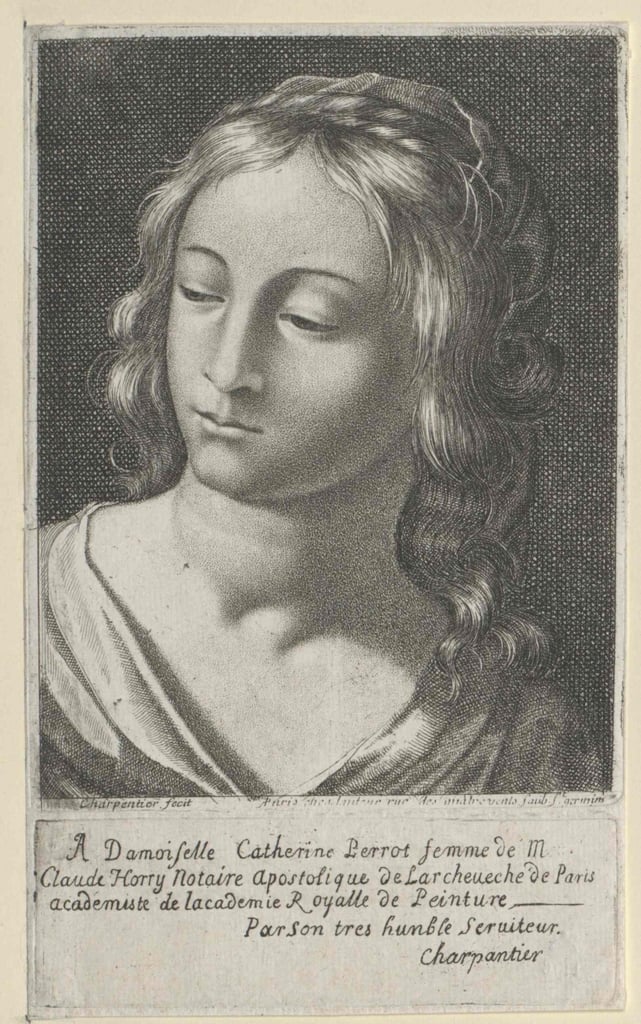

The Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, created in 1648 during the Regency of Anne of Austria, shaped the teaching and regulation of the arts of painting and sculpture in France. During the 145 years of its existence, only fifteen women were elected to its membership. Catherine Perrot (ca. 1653- after 1693?), only the seventh female member to be accepted into its ranks in 1682, was the first French woman to publish a treatise on painting. Her Traité de la mignature: dedié à Madame la Princesse de Guimené / par Mademoiselle Perrot, de l’Académie Roïale (Paris: chez Arnoult Seneuze, Marchand Libraire rue de la Harpe… 1693), a recent acquisition by Marquand Library, is one of possibly only eight copies recorded in American institutional collections. But what made this acquisition even more exciting was the description offered by the dealer, which provided information to support a birth date for the artist/author of ca. 1653, more than 30 years later then has traditionally been suggested. So little is still known about Perrot’s life, that this new date leads to a reassessment of her life and career. Even the whereabouts of this portrait of the artist by Charpentier is unknown and is reproduced here from L’Art: revue bimensuelle illustrée (1888).

