On September 1,1923, Frank Lloyd Wright’s legendary Imperial Hotel [Teikoku Hoteru] opened to the public for the first time. Located near the emperor’s palace in Tokyo, it was built by the Japanese government to house foreign visitors and guests of the imperial family. “The Jewel of the Orient,” as the hotel was billed, offered luxurious accommodations that were touted as being more suited to Western guests than its Japanese competitors.

The hotel achieved “legendary” status, not because of the reputation of its renowned architect, but for the circumstances surrounding its premiere. Just before noon of opening day, the Great Kanto Earthquake—at the time the most devastating natural disaster to have ever hit Japan—leveled the cities of Tokyo and Yokohama. Over 140,000 people were killed by the 7.9 magnitude quake and the resulting fires. The Imperial Hotel was damaged, but survived destruction—information that the Wright publicity machine quickly disseminated East and West. It led to the hotel achieving a kind of mythical status around the world.

Marquand Library’s comprehensive collection of works related to the famous architect Frank Lloyd Wright includes a number of extremely rare books dating from the early to mid-20th century that are associated with the construction, promotion and ultimate destruction of his Japanese hotel. Two of these publications are particularly significant in their documentation of the history of the building because they pre-date the fabled opening. They offer the modern scholar an historical context and contemporary perception of the hotel that no longer existed once attention was refocused on the innovative construction techniques that allowed the hotel to survive the earthquake.

