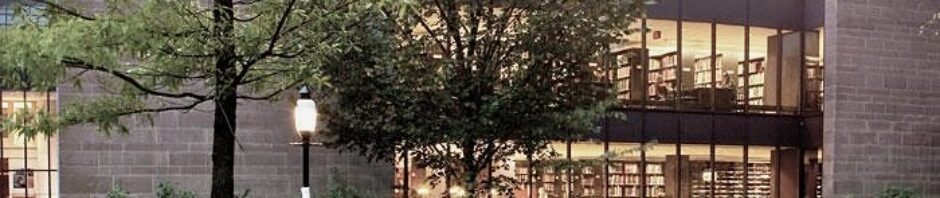

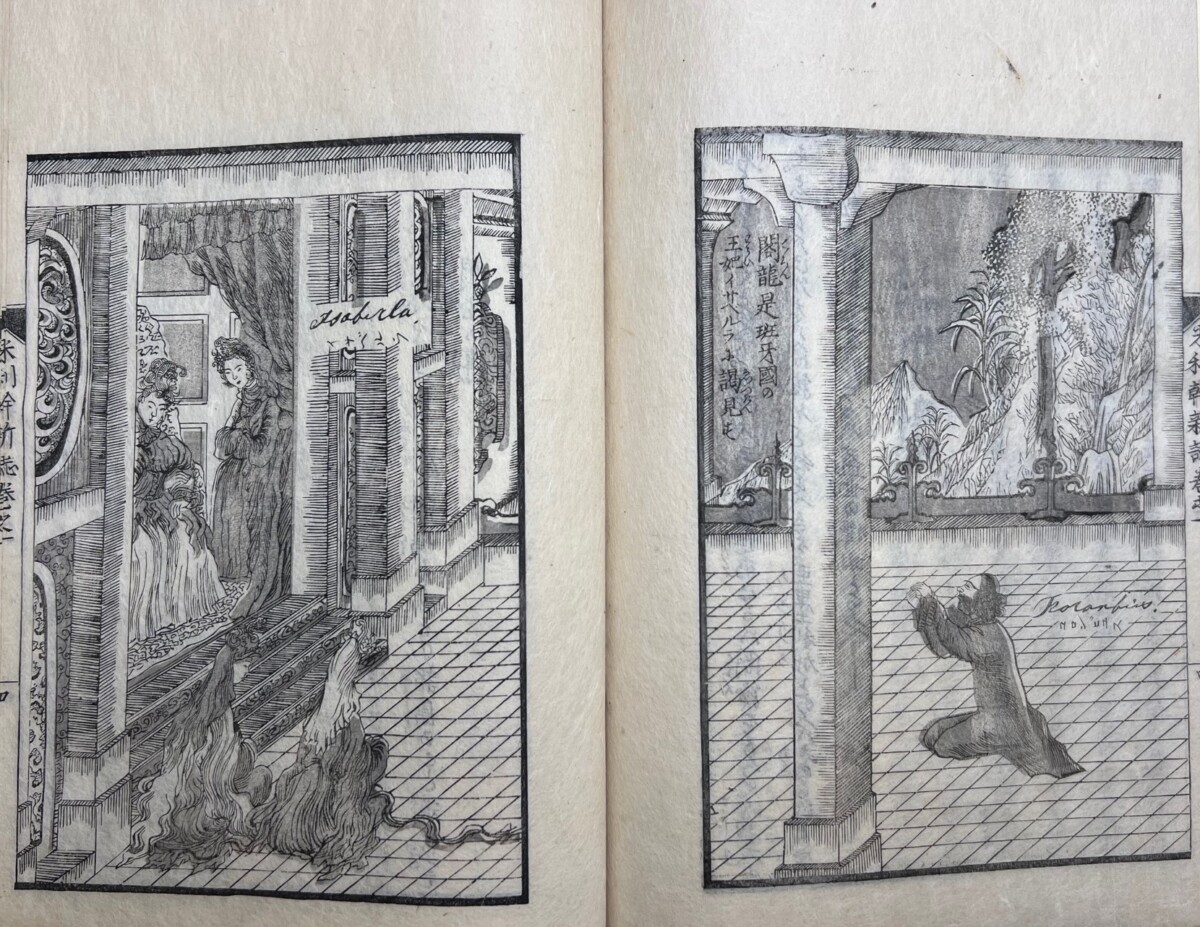

We all remember that classic tale of George Washington as a young boy—no, not the one about him chopping down the cherry tree—the one where he met with the Italian explorer, Amerigo Vespucci (1451-1512) on a balcony overlooking a random city? This literally legendary meeting is one of the first illustrations in the 5-volume Japanese history of America, New Account of America [Merika shinshi]1, written between 1853 and 1855.2

While scenes like this have been called ‘garbled’ or ‘misunderstood’ history,3 I would suggest instead that this might be an illustration of the young man who would become the first president of America symbolically paying tribute to the long dead explorer whose first name, here designated as “Amerikus,” would be used by cartographers to label the continents of the New World and ultimately give George’s nascent country its name.