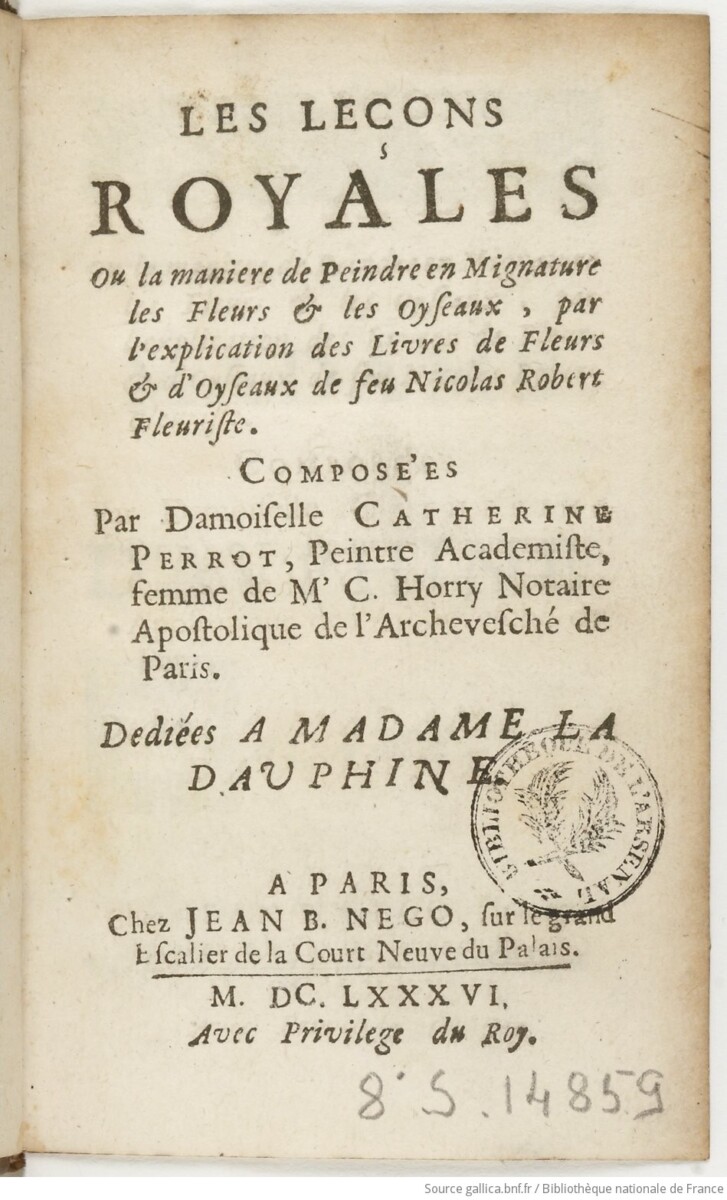

Perrot’s Traité de la mignature originated from her experiences teaching painting to royal princesses and aristocratic women at the French court, including Marie-Louise d’Orléans (1662-1689), the Dauphine, Louis XIV’s niece. The text developed from Perrot’s earlier publication, Leçons royales: ou la manière de peindre en mignature les fleurs et les oyseaux; par l’explication des livres de fleurs et d’oyseaux de feu Nicolas Robert, fleuriste (1686), dedicated to her most famous pupil, the Dauphine, who later became Queen of Spain through her marriage to King Charles II of Spain in 1679. In her portrait above, the Dauphine gestures towards the delicate flowers and swans in the background, the type of subject matter she might herself have painted.

