Published between 1922 and 1926, Hakuyō is, historically speaking, one of Japan’s most important photography magazines. It was in this journal that the early 20th century artistic evolution from traditional Pictorialism to Modernist Expressionism was documented–inadvertently–with photographs and essays about photography by the most noteworthy Japanese photographers of the era. Although relatively few copies of Hakuyō survive, Marquand Library acquired 17 original issues, including a special edition catalog of an exhibition held in 1923.

Hakuyō was a monthly magazine published by the Japan Photographic Art Association [Nihon Kōga Geijutsu Kyōkai](JPAA)–the country’s first national organization with ‘art photography’ (geijutsu shashin) as its focus. Both the organization and the magazine were founded by photographer Fuchikami Hakuyō (1889-1960), who owned a photography studio in the city of Kobe. It is believed that the organization may have been formed with the idea of producing the first issue of Hakuyō in 1922, although most of the photographs we see here are by Fuchikami himself.

- (LEFT) Fuchikami Hakuyō, Foreigners in the Street at Noon [Hakuyō,Volume 1, No. 1 (1922)]. Typical of Fuchikami’s work before 1925, this photograph was taken in March of 1922 in the Kitano district of Kobe. It was an area of the city occupied by foreign residents, and is still famous today for its Western-style architecture.

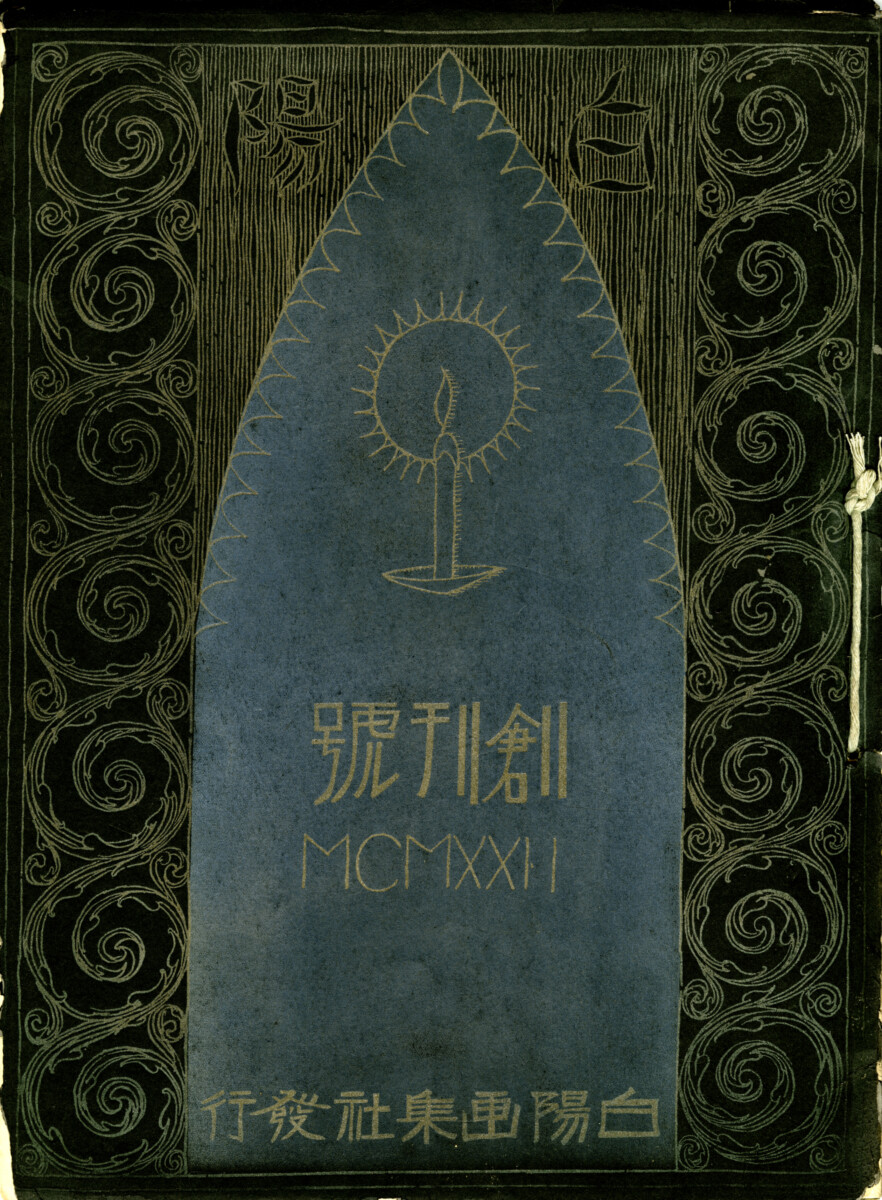

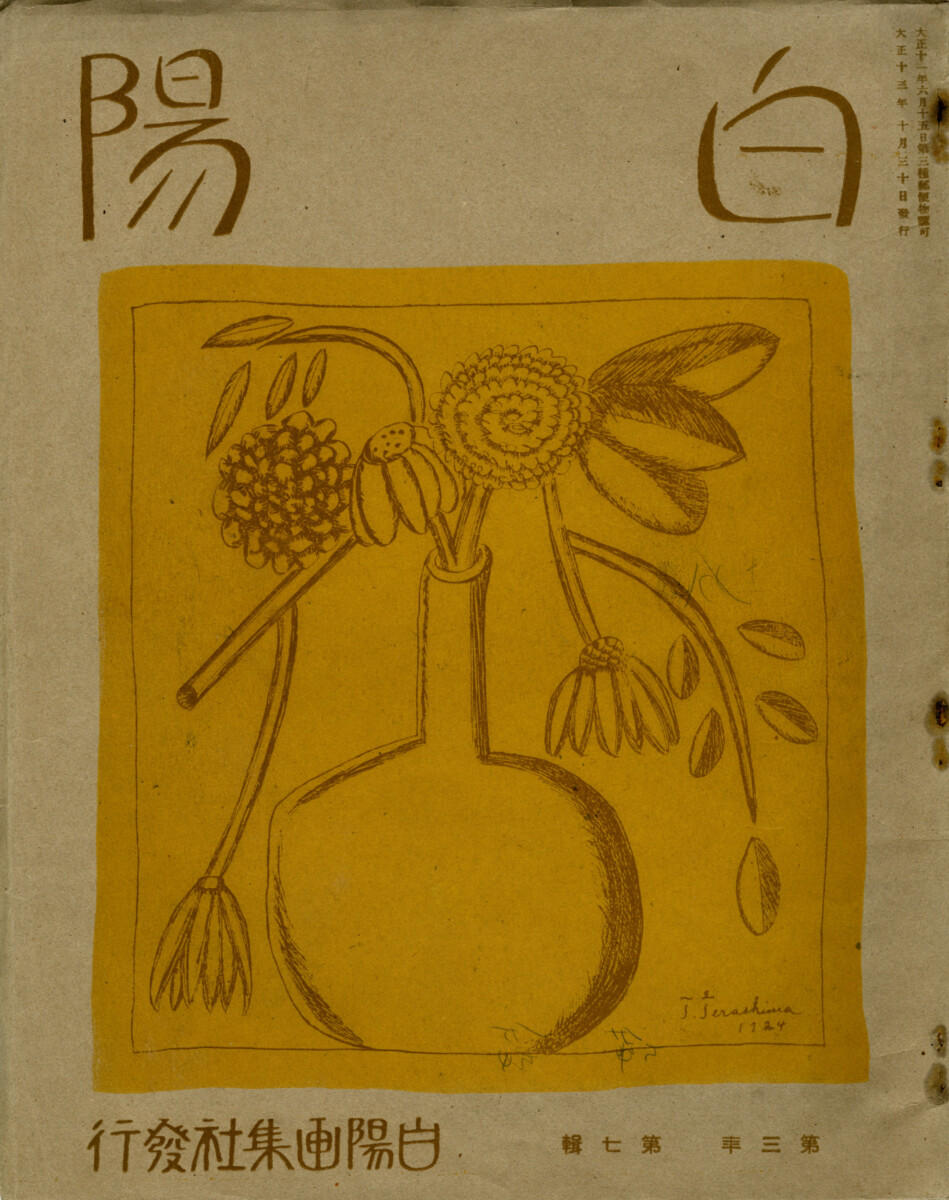

Marquand’s acquisition of a range of issues across five years allows us a more comprehensive sense of the development of Hakuyō than was previously possible. The early issues of the magazine, for example, were unique in size and shape. They had a variety modern “Western” images printed on their covers. In 1924, however, the dimensions of the magazine became uniform, and by 1926, the covers were all printed with an image of a European-looking woman embracing a guitar (see above) on differently colored stiff papers.

Cover of first issue, 1922

Volume 3, No. 7 (March, 1924)

Volume 4, No. 2 (February, 1925)