The date of this 5-volume set, which claims to give a full account of America, is significant. In 1853, after Japan’s two hundred years of self-imposed isolation, Americans, under the command of Commodore Matthew Perry, arrived in Japan and demanded that the Japanese “open their ports” and sign trade agreements with the United States. A year later, in 1854, when Perry returned with an even larger fleet, the Japanese relented and began a trading relationship with the United States. New Account of America was written and illustrated during this transitional period, when there was intense curiosity about Americans and the Americas among the Japanese. It is believed to be the first book on the subject. The information here, however, is probably not from American sources, but from books that filtered into Japan through the Dutch, Japan’s only Western trading partner during its long period of isolation.

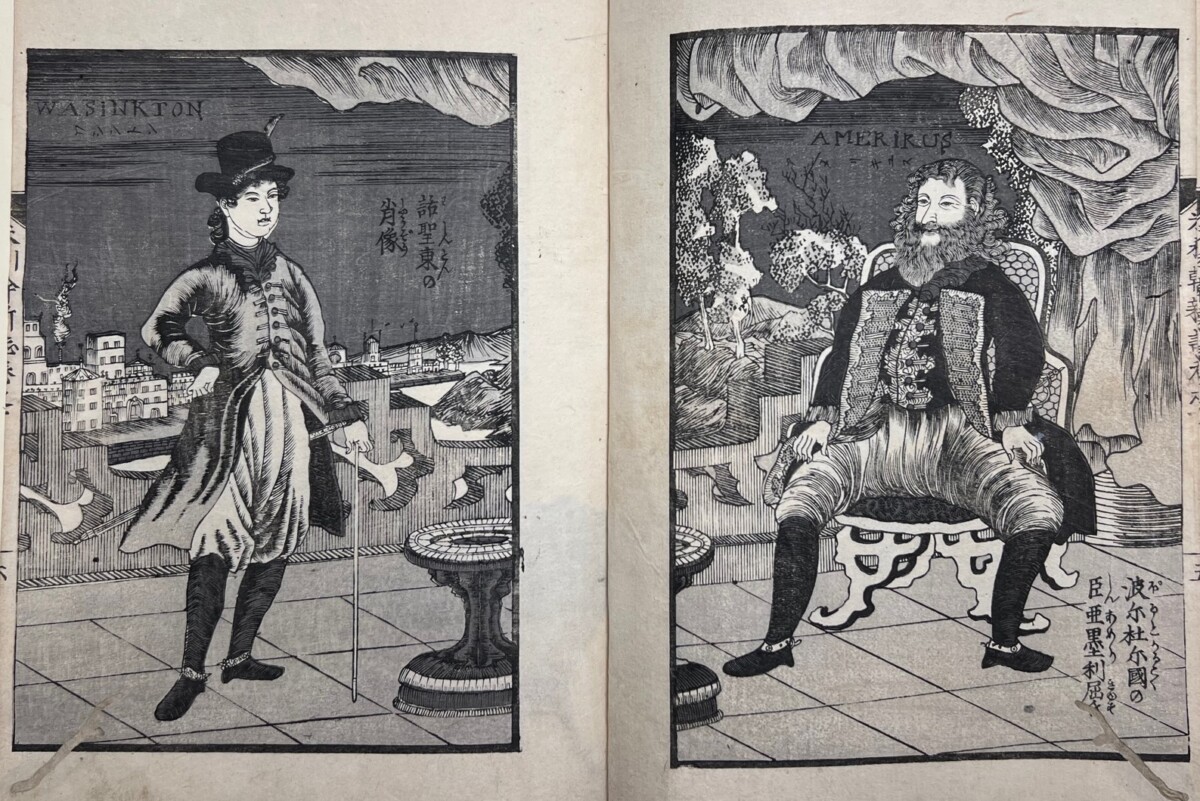

It appears that there was an attempt on the part of the publisher, Kasugarō, to add a touch of Western authenticity to the publication by giving it the appearance of Dutch books known to the Japanese in the 19th century. The cover, though paper, is the reddish brown of fine leather. The thickness of the paper adds to the sensory tactile illusion. Each cover is identically decorated with round medallions that bear designs, images and busts of Europeans, and what some have called the “American eagle” on them. They are all printed in blue ink and may represent the coins of North and South America.

New Account of America was written by the scholar, Tsurumine Shigenobu (1786-1859) and is believed to have been illustrated by Utagawa Sadahide (1807-1873),4 who became famous for his woodblock print depictions of foreigners at the port of Yokohama a few years after this book was published. Sadahide, a pupil of Kunisada (whose work was highlighted in a previous blog),was so admired that he was one of the ten artists chosen by the Tokugawa government to represent Japan at the 1867 Exposition Universelle de Paris, which introduced the Japanese print to Europe for the first time. He was awarded the Légion d’Honneur for his woodblock prints.