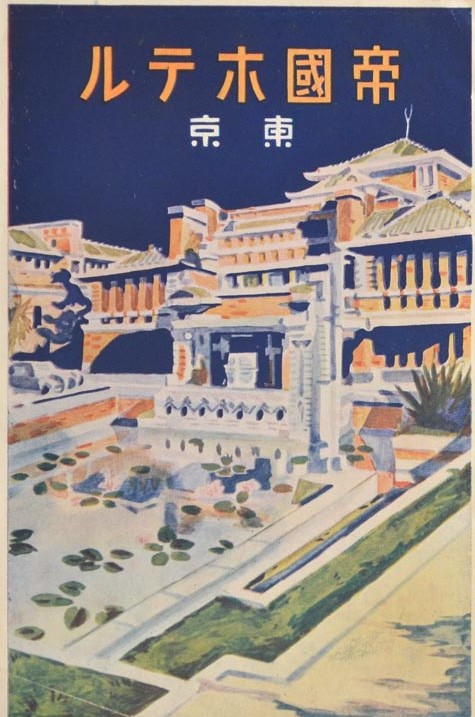

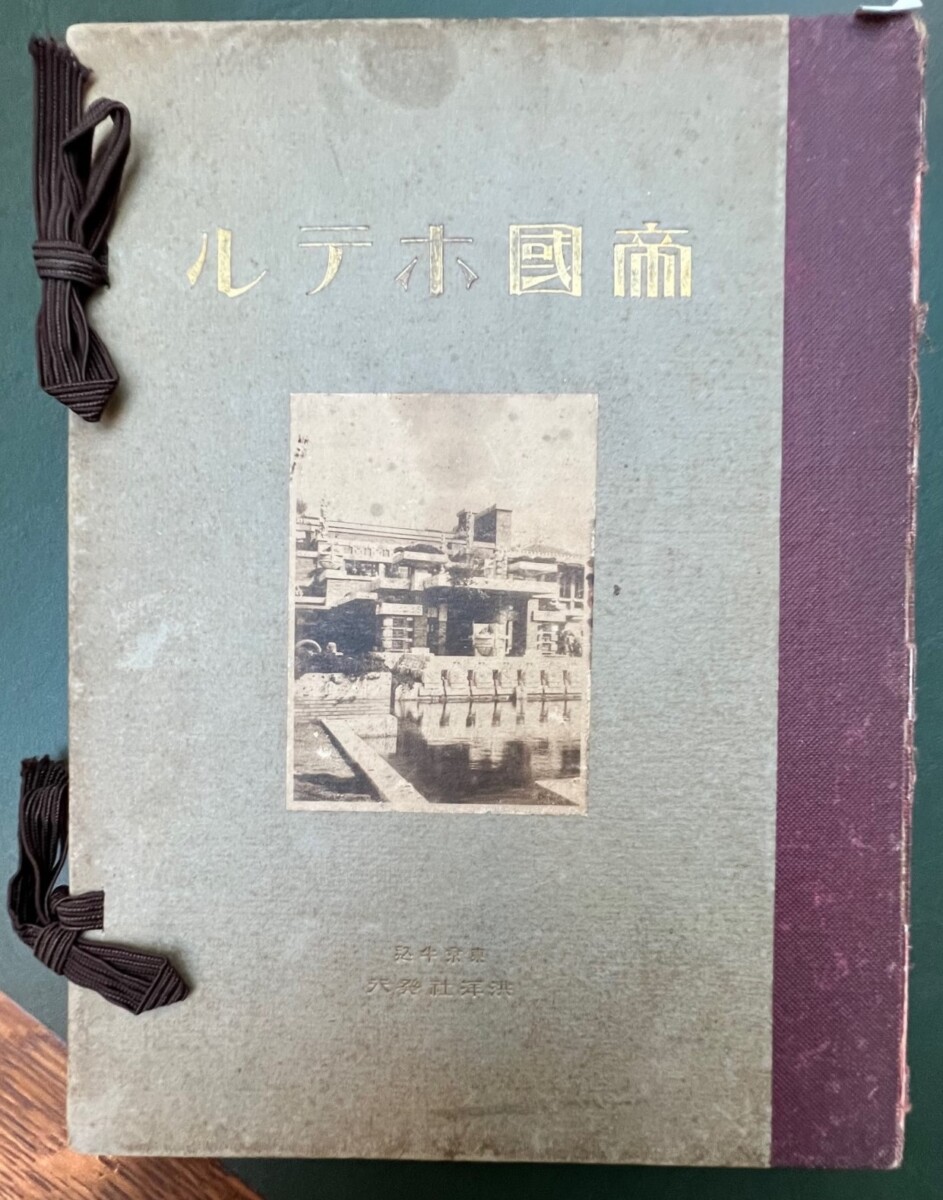

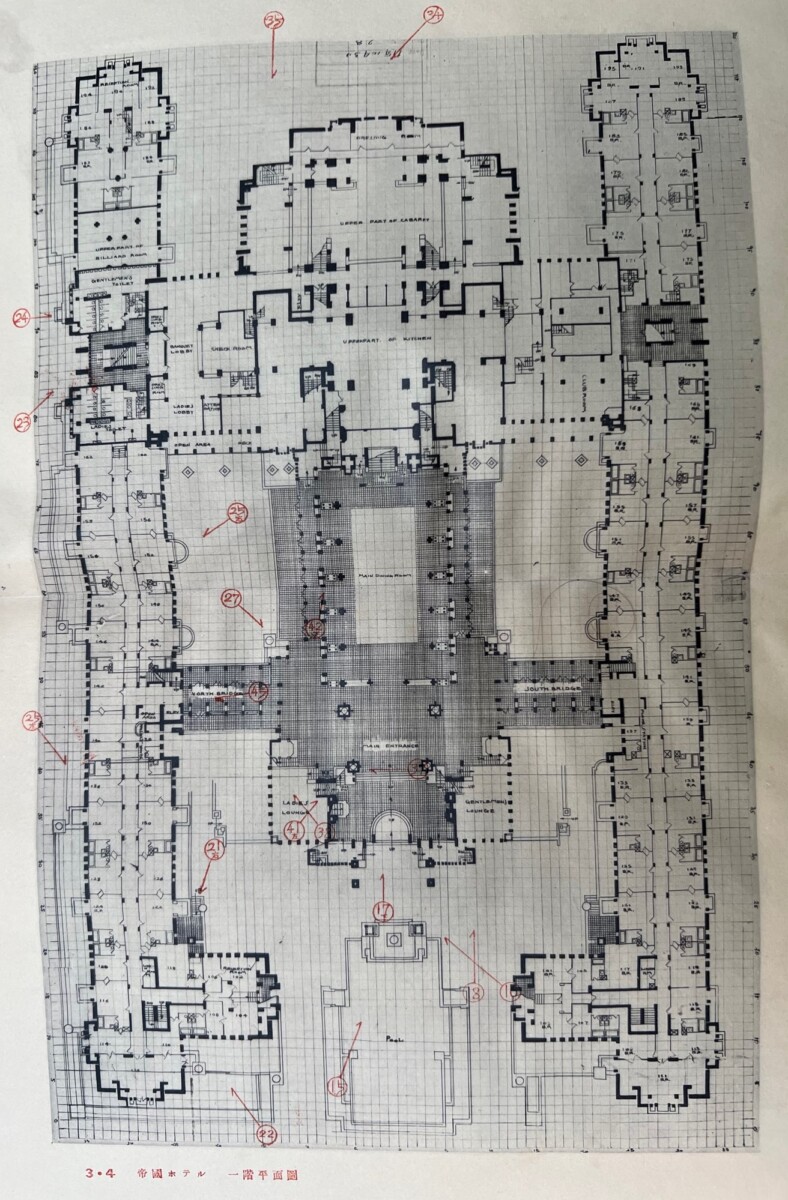

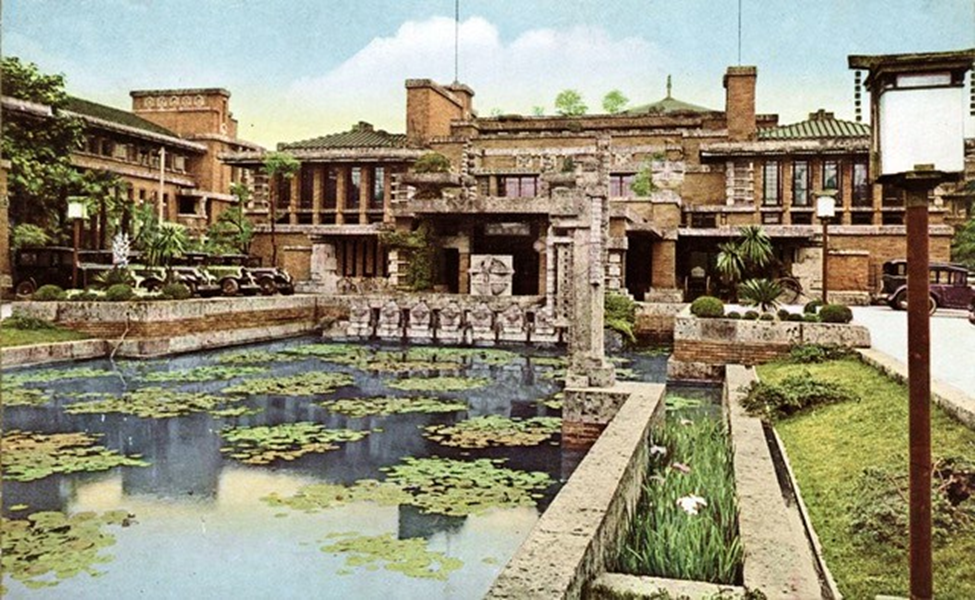

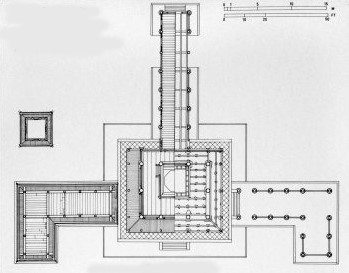

The first of these rare publications in the Marquand Collection is Teikoku Hoteru [The Imperial Hotel], published in August 1923, a month before the September opening. It is an expensively produced, comprehensive view of the hotel’s interior and exterior, featuring high quality photographs—some colorized—and detailed floor plans for each level of the building.

