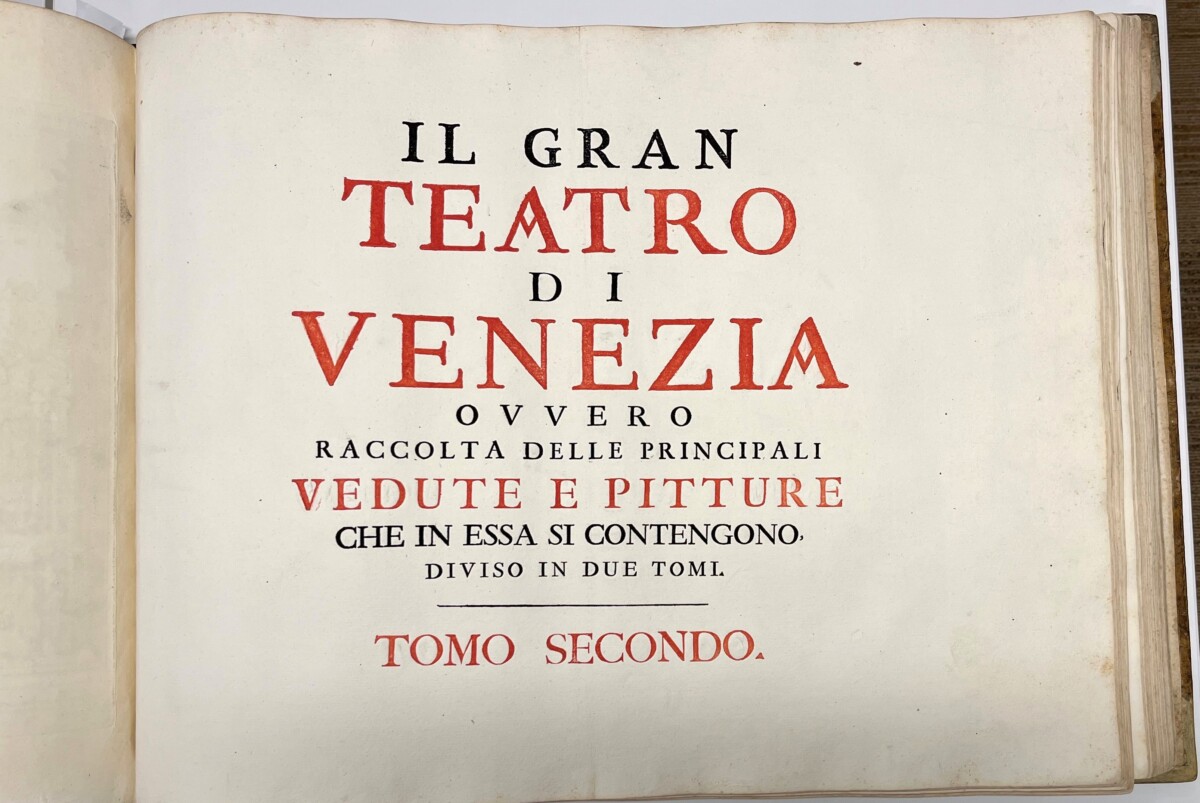

Although summer has (almost) officially ended, and many of us have returned to work, it’s always possible to take a virtual trip with one of Marquand’s rare topographical books, such as Il Gran Teatro di Venezia overro raccolta delle principali vedute e pitture che in essa si contengono, a recent acquisition. Venice, still miraculously shimmering on its lagoon in the Adriatic, in spite of the ravages of time, too many admirers, and the recent consequences of global warming, is brought vividly to life in this publication from the early eighteenth century.

Il Gran Teatro consists of two albums of prints published in one large volume: part one of Marquand’s copy offers 65 views of the churches, confraternities, palaces, academies, and other notable architecture in their picturesque settings; part two shows 57 printed reproductions of major works of art to be seen inside Venetian institutions, including many paintings in the chambers of the Palazzo Ducale, the Scuole Grandi di San Marco and San Rocco, and churches such as Santa Maria della Salute and SS. Giovanni e Paolo, among others. This book would have provided either a lavish memento of an actual visit or the eighteenth-century version of what we would now consider a virtual tour of the city, illustrated with many of its famous views as well as highlights of paintings in the collections of civic art, for someone who had not been able to make the Grand Tour in ca. 1720.