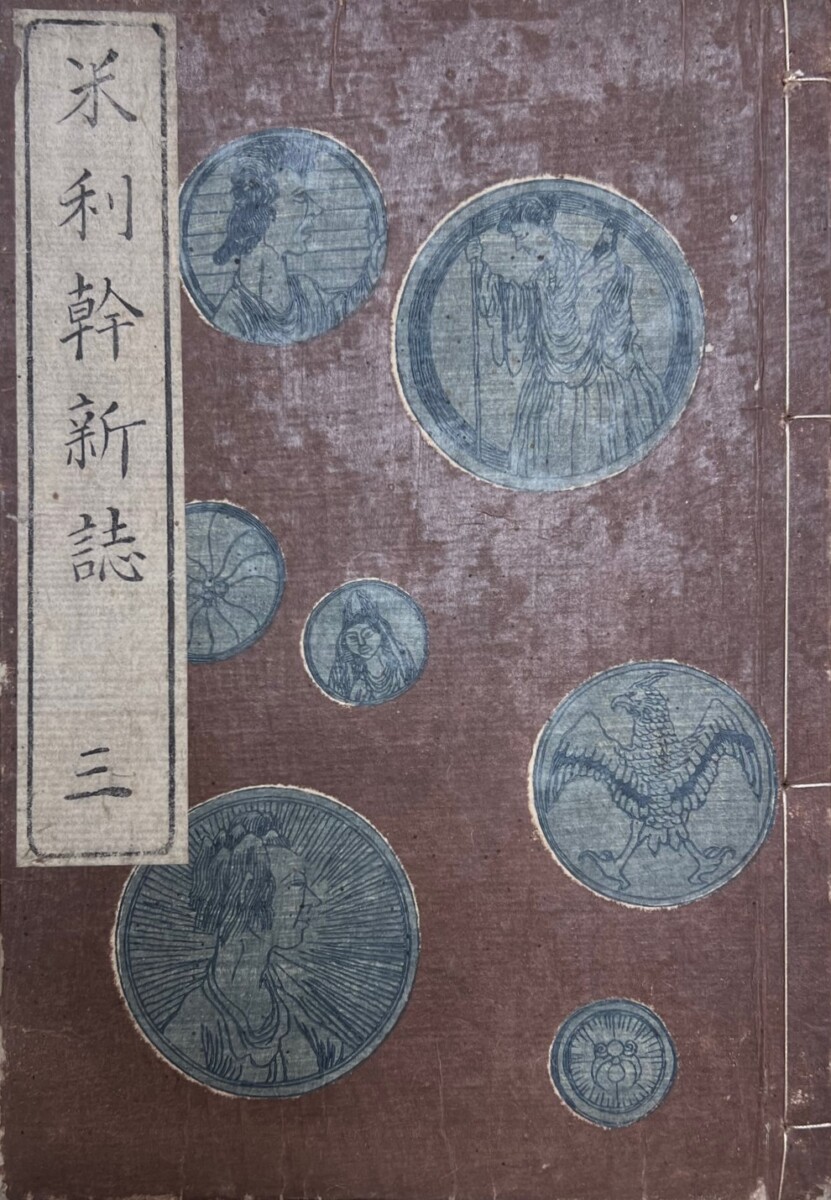

Much of New Account of America is devoted to George Washington and to Christopher Columbus, with two double-page illustrations of his begging Queen Isabella for the funding for his trip to India, which then led to the supposed “discovery” of the Americas. There is also quite a bit of statistical information on the individual states at that time, a description of the capital, and a discussion of the workings of the American government. Descriptions of battleships get more ink than Canada, which is only briefly mentioned, and the information on South America is, as will be seen below, spotty.