The floor plans include notations printed in red (but appearing to be hand-inscribed) that indicate the locations where each of the photos in the book was taken. This allowed/allows the viewer a true sense of the completed hotel. In his catalog essay on Wright’s own copy of this slender volume, which appeared in the 2017 Museum of Modern Art exhibition, Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive, Ken Tadashi Oshima speculates that it was through this book that Wright (who had left Japan a year before the building was completed) was able to experience the fully realized Imperial Hotel. (61)

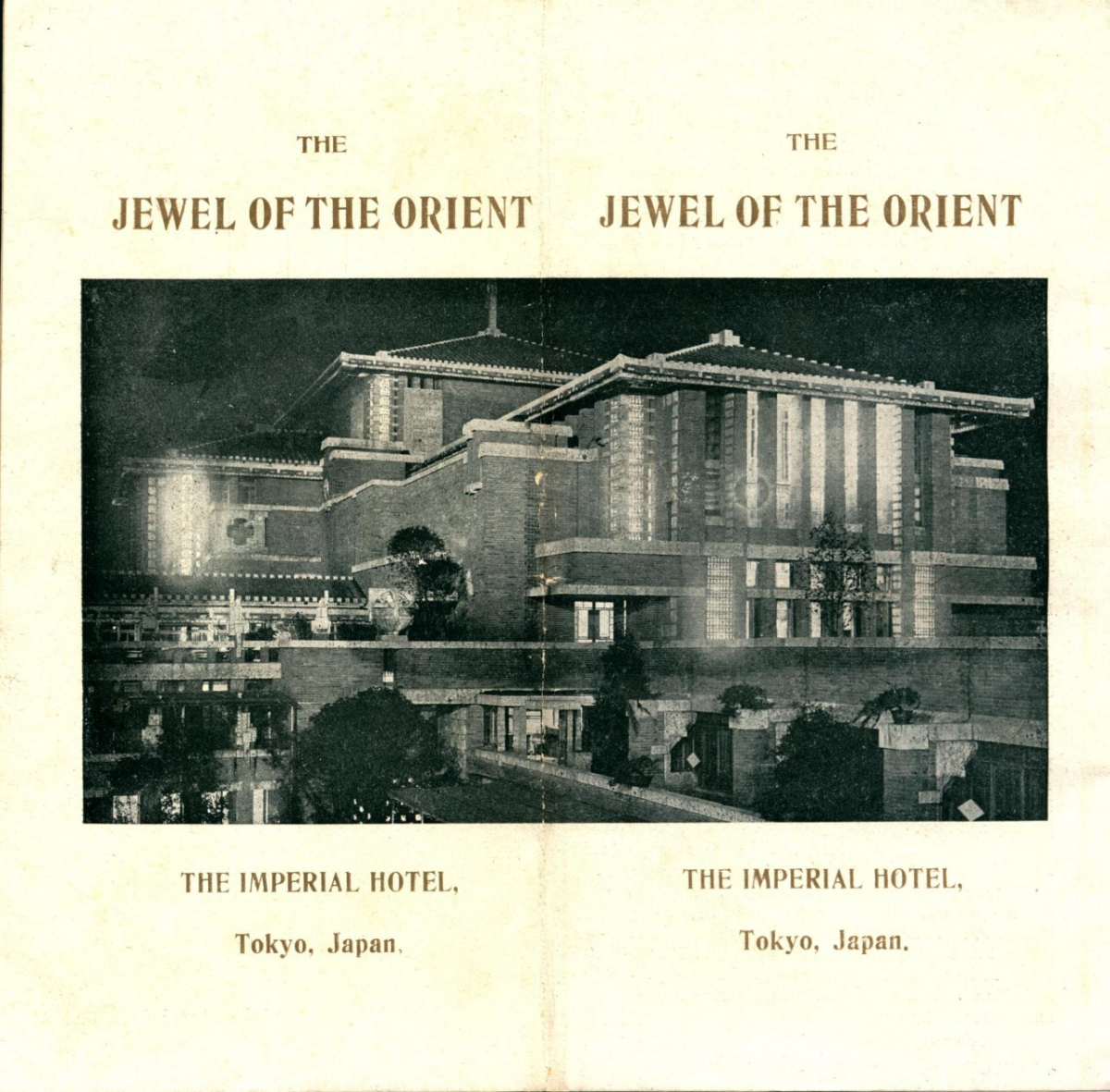

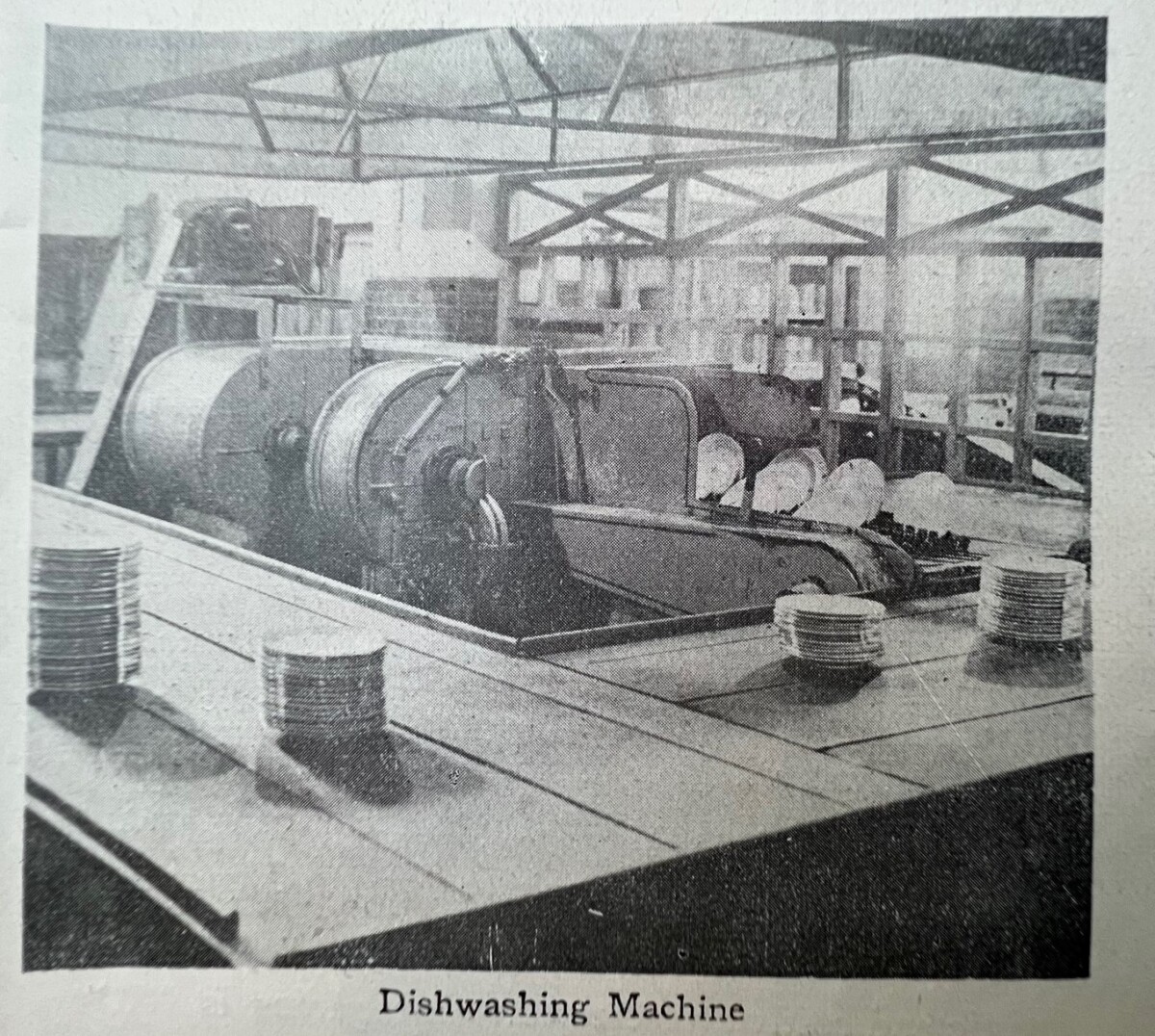

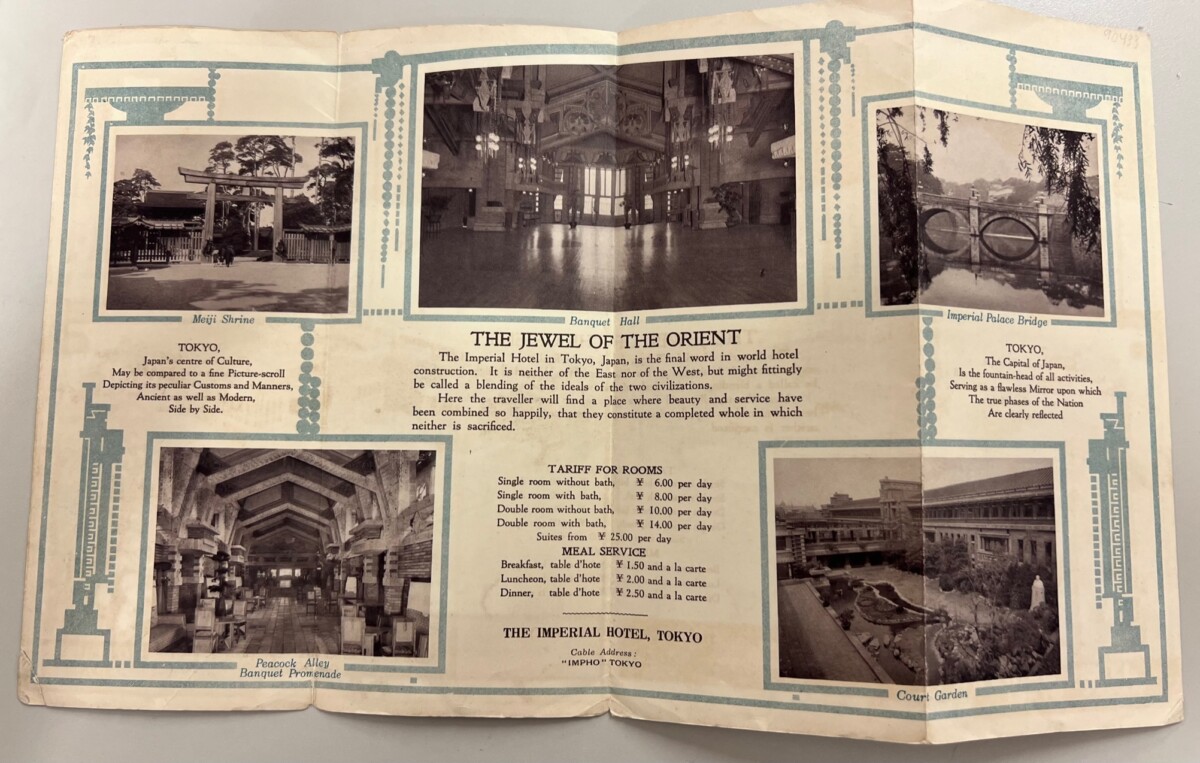

Also published in August 1923 was an English-language prospectus in booklet form, The Jewel of the Orient: The Imperial Hotel, Tokyo, which highlighted the grandeur and modern guest-related features of Japan’s new tourist destination. Today the ‘cutting edge’ amenities described seem quaint, but today, give us a real sense of period. In its 28 illustrated pages, for example, the brochure describes the luxuriously appointed public and private rooms, the arcade full of shops, the modern laundry, the ice-making plant, the roof garden, the aquarium for shellfish in the kitchen and, of course, the hotel’s ice cream-making machine! The Imperial Hotel also had its own orchestra, a theatre that sat 775 people, and an 8,000 square foot kitchen that was able to serve ‘the finest’ meals to 3,600 guests at a time. There was also a water distillation plant so that, as the brochure promises, “not a single drop of drinking water” would be served that had “not been distilled, thus ensuring its purity and immunity from disease bearing bacilli.”(23) In addition, they employed twelve men to man the four large automatic burnishing machines for the hotel silver and had a dishwashing machine so large that it could wash and dry 5,600 dishes an hour.

The “sales pitch” begins in the first opening of the brochure (see below), where the Imperial Hotel is advertised as setting architectural precedent in terms of form and function; it was a “blending of the ideas of the two civilizations”—a “symphony in brick and stone.” It continues with an almost comedic turn, advertising the hotel’s luxuriousness by bemoaning the unabandoned extravagance with which it was constructed:

Much has been written and much has been said about the new Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, Japan. Hard-headed businessmen who estimate all things in dollars and cents look upon it as a folly…The costly rugs scattered everywhere throughout the hotel for the thousands to tramp over daily are described as wanton extravagance. The apparent indifference of the management to the cost of hammered copper, glass, gorgeous upholsterings and the like, all bring down the wrath of the dividend seeker on the heads of the directors who approved of the structure, the architect who conceived and designed it and the builders who dared to construct it. To them the Imperial Hotel is a masterpiece of folly, a source of never ending expense and a case where pride took the bridle in its teeth and ran away with judgement and common sense.

Later in the booklet, Wright, himself, provides historical pedigree, boasting that the hotel is the “first important protest against the Gargantuan waste adopted by Japan from old German precedents.” It is, he continued, “a conservation of space, energy, and time…”