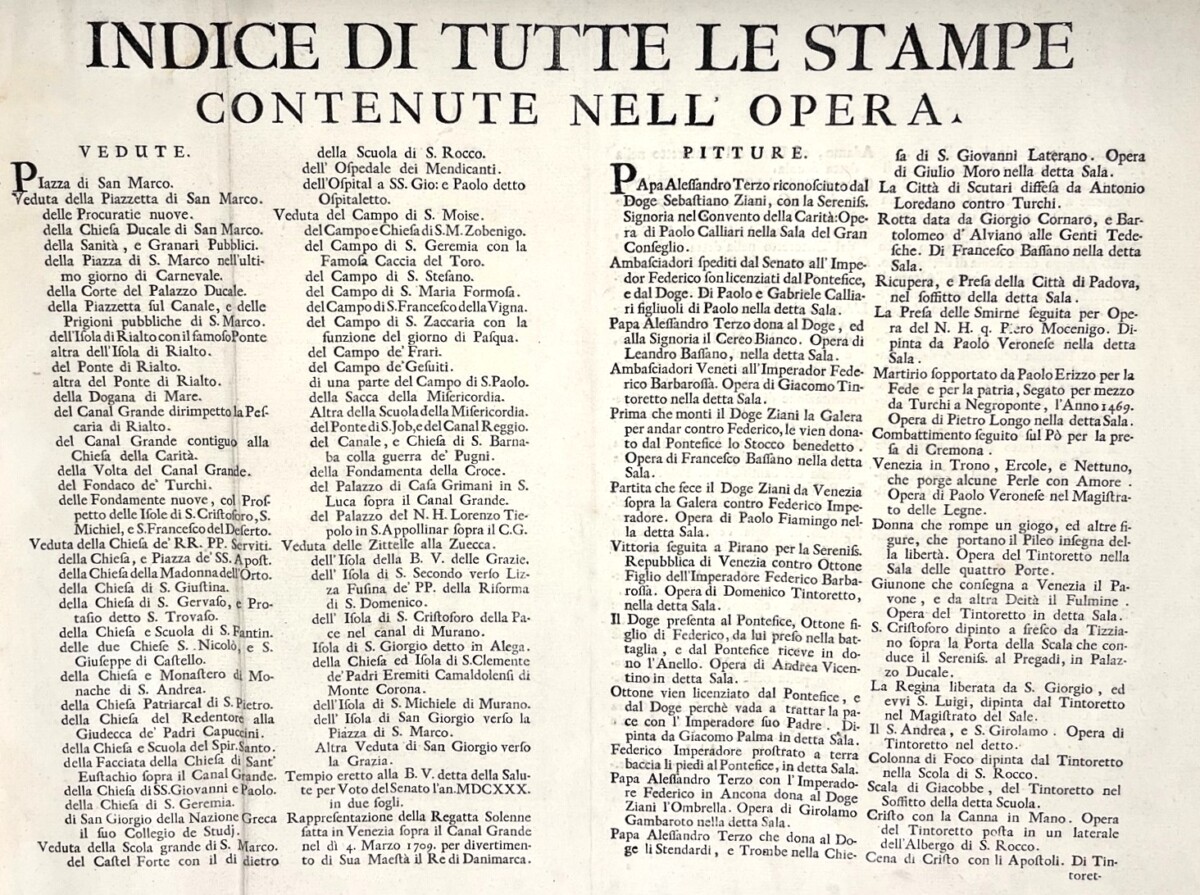

The publication of a high quality, large format book with so many views of Venice and its art works was both an act of civic pride as well as an economic and cultural statement for the Republic. Though still a Mediterranean entrepot that attracted many visitors, the political power of Venice had waned by this date. Funded by Battista Nicolosi and other members of the Venetian elite, an academy was created to collect material for the proposed publication, which took as its model two earlier view books, Le Fabbriche e Vedute di Venezia (1703) by Luca Carlevarijs and Le Singolarita di Venezia (1708-1709) by Vincenzo Coronelli. The ambitious project took many years to come to fruition and was finally handed to the publisher Domenico Lovisa (1690-1750) to execute as the Gran Teatro, first printed as a collection of prints with no title page in an undated “edition” [ca. 1717]. Marquand’s copy, also with an undated title page but with the addition of a very useful two-page index (see first page, below), is thought to date from that period. Another version, with a slightly different title was printed in 1720. Later versions (1730s-1750s) are distinguished by the inscription “Appo T. Viero Venezia” added to the plates.