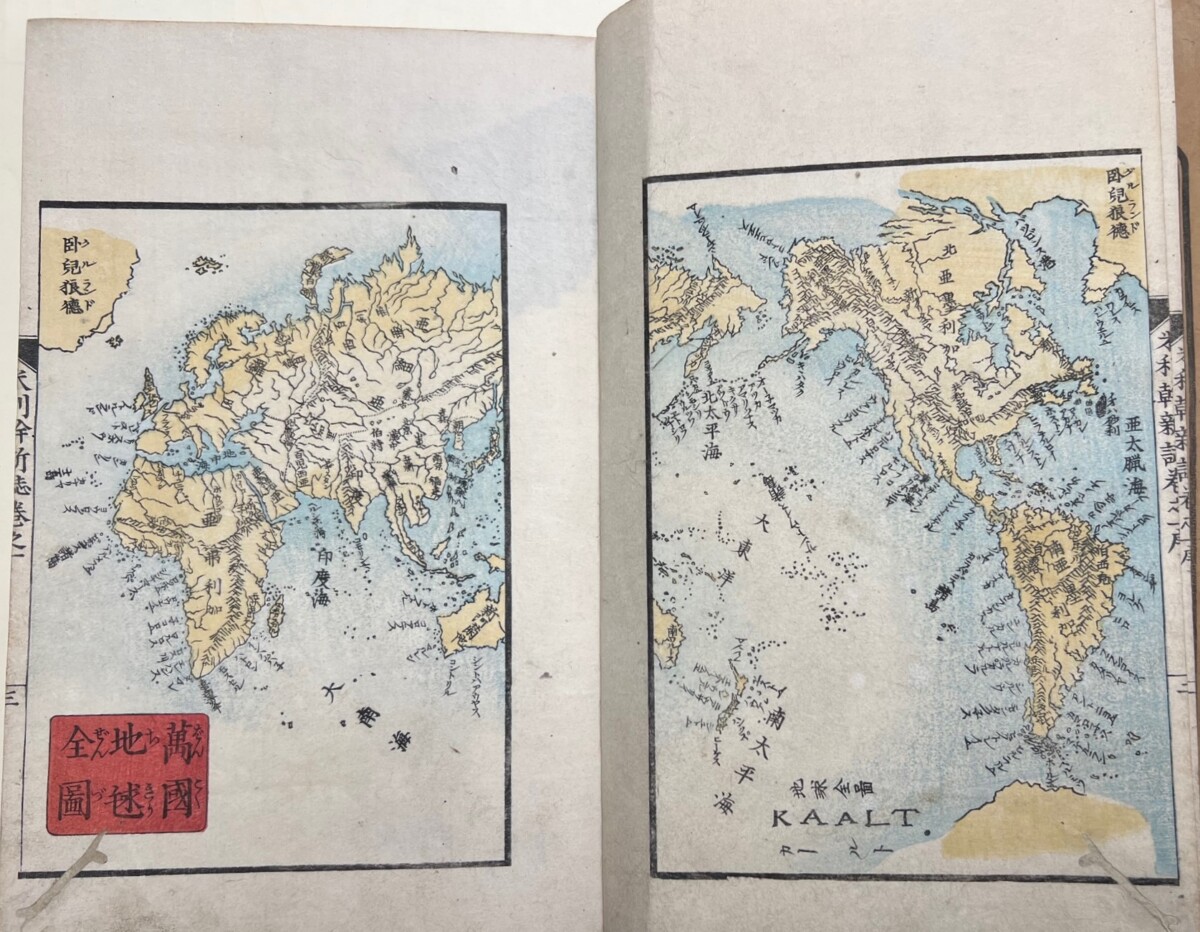

Volume 1 is largely devoted to the discovery of America and, in addition to the illustrations of Columbus, above, it includes maps of the world as it was known in the mid-19th century.