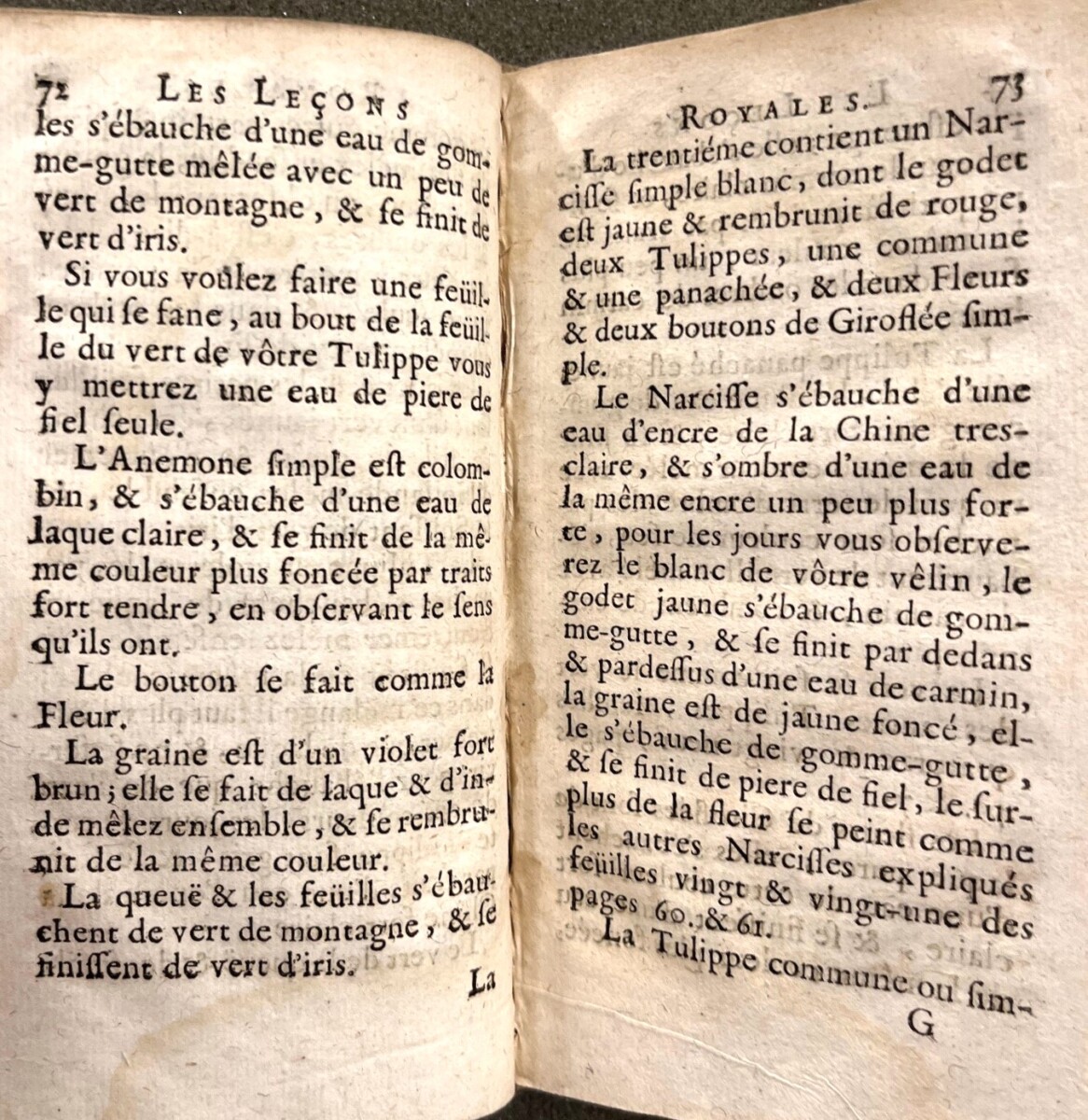

Perrot had trained with Nicolas Robert (1614-1685), whose exquisite botanical and ornithological watercolors on vellum were painted first for Gaston d’Orléans and then for Louis XIV, after examples found in the Jardin des Plantes and the Royal Ménagerie. While Robert’s vellums were highly esteemed by the King, his prints of the same subjects were also popular and often served as models for amateur painters. A watercolor of a pot of flowers placed on a mirror was Catherine’s Perrot’s entry piece for admission to the Académie. Perrot’s publications were attractive to her primarily female audience: they offered helpful information on the subject of miniature painting for beginners who wished to learn more about the practice without a tutor. These compact volumes, small enough to be carried around by their owner, also supplied practical recipes for creating colors for those skilled enough to create miniatures themselves or others who wished only to add appropriate color to traced drawings or prints for their own pleasure. As shown in the images above, the text made close reference to examples of the numbered plates found in two books of Robert’s prints, Diverse fleurs dessinées et gravées d’apres la nature (1660) and Diverses Oyseaux (1673).

On the title page to the Leçons (1686), Perrot had been careful to include her credentials: the association with the books of Nicolas Robert, her membership of the Académie, her dedication to her former pupil the Dauphine, and her marriage to Claude Horry. Horry held an important bureaucratic office — apostolic notary to the Archbishop of Paris, a position whose power was extended by order of Louis XIV in 1691 to “notaire royaux et apostolique.” He had also authored several legislative books, including Le Parfait Notaire Apostolique (1688) and Le Pratique Civile des Officialitez Ordinaires… (1703), noted here because we learn from that title page that his home (and more importantly, presumably that of Catherine, if still living) was in “rue neuve Notre-Dame, devant la grande Porte de l’Eglise & Paroisse de Sainte Geneviève du miracle des Ardens,” Paris.