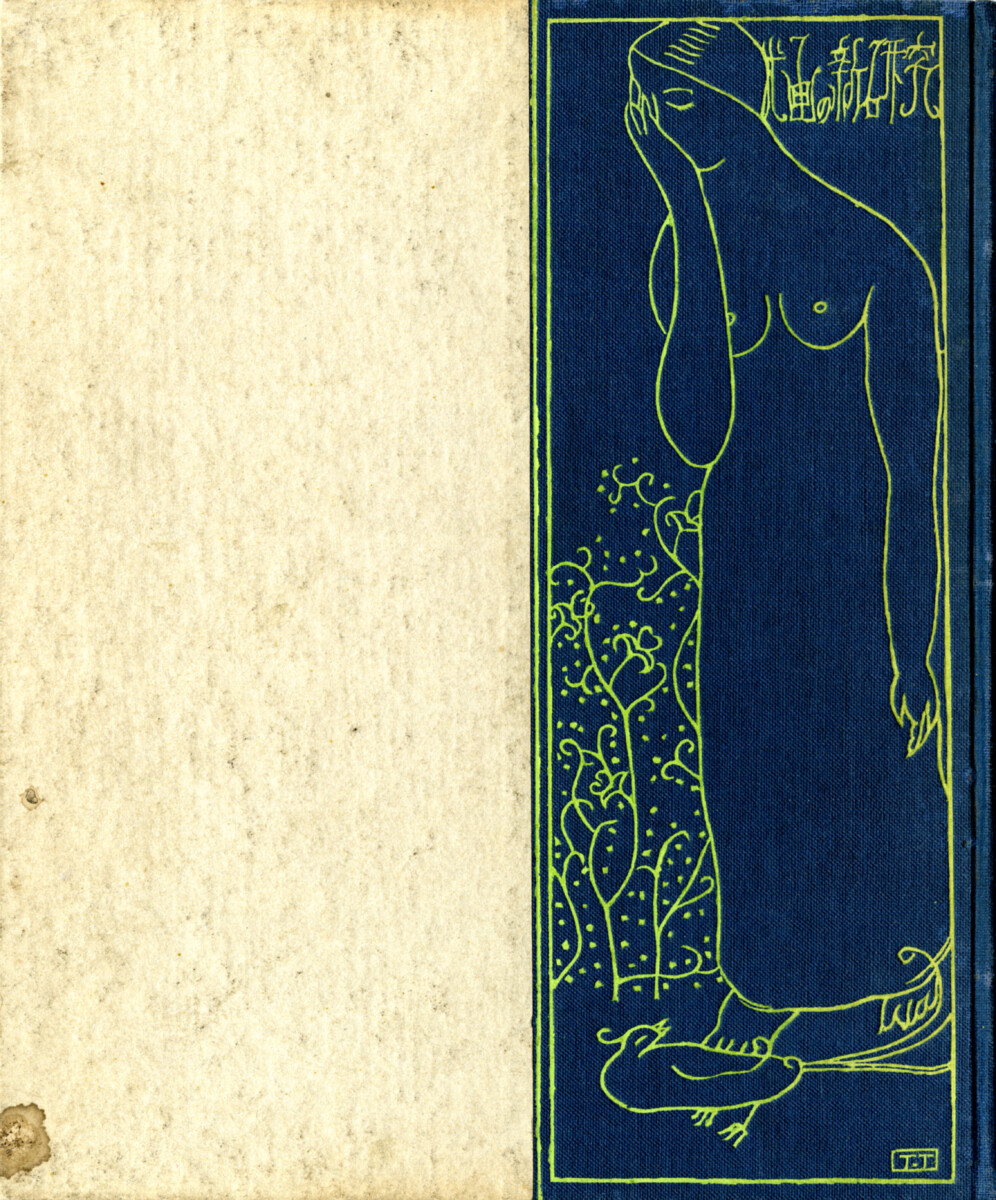

No matter what the year, every aspect of this publication was beautifully designed with woodblock prints on the front and back covers and decorative flourishes added to pages of the text.[1] Each issue was filled with finely printed photographs: individual collotypes that had been tipped in and could presumably be removed for display.

Back cover design (1923)

Back cover design (1925)

In the early part of the 20th-century, Japanese photographers were greatly influenced by Western photography, and particularly by Western Pictorialism–an aesthetic movement that had begun in Europe at the end of the nineteenth century. Pictorialists eschewed the documentary aspect of photography and attempted to make their photographs appear more like paintings. Like other fine