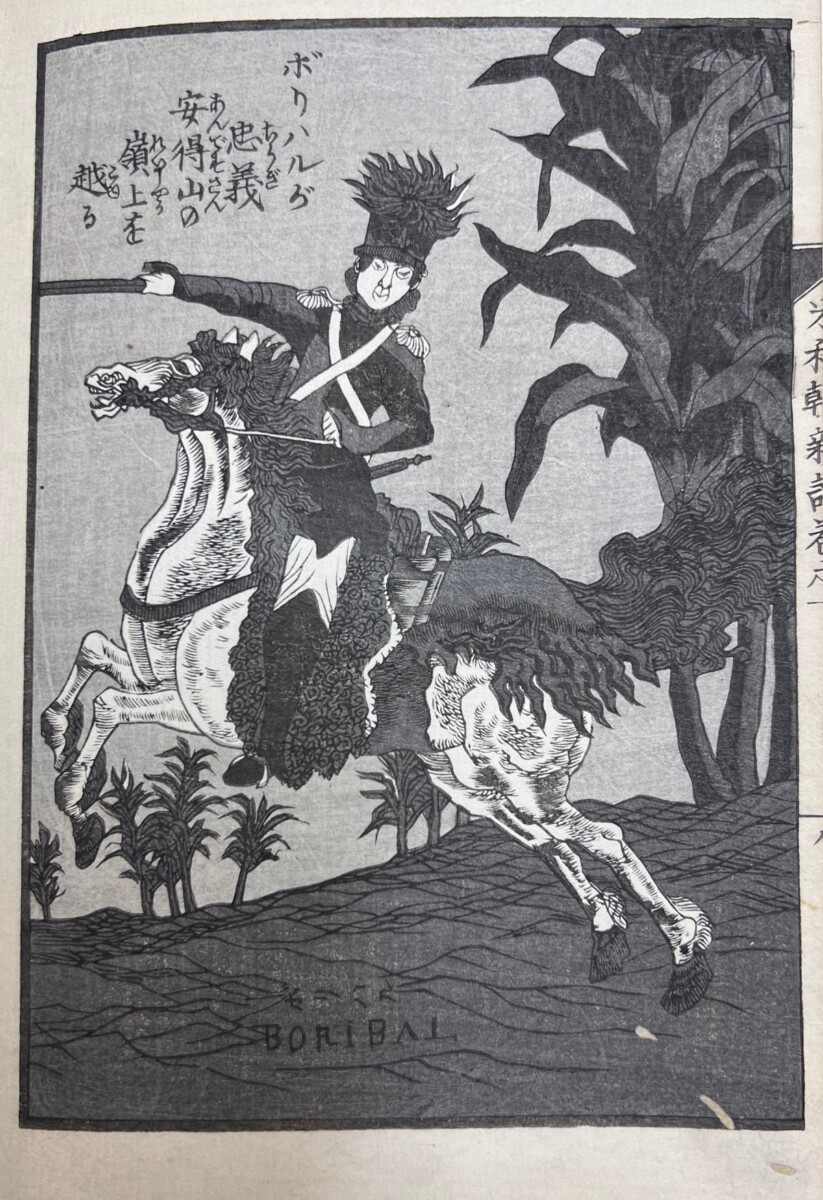

This volume also includes the Washington/Vespucci image and what may have been perceived as its counterpart: a dynamic portrait of Simón Bolivar, “The Liberator,” who led much of South America to independence from the Spanish empire.

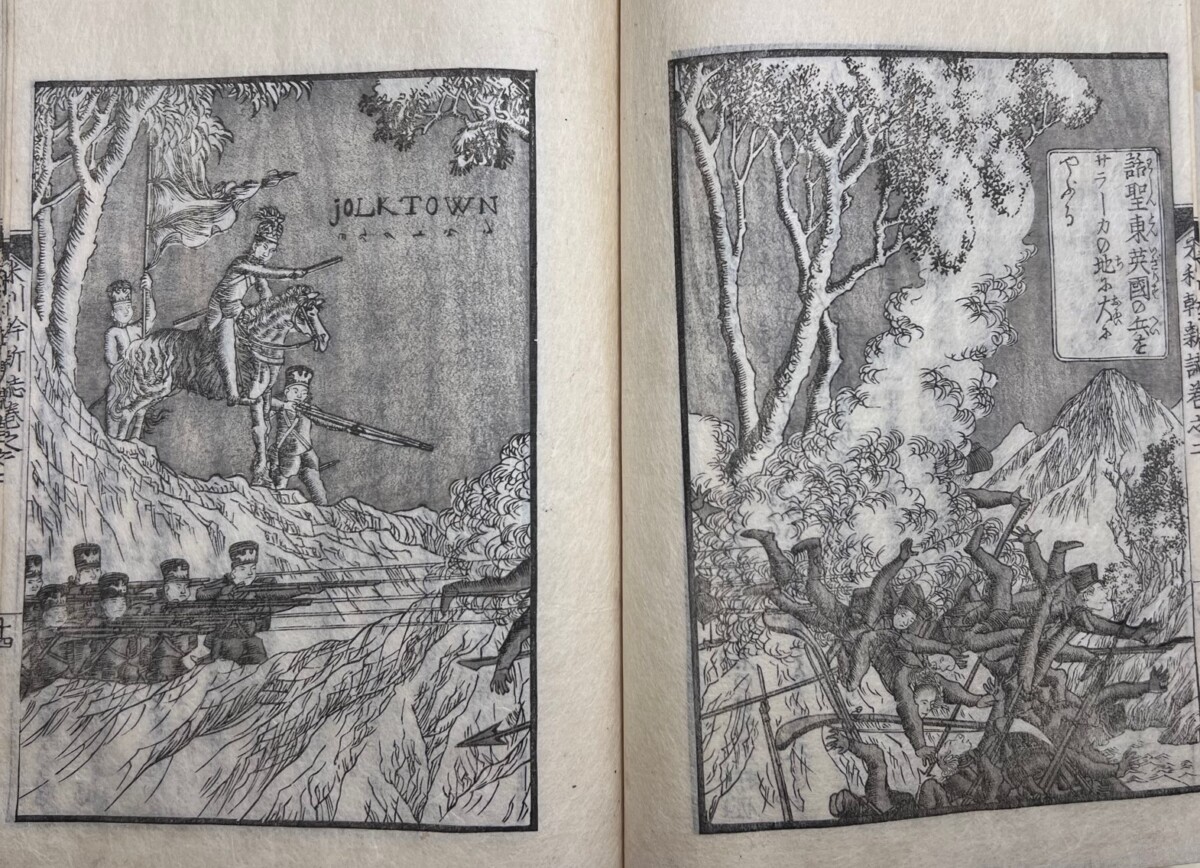

Volume 2 focuses on the Revolutionary War and its illustrations are heroic battle scenes filled with sprawling bodies like that of the Battle of Yorktown (Jolktown) below.