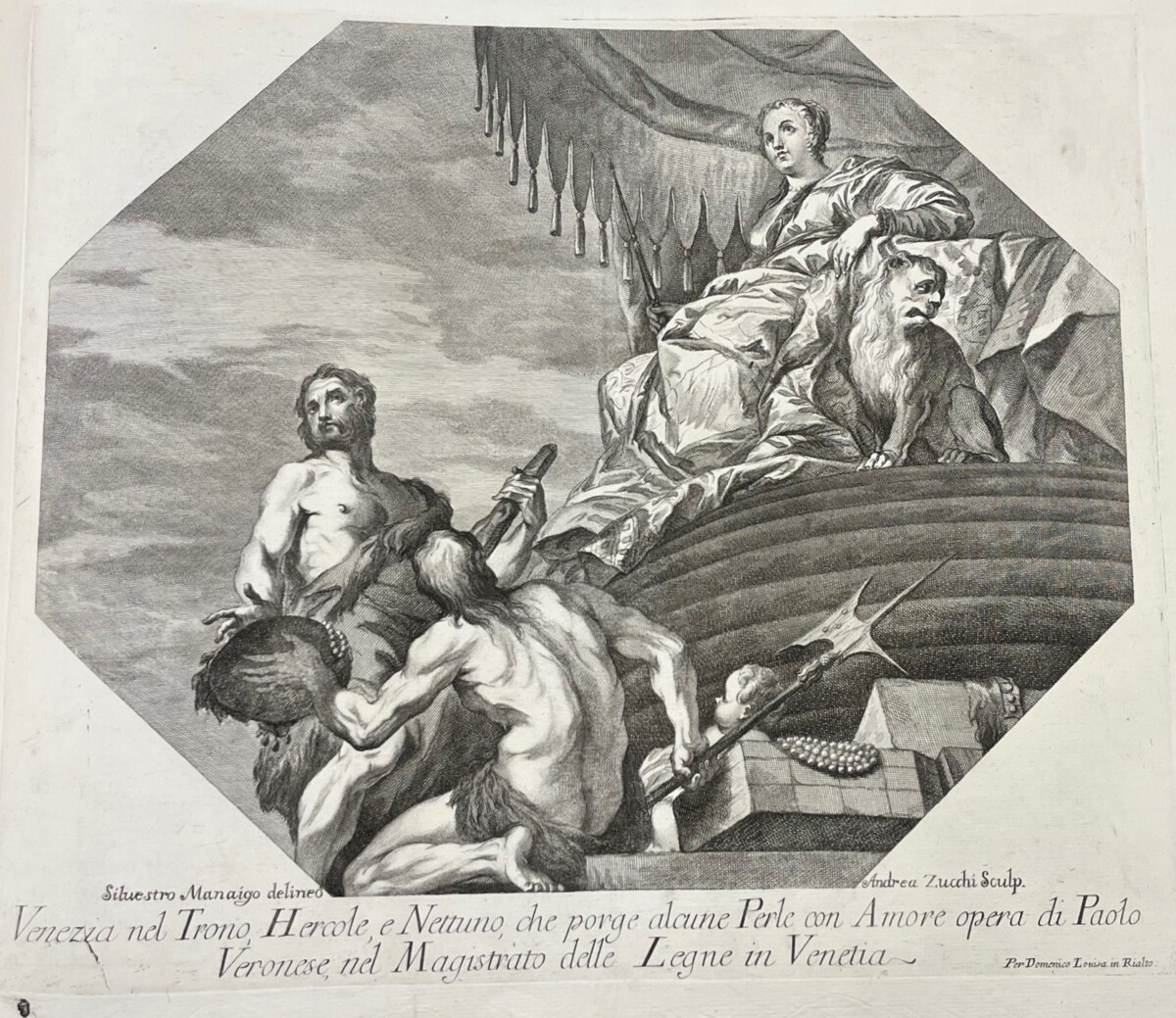

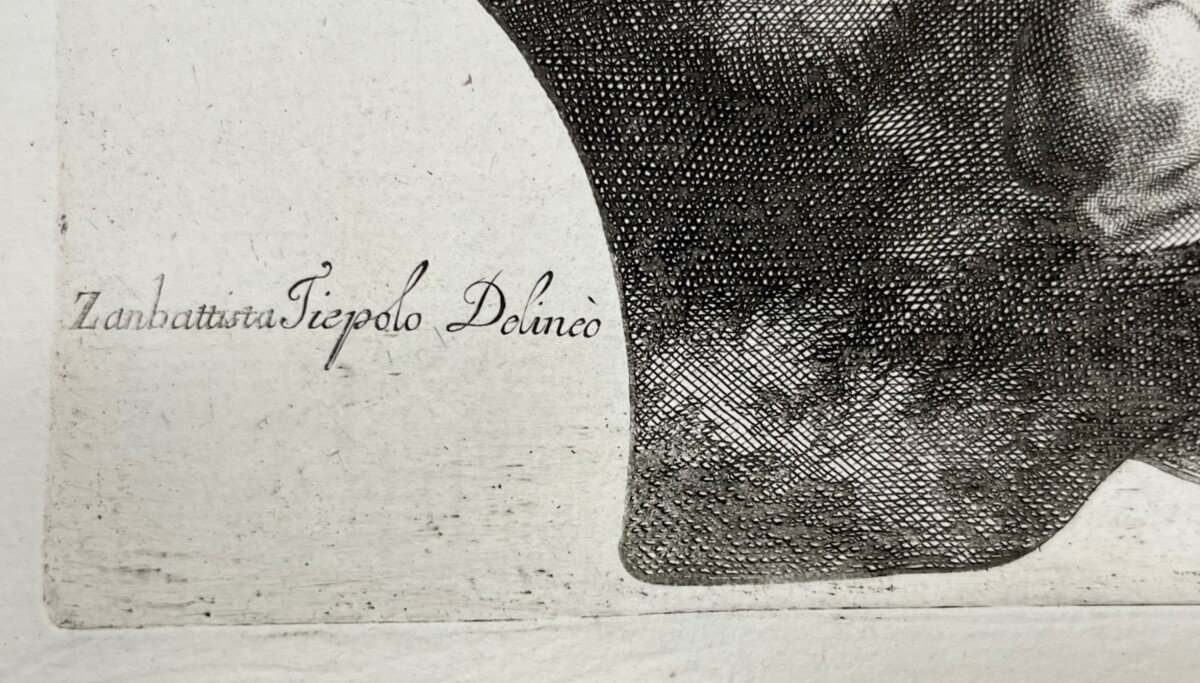

With its long tradition of book publishing, patrician funding, and the presence of a large community of painters and engravers, Venice provided Lovisa with the means to complete the project. Many successful artists worked on the prints, including Andrea Zucchi, Luca Carlevarijs, Giuseppe Valeriani, Felippo Vasconi, Domenico Rossetti, Silvestro Manaigo, and a young Giambattista Tiepolo (above: his signature in one of the plates), though many are also unsigned.