artists in Japan, Fuchikami and his fellow art photographers also rejected being identified as “professional artists,” with its commercial connotations, and referred to themselves as “advanced amateurs.”

Their portraits and images of nature were conceived in half tones and with a soft focus. Efforts were also made to enhance the texture of photographs to give them a painterly feel. This visual link between painting and photography was especially appealing to Japanese photographers who were struggling to elevate photography to a fine art in early 20th-century Japan.

Fuchikami Hakuyō, Old Man [Hakuyō, Volume 1, No. 1 (1922)]

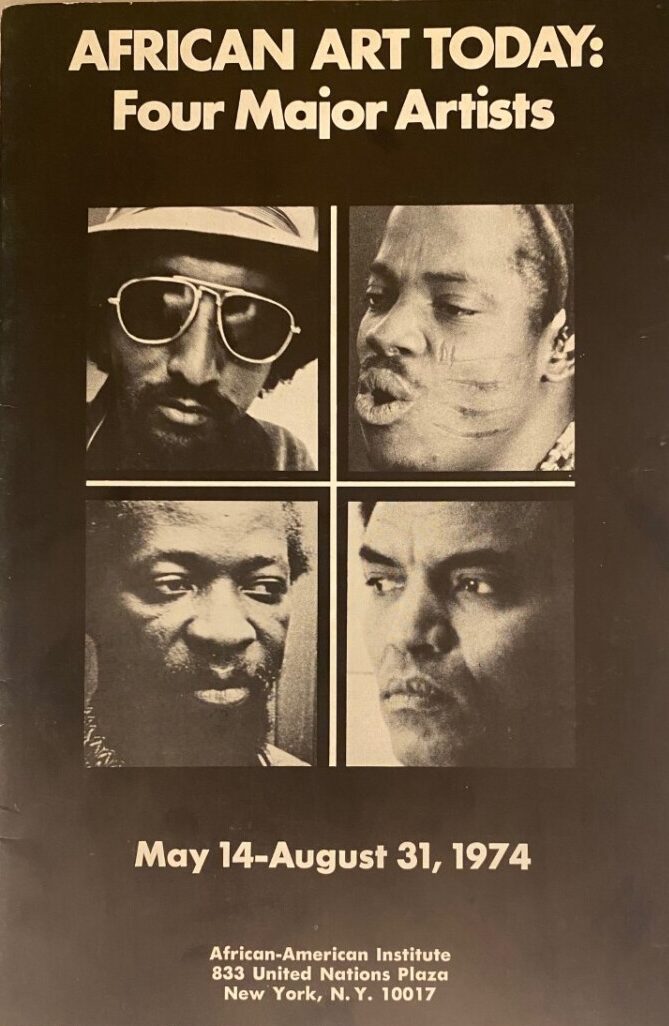

Cover of 1923 exhibition catalog, Koga no shin-kenkyū [New Studies in Photography], published as a special issue of Hakuyō (November 1923).