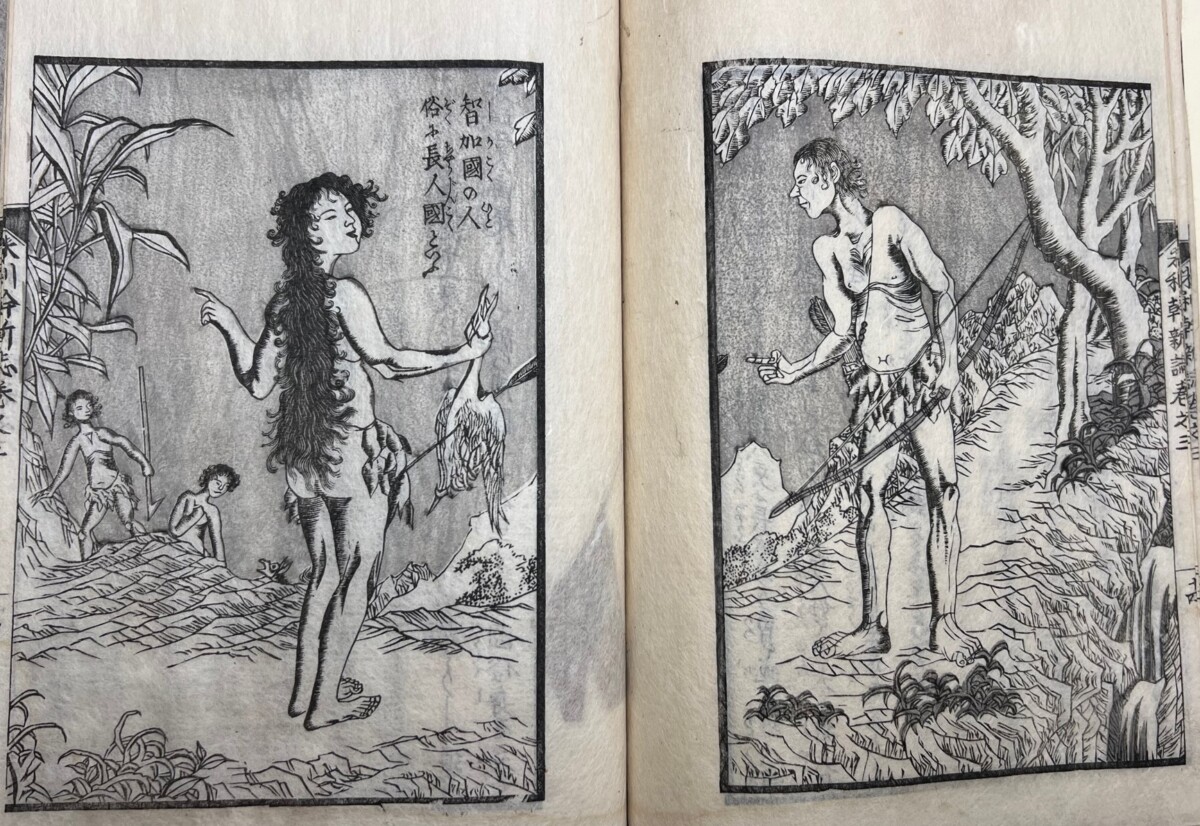

Volume 3 returns to the subject of Bolivar’s fight for independence and to South America in general, with images like the one of Chile and its inhabitants below.