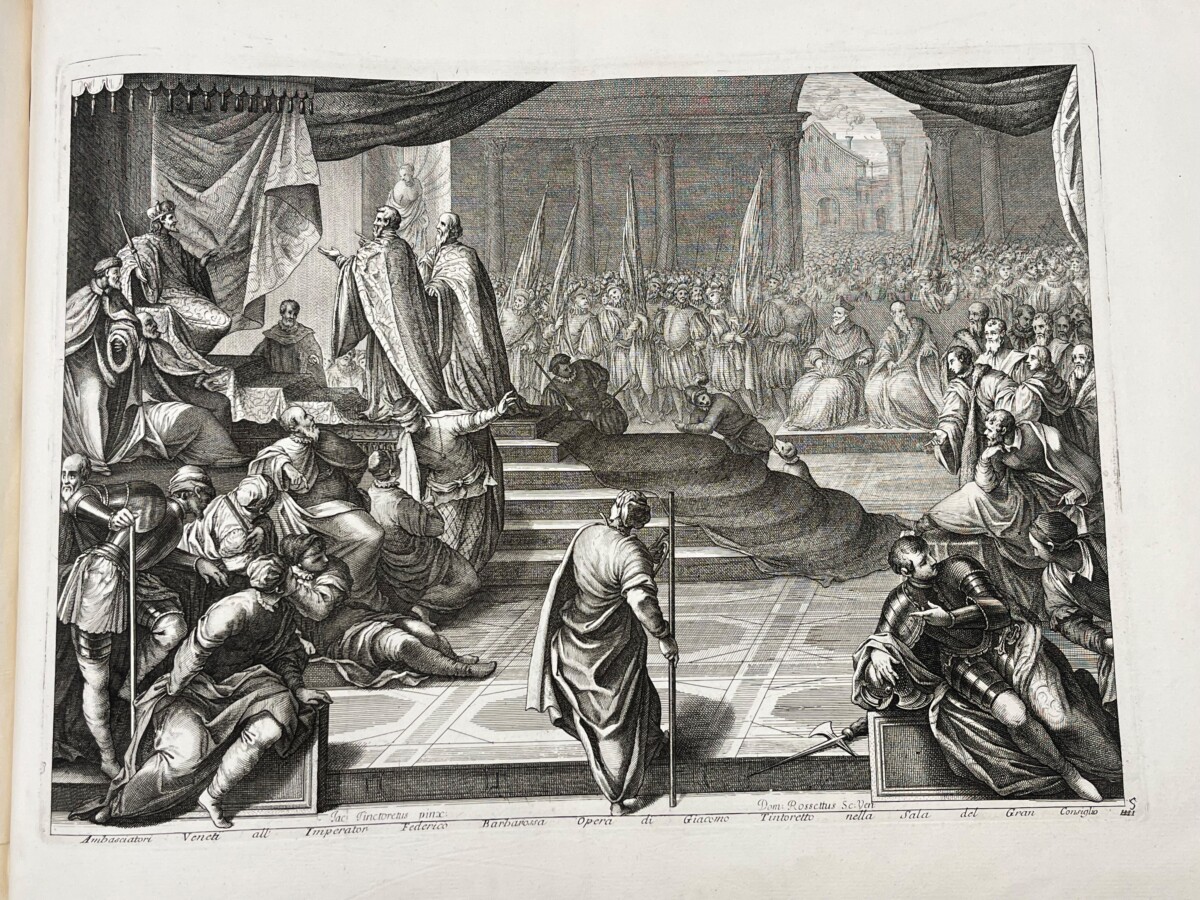

The prints in the second part of the book are interesting examples of early reproductions of works of art in public collections. Many of the paintings are depictions of events in the history of the Serenissima by some of the foremost Venetian artists working in the sixteenth century, including Veronese, Tintoretto, and Palma il Giovane. This print after Tintoretto’s painting in the Chamber of the Great Council of Doge’s Palace shows the reception of the Venetian ambassadors at the court of Frederick I Barbarossa (Holy Roman Emperor, 1155-1190), a period when Venice was a major power in the Mediterranean.