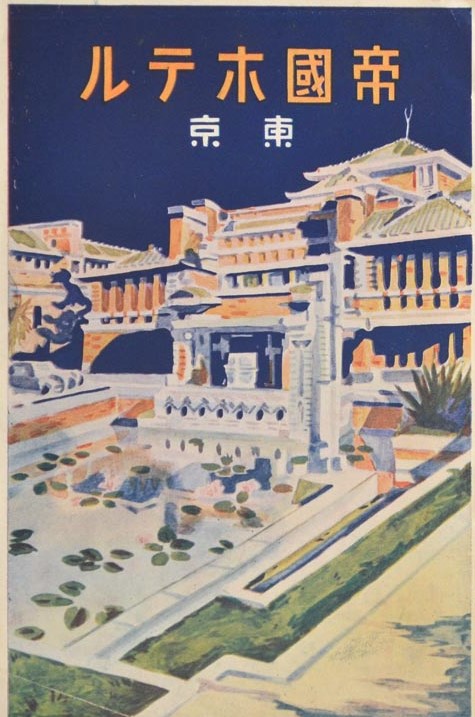

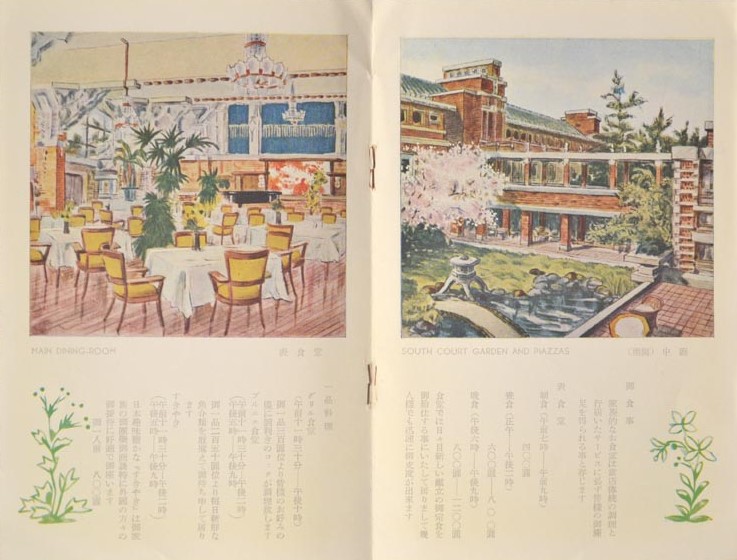

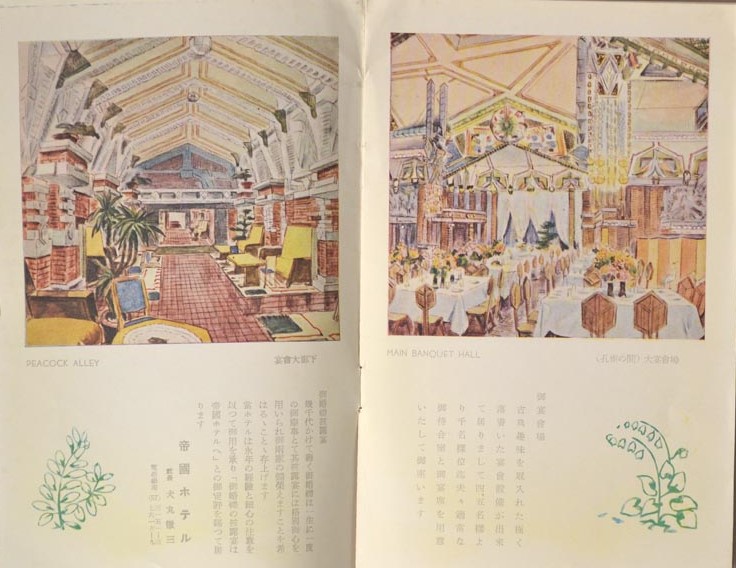

Recently, Marquand acquired two additional Imperial Hotel brochures that offer a view of the hotel’s “packaging” across the span of its lifetime. The first, dated ca. 1935, is written in Japanese with English captions. The beautiful printed illustrations appear to have had their origins in original paintings of the hotel.

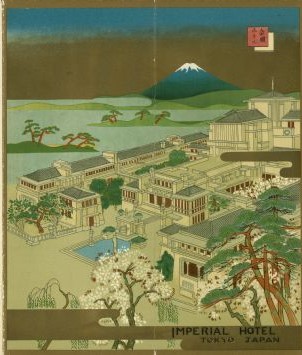

The second brochure, dating from ca. 1957 (34 years after the hotel’s opening and ten years before its demise) continues to advertise the grandeur of the setting, now incorporating a view of the famous Mt. Fuji on the horizon:

It is the acquisition of ephemeral publications like Jewel of the Orient and the later Imperial Hotel brochures that allow Marquand Library to provide the modern scholar with unique insights into the historical context of a significant architectural monument and the period in which it was built.

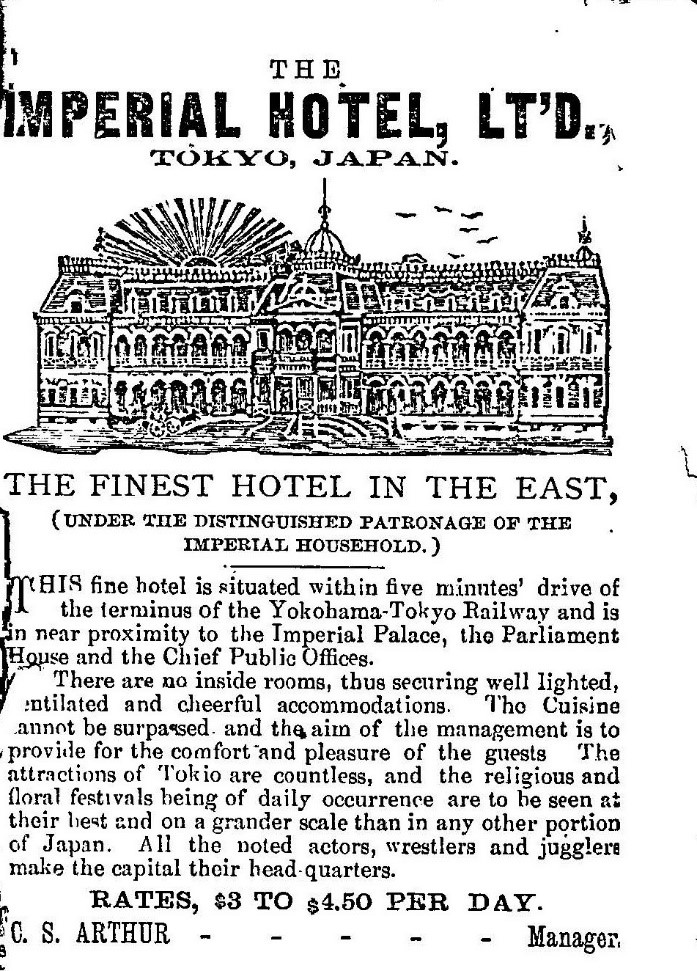

In studying the context of Wright’s Imperial Hotel, it is enlightening to compare its promotional material with that of its predecessor, the first Imperial Hotel, which opened to foreign businessmen and tourists on the same site thirty-three years earlier. An advertisement, featuring a drawing of the original—a neo-Baroque, French Second Empire-style structure—appears in an 1890 publication in the Marquand Collection entitled, Imperial Hotel: Guidebook and Map (published by the “Box of Curious” Printing Office, Tokyo). The 1890 structure was actually the first Western-style hotel built in Japan and, like its successor, offered luxurious lodging and the amenities that foreign visitors would expect. By 1911, however, the hotel could no longer accommodate the growing influx of Western guests, so plans were made to build a larger, more modern structure. Frank Lloyd Wright was tapped for the job, but it would be twelve years (more than four years behind schedule and over two million dollars over budget) before his new Imperial Hotel would be completed.