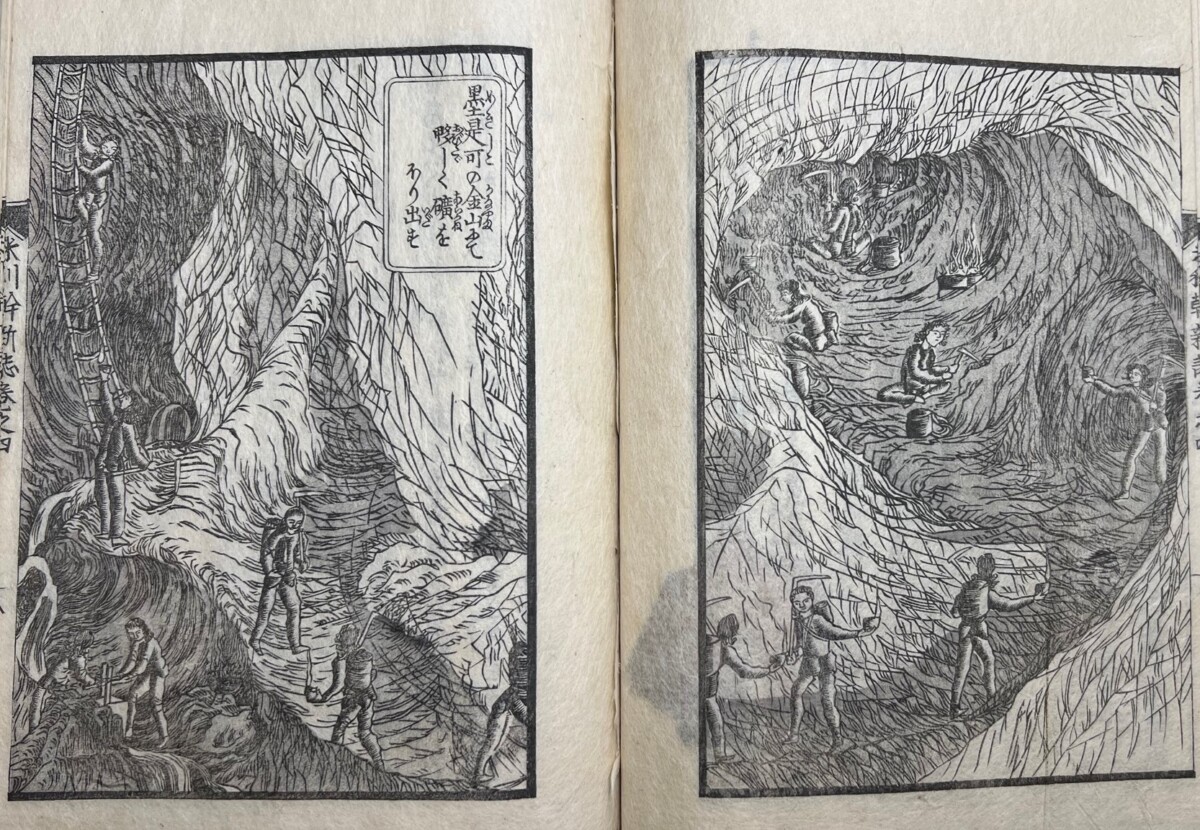

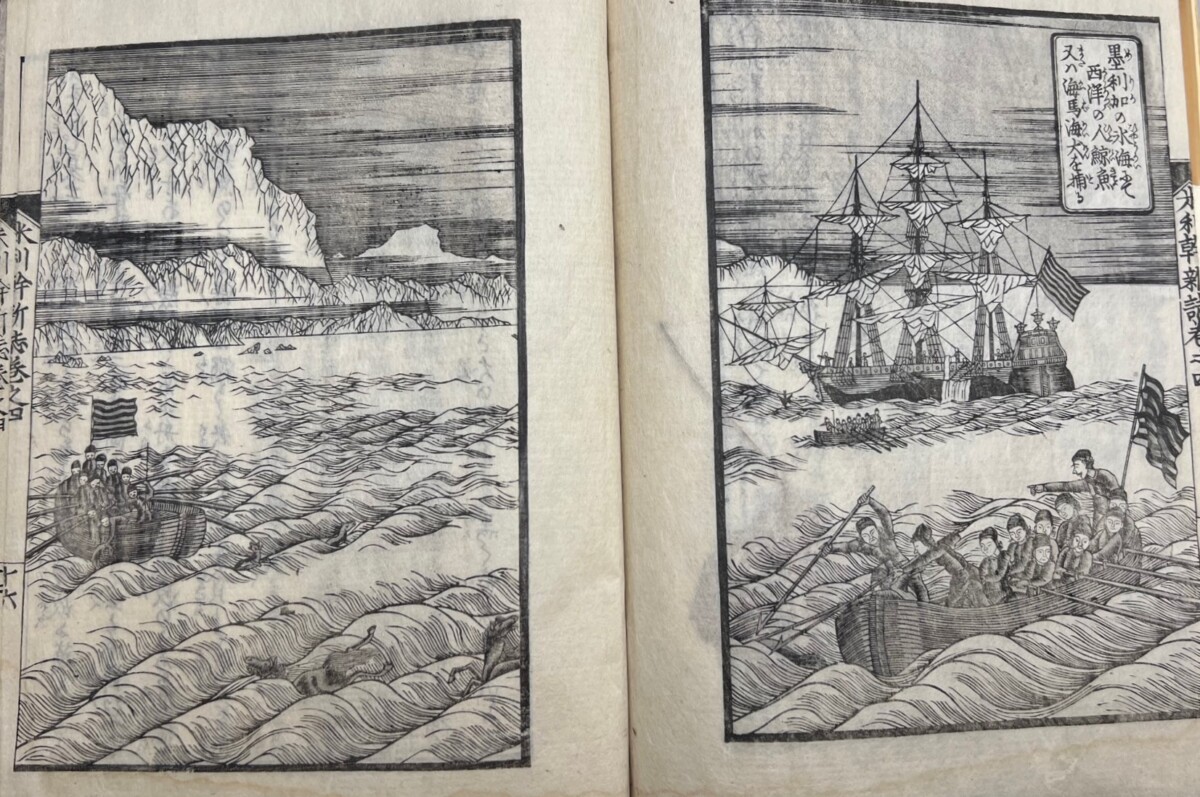

Volume 4 moves to the industry of the Americas and includes illustrations of a Mexican silver mine and whaling—where the whalers appear to encounter “seahorses,” which have been depicted as tiny horses among the waves.