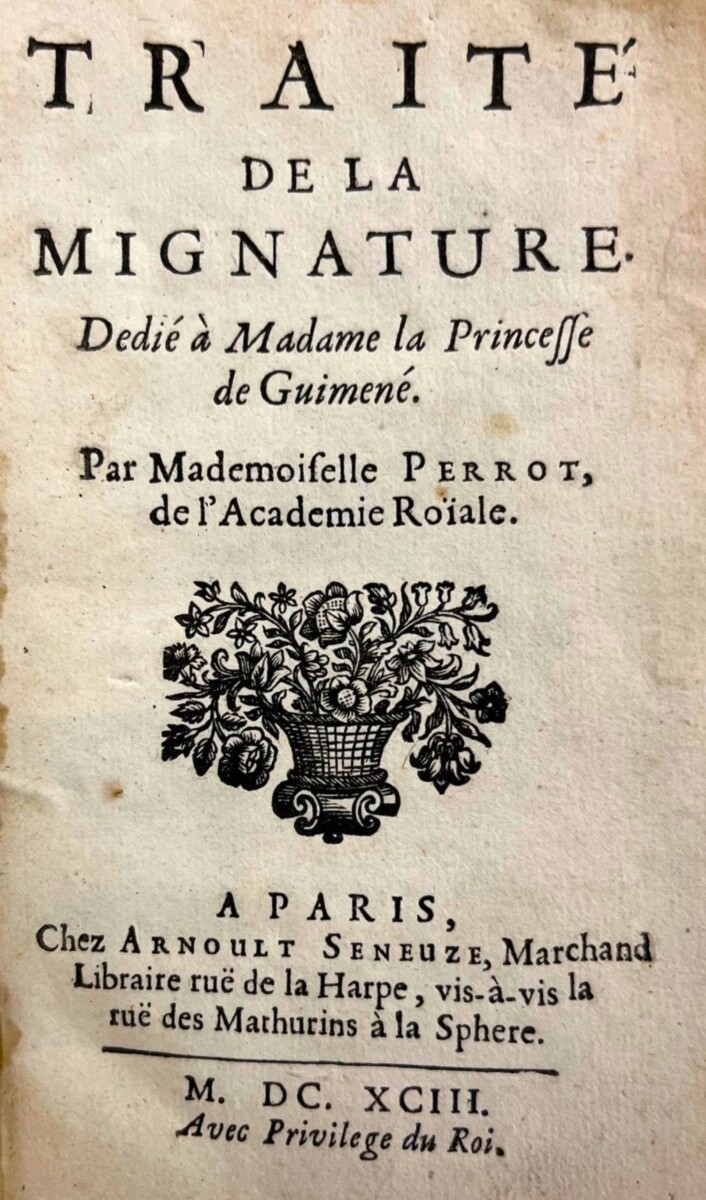

By the time that Perrot reworked her 1686 publication and published it as the Traité (1693) there were notable changes. The title announces a scholarly work, befitting an established académicienne, who no longer needed to be identified by her husband’s status. Following the death of Dauphine/Queen of Spain in 1689, a new dedicatee was needed, this time to “Madame la Princesse de Guimené,” another pupil. In the brief “Avis,” Perrot also now reminds her readers that she had been appointed to the Académie by the venerable Monsieur Le Brun himself (who had died in 1690), and that she was the pupil of Nicolas Robert, the Royal flower painter.