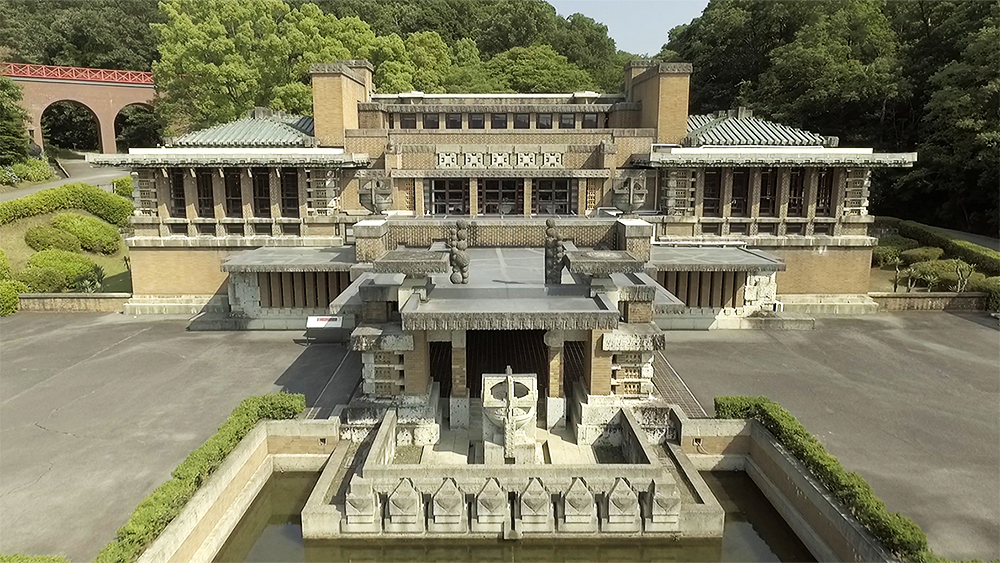

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Imperial Hotel was architecturally striking, faced with golden brick and local Ōya stone, an igneous rock that was easily carved and perfect for the building’s decorative elements. Although the building style, at the time, was deemed “Mayan Revival,” because of its “Mexican and Central American” decorative elements (seen here), Japanese art and architecture were clearly the inspiration for Wright’s design for the new Imperial Hotel.

Actually, Wright was already deeply immersed in the art of Japan when he received the commission. Though not well known, over his lifetime, Frank Lloyd Wright made more money as a Japanese woodblock print dealer than as an architect. He himself had a staggering collection of Japanese prints, paintings, ceramics and textiles. It would therefore not be surprising that these works would have been a source of inspiration for the architect. However, controversy about the influence that Japanese art and architecture had on Wright has always existed. The dispute lies in the fact that, despite clear evidence to the contrary, Wright often rejected the idea. He addressed the issue on several occasions throughout his career. Examples include:

Do not accuse me of trying to adapt Japanese forms…THAT IS A FALSE ACCUSATION AND AGAINST MY VERY RELIGION.

[1911 letter to Charles Ashbee]

…I found in Japan, not the inspiration everyone thinks I found…What happened to me was a great confirmation of the feeling I had and work that I had myself done before I got there.

[1956 recording of a lecture by Wright]

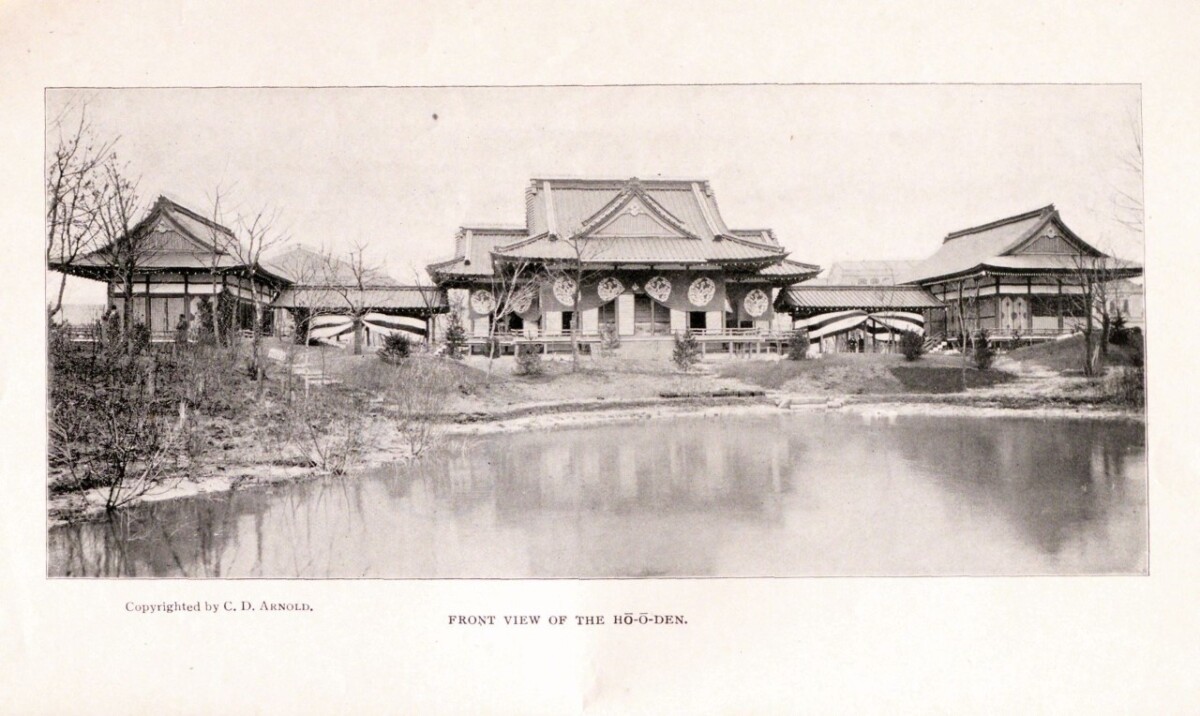

Despite Wright’s protestations, the Imperial Hotel was unquestionably inspired by Japanese architecture, or, to put it more bluntly: its structure and design are clearly derived from the Japanese Exhibition Hall at the center of the World’s Columbian Exposition that took place in Chicago (where Wright lived and worked) in 1893. It was a building with which Wright was very familiar:

The exhibition hall itself was a modern interpretation of what is still considered one of the hallmarks of Japanese architecture, the 11th-century Phoenix Hall of the Byōdōin Temple.

Built in 1052, the Phoenix Hall near Kyoto, Japan was a physical manifestation of the palace depicted in Buddhist paintings of paradise. There is a central square two-story edifice with identical wings of two-story-high colonnades, that stretch out from either side and then come forward at right angles. A corridor or “tail” is attached to the back of the hall, creating the overall aerial appearance of a phoenix in flight. There is a lotus pond in front of the building, which is integral to its design and purpose as a place to worship the Amitabha Buddha.

