrecorded. Though some of these manuscripts have been attributed, usually by stylistic comparisons, to named artists, only a few are documented as the work of a particular hand, and that hand was usually male. One notable exception is a named woman whose work was recorded in a book of sacred music, known as the Gradual of Gisela von Kerssenbrock, before her death in 1300. Gisela, identified by name (“Gisle” written in red above her head), is shown here in a detail from the initial letter introducing the music for Advent, one of fifty-three large historiated initials that decorate the manuscript. Though the original manuscript is now conserved in the Diözesanarchiv, Osnabrück (Inv.-Nr. Ma 101), a facsimile copy of this famous gradual was one of the items displayed in Marquand’s most recent Open House in its Scribner Library temporary home.

Originally made for the convent of Marienbrunn (founded 1246), in Rulle near Osnabrück, this exquisitely illustrated manuscript carries the inscription: “The venerable and pious virgin Gisela von Kerssenbrock wrote, illuminated, notated, paginated, and decorated this admirable book with golden letters and beautiful images in her memory. In the year of our Lord 1300 her soul rested in peace.”

Though the inscription was added after Gisela’s death, and certainly exaggerated her all-encompassing role in the project, research has supported the claim that she made multiple contributions to the project, acting as one of the (possibly three) illuminators, with special responsibility for the writing and notation of the chants recorded in the Gradual. Also, from the evidence of the image above, she was also the cantrix – the leader of the choir, who would have gathered around the gradual used as the score for the musical component of church services in the convent. Since she was depicted and identified by name not once but twice in the illuminations, she was obviously a prominent and probably aristocratic member of the Cistercian convent, and may have commissioned the work. She is portrayed in acts of religious devotion – praying and singing – in two of the key scenes of the Christian calendar, the Nativity of Christ at Advent and the Resurrection of Christ at Easter, where Gisela (again, identified by name) is shown kneeling on the left outside the initial letter “R.” Both events were celebrated in special masses accompanied by music. Gisela’s pride in the value of her services to her faith and her community as an artist and musician here triumphs over the humility and self-effacement traditionally associated with cloistered religious women of her time.

Accompanying the full facsimile of the Gisela Codex is a commentary volume with essays about many aspects of art, music, and religious life in ca. 1300, as well as a CD: “Singen wie die Engel,” a recording of sacred music from the Gradual by the Frauenschola des Osnabrücker Jugendchores, directed by Clemens Breitschaft, recorded in the Herz-Jesu-Kirche, Osnabrück, on November 28, 2014.

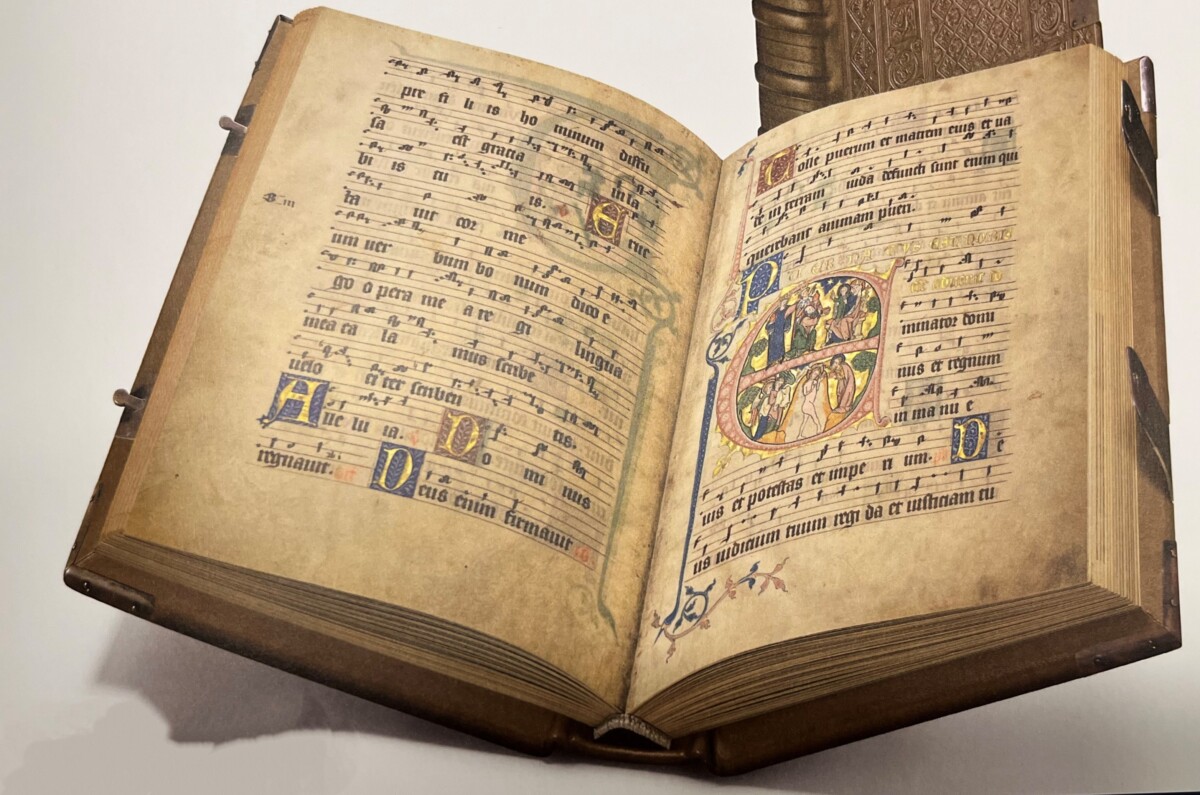

The unique and fragile nature of surviving illuminated manuscripts necessitates restricted use and careful handling of the originals to help preserve them for the future. High-quality facsimiles, created using current technological tools, come as close as possible to reproducing the look and feel of reading the unique books themselves, offering wider access to the original documents, and a welcome alternative to viewing online. Marquand Library is fortunate to have one of the most extensive collections in the United States of recent facsimiles of medieval and Renaissance illuminated manuscripts. These facsimiles provide an important resource for research and teaching and are frequently used in classes in many areas of study at Princeton University.

Nicola Shilliam, Western Art Bibliographer