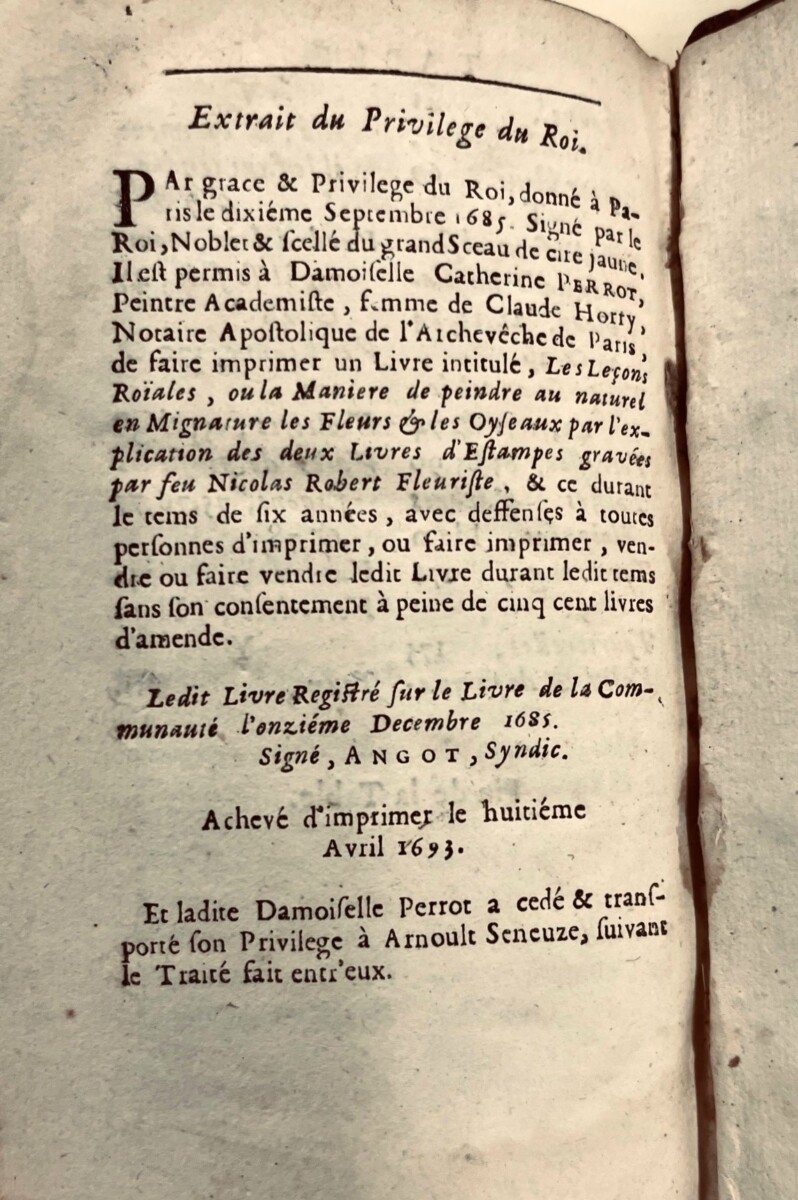

From the privilege page at the end of the Traité (printed in April 1693), we learn that the publishing rights to the 1685 Leçons, good for 6 years, had been transferred legally to Arnoult Seneuze, the new publisher. A few months after the publication of the Traité, Perrot was summoned to appear before the Académie. Somewhat mysteriously, nothing further is heard of Mademoiselle Catherine Perrot after this date, and with no other recorded information in the minutes of the Académie, it has been assumed that she either withdrew or was expelled from the membership. We can only speculate on whether her Traité may have ruffled feathers at the Académie. Did she offend by introducing a few added remarks on the theory of painting in general, which have been shown to derive from the work of illustrious theoreticians, such as Roger de Piles and Roland Fréart de Chambray, without acknowledgement (today = plagiarism; then = commonplace)? Or was it because the author had ventured beyond her supposed area of expertise — miniature painting, considered low in the hierarchy of subject matter — into the loftier realms of history painting (figures) and landscape, by adding recipes for painting flesh, draperies, sky and land? Or was it simply that she was a female author/artist attempting to assert her voice in a predominantly male field in a book that some would have considered too lightweight, written for amateurs not professional artists. Perrot’s book may also have been compared to the only other work on the topic: the (originally anonymous) Ecole de mignature or Traité de mignature published by “C.B” (generally attributed to Claude Boutet, though first published by Christophe Ballard). While Boutet’s treatise, first published ca. 1673, appeared in many later different editions and translations (seven in English alone between 1739 and 1752), Perrot’s Traité only reappeared in 1725 as part of Felibien’s Entretiens sur les vies et sur les ouvrages des plus excellents peintres anciens et modernes, tacked on to the very end on the last volume of the series.