The Japanese pavilion at the 1893 exposition, designed by Japanese architect Masamichi Kuru, was modeled after the Phoenix Hall, one of his country’s most significant architectural treasures. He recreated the same central square structure with wings of the 11th century building, although the purely decorative colonnaded wings of the original now became functional interior space to house the Japanese treasures on display at the exposition. In homage, Masamichi also called his building “Phoenix Hall” or “Ho-o-den.”

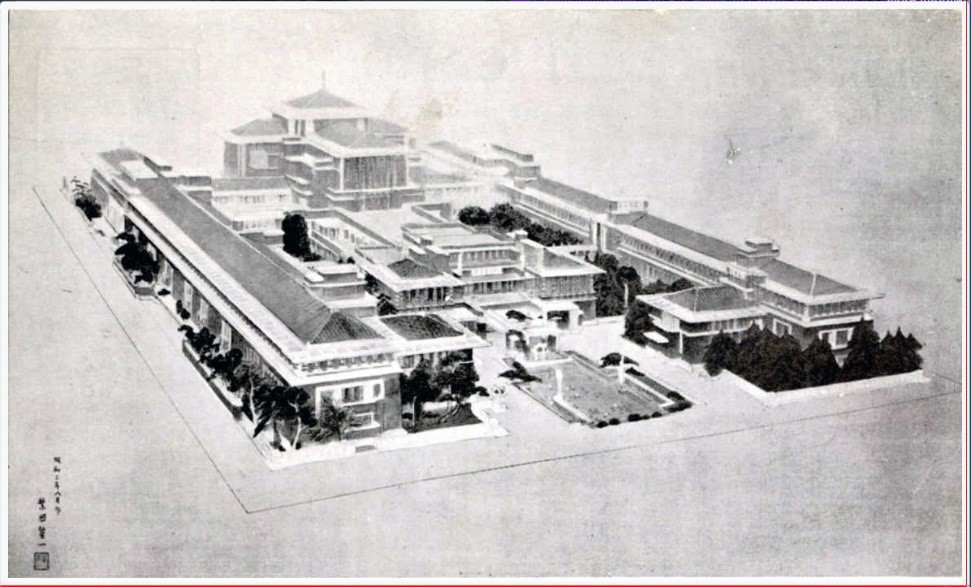

As can be seen in the photo of Wright’s final drawing of the building, the Imperial Hotel is based on this same model. It is no secret that Wright had intimate knowledge of the Chicago Phoenix Hall. He had been hired to work on the Exposition’s Transportation Building and is known to have visited the construction site daily to view the Japanese craftsmen constructing the hall from the ground up. In addition, the pre-Exposition hype included a feature in the Chicago journal, Inland Architect (December 1892), which included complete and detailed architectural drawings of the Masamichi’s Japanese pavilion. The article created such a buzz in Chicago that over 10,000 people a day were visiting the construction site to see the creation of this wonderful gift from the Meiji Emperor. It is therefore unlikely that Wright did not know about or have access to these detailed plans. The access and drawings provided Frank Lloyd Wright with both a model for the Imperial Hotel and, more importantly, with his overall approach to architectural design. His hotel, however, needed to be much larger than either a small Buddhist hall or exposition pavilion. Wright therefore enlarged the cruciform plan of the earlier structures by adding a second central building attached by a “tail” corridor (like the one seen in the original Phoenix Hall). The wing extensions were also expanded and are attached to both central buildings. To reproduce the landscaping of the original Phoenix Hall, which Wright visited during the years he lived in Japan, the architect located a lotus pond at the entrance to the hotel.

In 1967, the Imperial Hotel was torn down. Damage done by the earthquake forty-five years earlier had caused the building to sink and become unstable over time. A collection of photographs taken just before and during the building’s destruction is to be found in another book in Marquand’s collection: The Imperial Hotel 1921-1967, by Watanabe Yoshi (1968). It is a visual record of the architectural details of the carcass of Frank Lloyd Wright’s once imposing structure. Because of the historic significance of Wright’s Imperial Hotel, however, the entrance, lobby and lotus pond were rescued and moved to the Meiji-Mura Museum in Aichi prefecture—a park opened in 1965 to preserve important Japanese buildings from the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

To celebrate the 100th anniversary of its opening, the new Imperial Hotel in Tokyo has opened a Frank Lloyd Wright suite in its high-rise structure, which has been made to resemble a 1923 guest room—complete with original furniture, carpets and lighting.[1] For a mere $10,800 a night, readers interested Frank Lloyd Wright’s Imperial Hotel can now experience “the legend.” https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/frank-lloyd-wright-suite?utm_source=nl&utm_brand=ad&utm_mailing=ARD_Daily_AM_012523&utm_campaign=aud-dev&utm_medium=email&bxid=5bea00023f92a404693b1e89&cndid=38161449&hasha=7d7c5624797e336c28ea4aceebb049c4&hashb=9fb54e44bfcf3ffa995b05d9a95ab73de3f489c9&hashc=6046caf813ffa7e5d5caa5db511708677c4a042d32f4bce405efb4d1ba78340f&esrc=OIDC_SELECT_ACCOUNT_&utm_term=ARD_Daily

[1] Since publishing, lori Hamada from Hotel Operations Management, Public Relations at the Imperial Hotel informed me that “the suite was actually opened in 2005 and was mostly only available to heads of state. Since we wanted guests to experience the Wright’s legacy we decided to open the doors to the general public this year only since it is the 100th anniversary.”- Nicole Fabricand-Person, Japanese Art Specialist