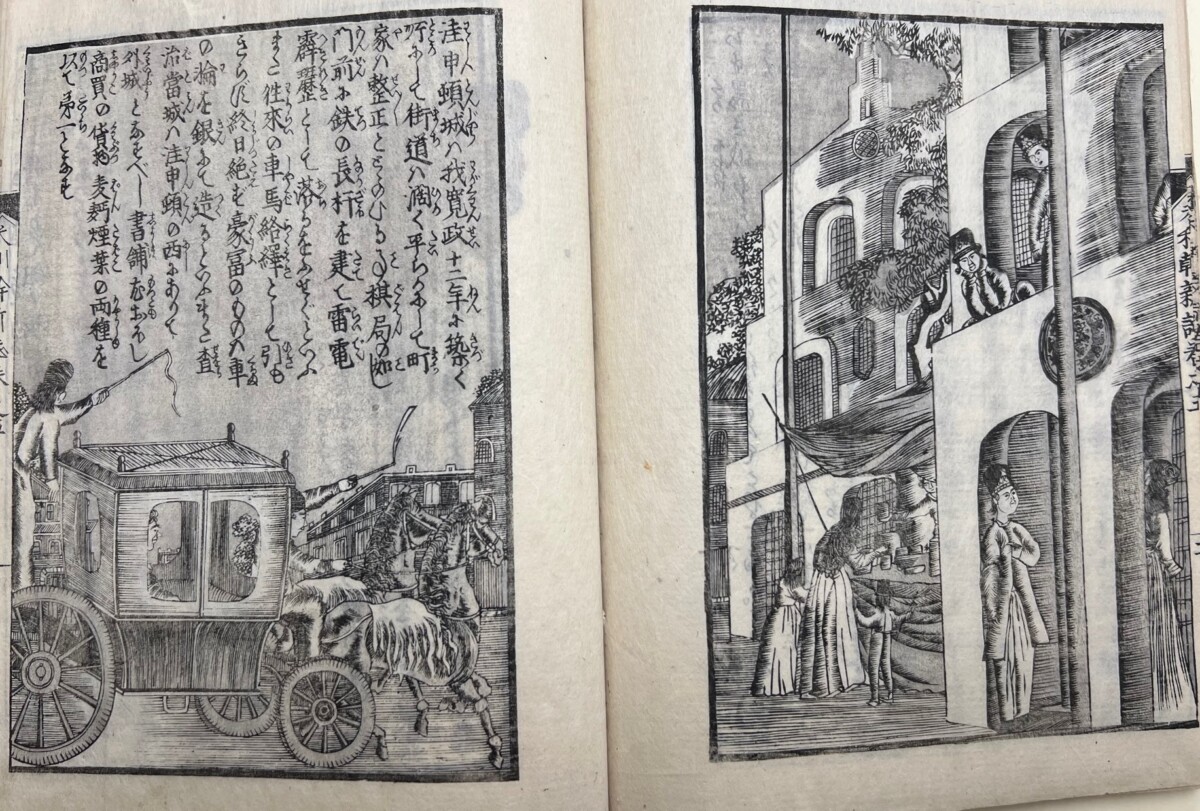

There are more battles depicted in Volume 5, followed by a picture of the city of Washington, where it notes that the streets are filled with carriages, there are many bookstores in Georgetown, and bread and tobacco are sold in large quantities.5

While the images like the ones in New Account of America can appear quite charming to us today, there is dark side to Japanese adoption of the conventions for illustrating peoples of other nations from models created by White colonizers. The images of the Chilean “savages” in this book give us some sense of how racist views about a culture or a people can be promoted and then fixed in the minds of others. For more information on Japan’s adaptation of racist images from the West see my article, “From the Wild West to the Far East: The Imagining of America in a Japanese Woodblock Print,” The Record, Princeton University Art Museum. Volume 68, 2009: 16-37 and my chapter, “Images of American Racial Stereotypes in Nineteenth-Century Japan,” in Cynthia Mills, et. al., East-West Interchanges in American Art: A Long and Tumultuous Relationship. (Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, 2012.), p. 80-94.

Marquand Library is fortunate to have other important works by Utagawa Sadahide, including a “draft book” with drawings of an as yet unidentified historical story about heroes of Japan, with characters resembling the great generals Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu (ca. 1848-1868). Also in the collection, is one of Sadahide’s most famous books, Things Seen and Heard at the Yokohama Open Port [Yokohama kaikō kenbunshi] (1862-1865) and a large fold-out map of Yokohama [Gokaikō Yokohama no zenzu] (1859).

- Nicole Fabricand-Person, Japanese Art Specialist

- 米利幹新誌. This title has alternatively been Romanized as Merikan shinshi and Meriken shinshi.

- The date of the preface in the first volume is 1853. The postscript at the end of Volume 5 is dated 1855. Although, some scholars have suggested that the book must have been completed by 1853 (and the postscript added later), because the maps do not show the Gadsden Purchase of that year, it is likely the news of the change in the shape of the borderline with Mexico may not have reached Japan within a few months’ time. The inclusion of borderline of California on the North American map, however, does mean that New Account of America’s earliest date of publication could have been 1948 when the state was acquired.

- Jack Hillier, The Art of the Japanese Book. (New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1987), p. 926-7.

- Also known as Gountei Sadahide and Gyokuransai Sadahide.

- Jack Hillier, The Art of the Japanese Book. (New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1987), p. 928-9.