We see these photographers embracing the Pictorialist style in earlier issues of the magazine and in the Japan Photographic Art Association‘s 1923 group exhibition catalog, Koga no shin-kenkyū [New Studies in Photography]. Published as a special issue of Hakuyō in November 1923, the catalog was sponsored by the newspaper publishing company, Osaka Mainichi Shinbunsha.

Takada Minayoshi (1899-1982), Departing Boats. Though his work was rooted in the Pictorialist-style seen in this 1923 photograph, Takada later became one of the leading proponents of Constructivism. From the exhibition catalog Koga no shin-kenkyū [New Studies in Photography].

Kagiyama Ichirō (active 1906-after 1941), Lake (Marsh). As seen here, simulating the texture of paintings was an important aspect of Japanese Pictorialism. Not much is known about the “amateur” work of Kagiyama, who spent over 30 years in Australia as commercial photographer to the Japanese community living there. From the exhibition catalog Koga no shin-kenkyū [New Studies in Photography].

By 1925, the images that appeared in Hakuyō were very different. The photography of the JPAA had been transformed into a new kind of modernist expressionism influenced by Western Constructivism and the changing urban environment. Surprisingly, this was not a casual development over time, but a twist of fate caused by a natural disaster.

Fuchikami Hakuyō, Circle and Human Body [Hakuyō, Volume 5, No. 6 (1926)] Hakuyō favored manufactured motifs like this one in his Constructivist works.

The Great Kanto earthquake, which devastated Japan’s capital city of Tokyo in 1923, forced the relocation of artists of the MAVO group to western Japan. Heavily influenced by European avant-garde movements like Futurism, Dadaism, and Constructivism, MAVO spearheaded new art movements in Japan. Now, newly settled in the Kobe area, the MAVO group members encountered Fuchikami Hakyuyo and the JPAA. Their exchange of ideas resulted in the birth of the Japanese Constructivist School (kōsei-ha).