Another print, made by Andrea Zucchi after a drawing by Silvestro Manaigo, reproduces Tintoretto’s dramatic painting (ca. 1562-1566) of the miraculous “translation” (or theft, depending on your point of view), of the remains of St. Mark from Alexandria to Venice in the ninth century. Its subject would have been particularly challenging for the printmakers: a night scene, with sudden lightning and the illusion of ghostly figures and cherubim in the background, contrasting with the dramatically lit, realistic flesh of the protagonists in the foreground. Venerated as the patron saint of the city, images of St. Mark were a major feature of the Scuola Grande di San Marco. This painting is now in the collection of the Accademia, Venice.

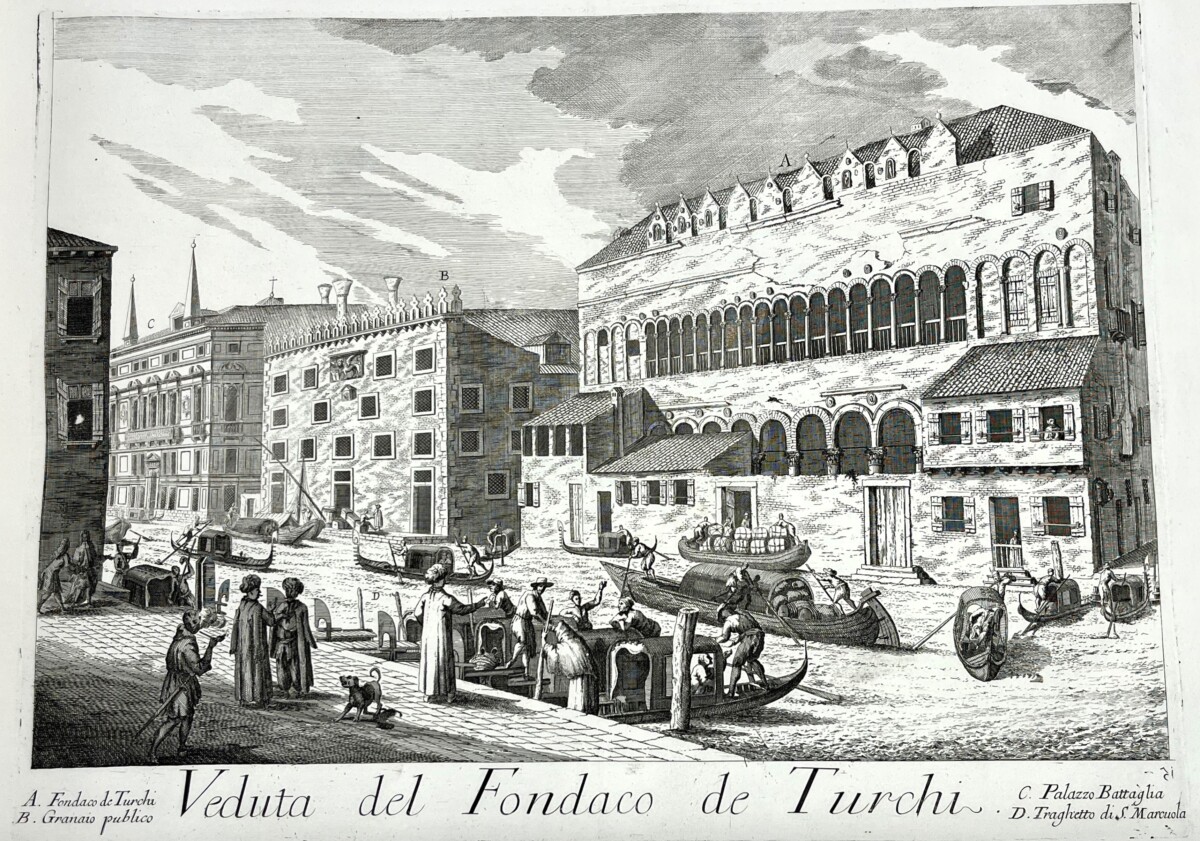

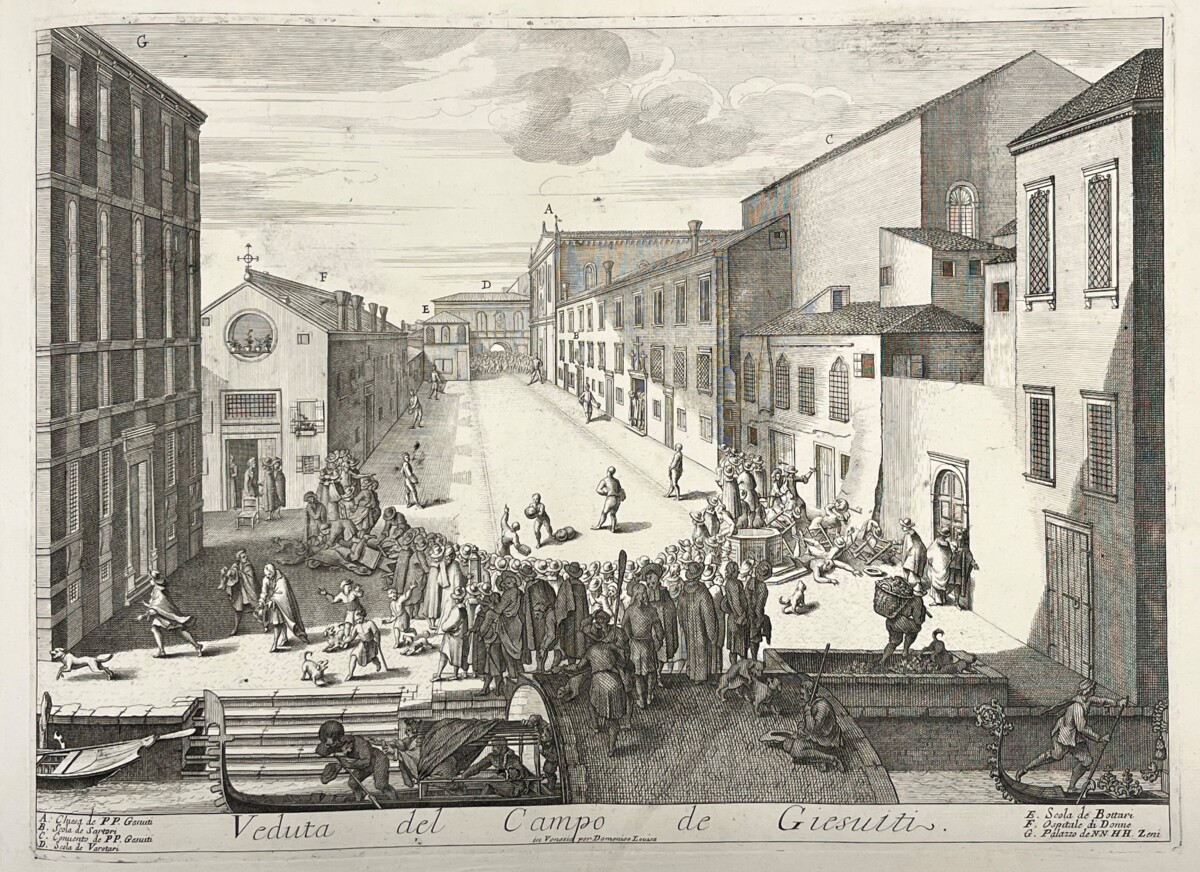

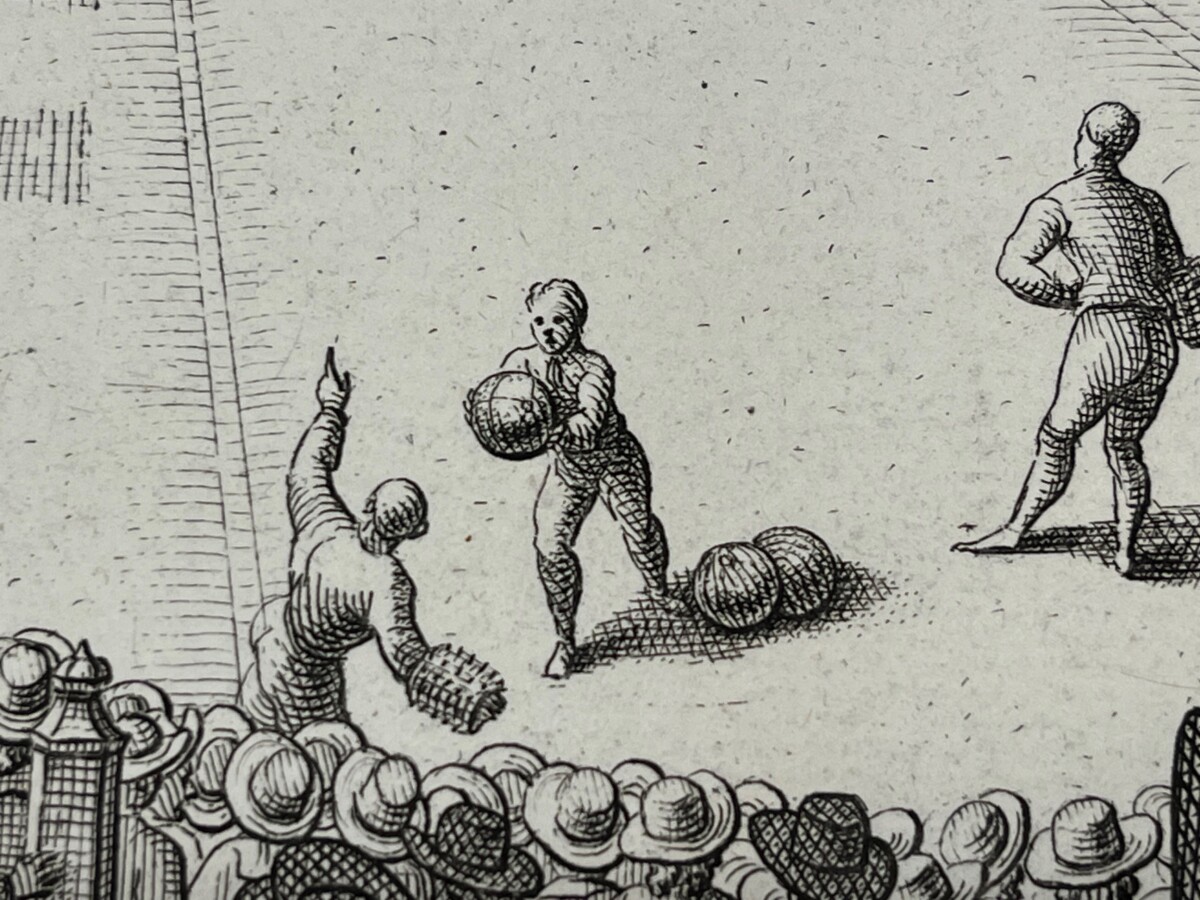

In addition to the famous buildings and religious and history paintings, the prints offer insights into aspects of everyday life in this bustling city in the early eighteenth century, ranging from detailed views of major public ceremonies, such as the Easter festivities in Campo San Zaccaria (above), to some less dignified but still significant sights, such as this scene (below) of a crowd in the Campo dei Gesuiti watching a ball game, one of the popular and sometimes violent urban pastimes that also attracted many spectators. The scene also throws light on a lesser known feature of life in the city: garbage disposal. In addition to the piles of broken furniture and other detritus visible near the crowd is an enclosure next to the canal denoting that this area is one of the “scoazzere,” designated enclosures where Venetians could leave everything that could not be tossed into the canals to be carried away by the tides that naturally removed most garbage twice daily. Once the scoazzere became full, boats would load up the trash and dump it outside the city.

Looking at a photo of the same square today, many of the locations shown in the book appear remarkably similar, even three centuries later.

Nicola Shilliam, Western Art History Bibliographer