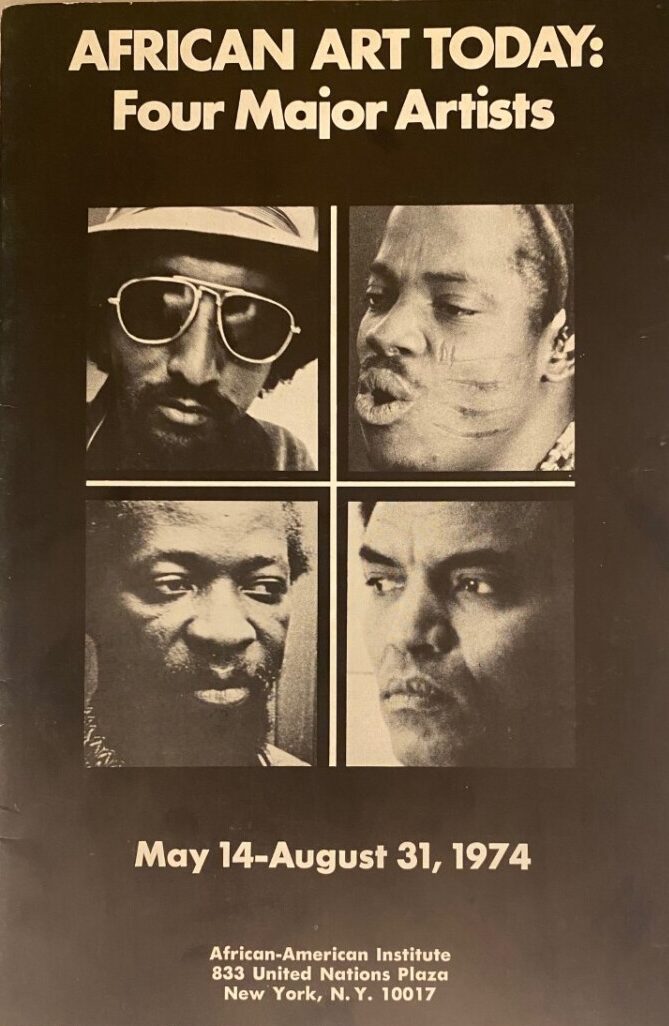

After Perrot’s admission in 1682, no more women were admitted to the Académie until 1720. In 1706, it (temporarily) ended the admission of women: seven women in a membership of more than 100 men appears to have been considered somewhat “dangerous.” The publication that same year of Elisabeth Sophie Chéron’s Livre a dessiner, composé de testes tirées des plus beaux ouvrages de Raphaël (1706), may have confirmed fears that an increased female membership might lead to more problems with women artists aspiring to greater power. Chéron (1648-1711), one of the other six female academy members in Perrot’s cohort and a respected portrait painter and more outspoken proto-feminist, has been contrasted by several authors with the “aged” and less threatening Perrot. All previous authors appear to have appraised Perrot’s career from the perspective of a tentative birthdate of ca. 1620, making her in her sixties when elected to the Académie in 1682. This presumed age, coupled with her advancement through royal preferment, led one author to use the phrase “[une] dame âgée inoffensive” to describe her.1