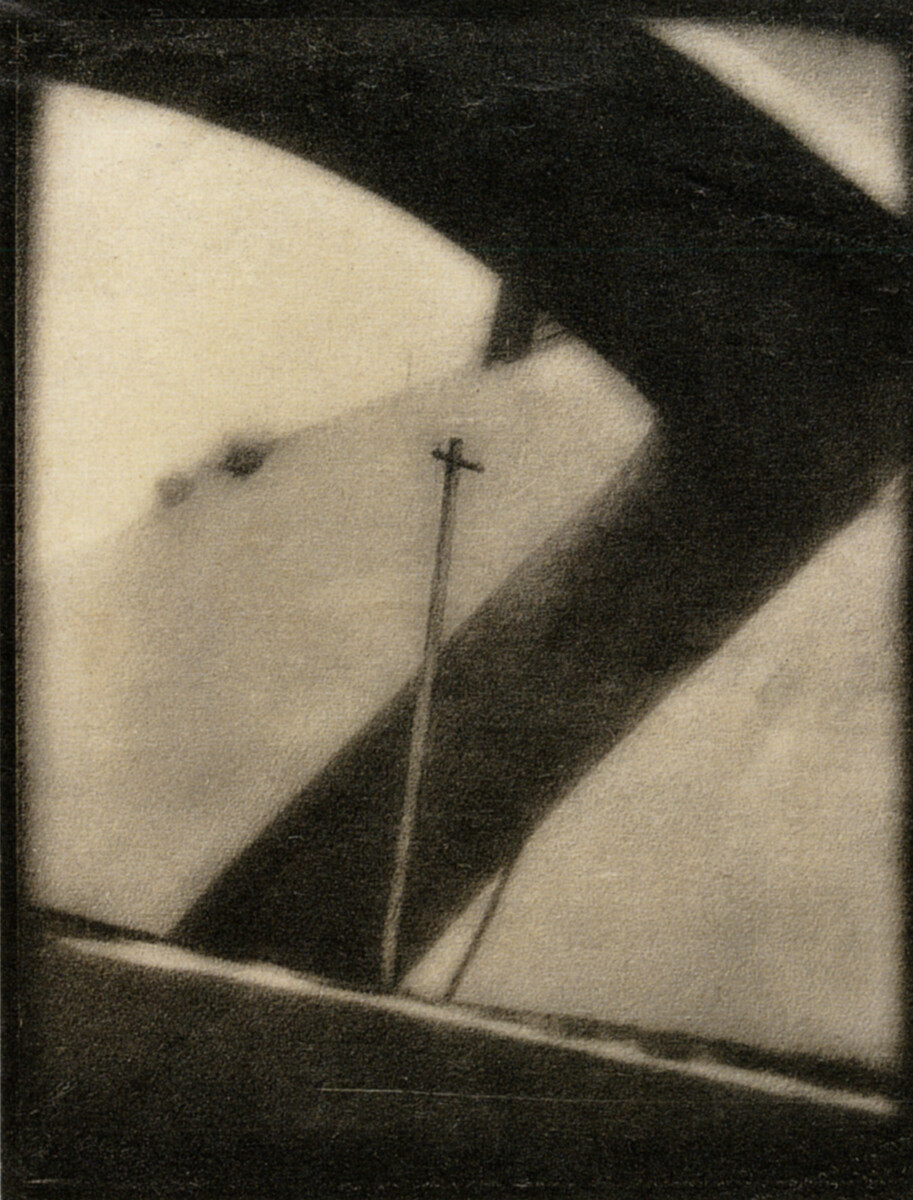

The pages of Hakuyō clearly document the transformation that took place in photography over the next few years. We see there is a breaking away from the conventional subjects of Pictorialism and a movement toward more abstract notions of beauty found in manufactured motifs and urban landscapes. By 1925, the artist essays that accompany the pictures describe the photograph as a work of abstract art. Fuchikami himself, in an article entitled “Impressions, Still Lifes” (Kansō seibutsu) in a 1925 issue of Hakuyō, [vol. 4, no. 1] declares that “[t]he ultimate reason for viewing nature is to discover the emotive qualities of abstracted nature.”

Matsuo Saigorō (1905-1956) Study # 1 [Hakuyō, Volume 5, No. 6 (1926)] The urban landscape was a popular Constructivist theme.

Constructivist photography reached its peak in 1925, driven by Fuchikami and other photographers like Tsusaka Jun, Matsuo Saigorō, Takada Minyoshi, and Kara Takeshi.

(RIGHT) Tsusaka Jun (1900-1963), Bridge. [Hakuyō, Volume 5, No. 6 (1926)] Tsusaka Jun was one of the JPAA’s first members in 1923. He learned photography while working in the Kobe shipyards and at an aircraft manufacturing plant in Nagoya. Like other members of the association, his early work featured traditional subject matter photographed in soft focus. In 1925, however, inspired by Fuchikami, Tsusaka joined the Constructivist School movement and broke away from nature studies and portraits to become one of Japan’s most famous avant-garde photographers. In this photograph, considered a hallmark of Constructionism, Tsusaka treats his subject matter—an urban landscape—as an abstract construction.

Scholars speculate, however, that in 1926, Fuchikami began to distance himself from Constructivism, and in September of that year, he ceased production of Hakuyō. Even so, as Anne Wilkes Tucker has observed in The History of Japanese Photography, these Constructivist photographers “charted the route toward modernism” in Japanese photography.

Despite the ephemeral nature of the magazine in general and the transience of old photographs, we are fortunate that these issues of Hakuyō have survived to document 1920’s Japanese photography and its first steps toward modernism.

- [1] These images were in keeping with a new movement in Japanese woodblock printing: The Creative Print Movement (Sōsaku–hanga). In emulation of Western printmaking, these artists shunned traditional Japanese printmaking to carve their own blocks and create “art for art’s sake.”

- Nicole Fabricand-Person, Japanese Art Specialist