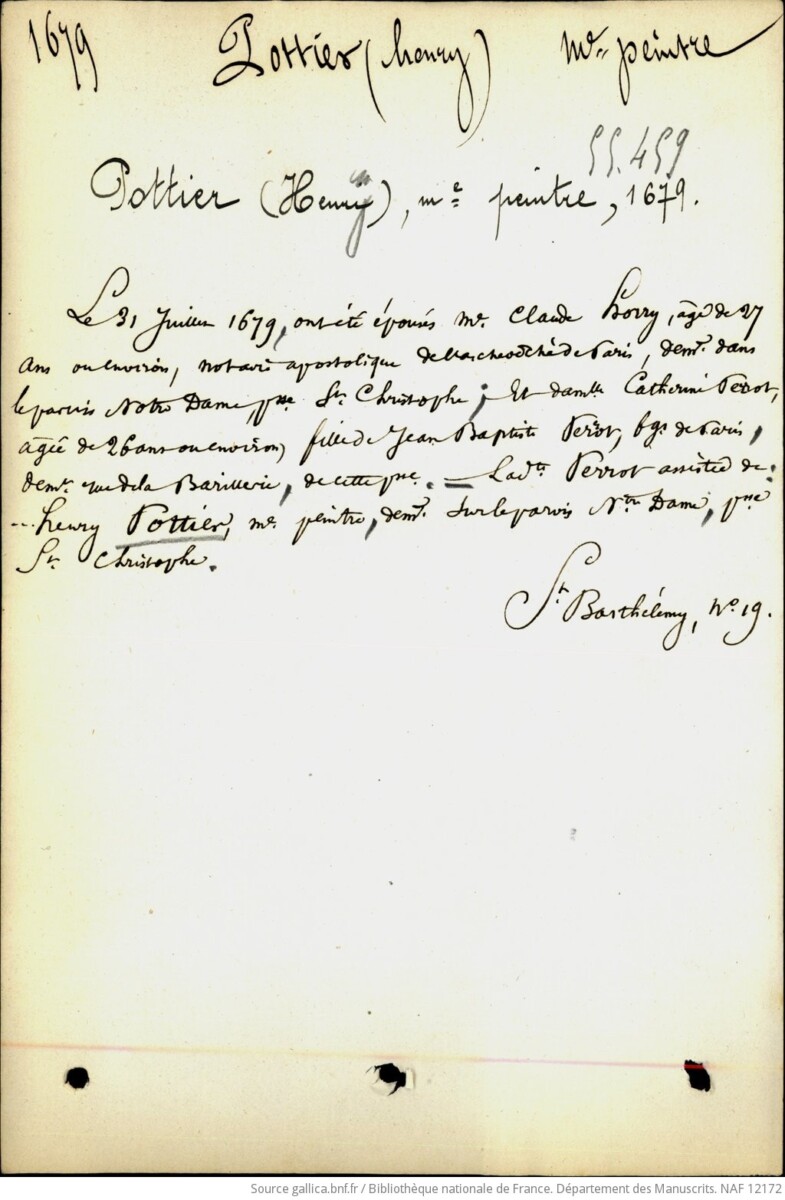

However, the new information regarding Perrot’s age that accompanied Marquand’s copy of the Traité changes our view of Perrot’s career. Many thanks are due to Stéphanie Guerit for bringing to light a manuscript record of the marriage of Catherine Perrot to Claude Horry on June 31, 1679. Catherine is described as being about 26 years old, daughter of Jean Baptiste Perrot, living at rue de la Barillerie, and Henry Pottier “master painter” is recorded as “assisting” Perrot. This information has long been available in the records of the civil status of French artists and artisans compiled by Léon de Laborde (1807-1869), director of the Imperial Archives, but was not widely available until it was digitized as the Répertoire alphabétique de noms d’artistes et artisans, des XVIe, XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles, relevés dans les anciens registres de l’État civil parisien par le marquis Léon de Laborde, dit “Fichier Laborde.” Stéphanie Guerit also cited another source in support of this new view of Perrot’s age: a note relating to Claude Horry in a publication of 1703 recording official permission to delay the baptism of Charles Horry, born in 1689, described as the son of Catherine Perrot and Claude Horry. I was able to explore these sources for myself, and they led to more discoveries.

When she edited and republished the 1686 Leçons as the Traité in 1693, instead of being in her sixties and presumably nearing the end of her career, if not her life (some scholars have suggested that this work may have been published posthumously), Perrot would have been a seasoned but far from elderly académicienne. It is heartening that it still remains possible to discover documents that radically change accepted narratives about the work of women and other underrepresented artists. More research of digitized archival records and other sources may bring news of what actually happened to Catherine Perrot after 1693.

- Elisabeth Lavezzi, “Catherine Perrot, peintre savant en miniature: Les Leçons Royales de 1686 et de 1693.” In Colette Nativel, ed. Femmes savantes, savoirs des femmes du crépuscule de la Renaissance a l’aube des Lumières. Geneva: Droz, 1999, p. 230.