The Magazine Jazz and French Colonialism in 1931

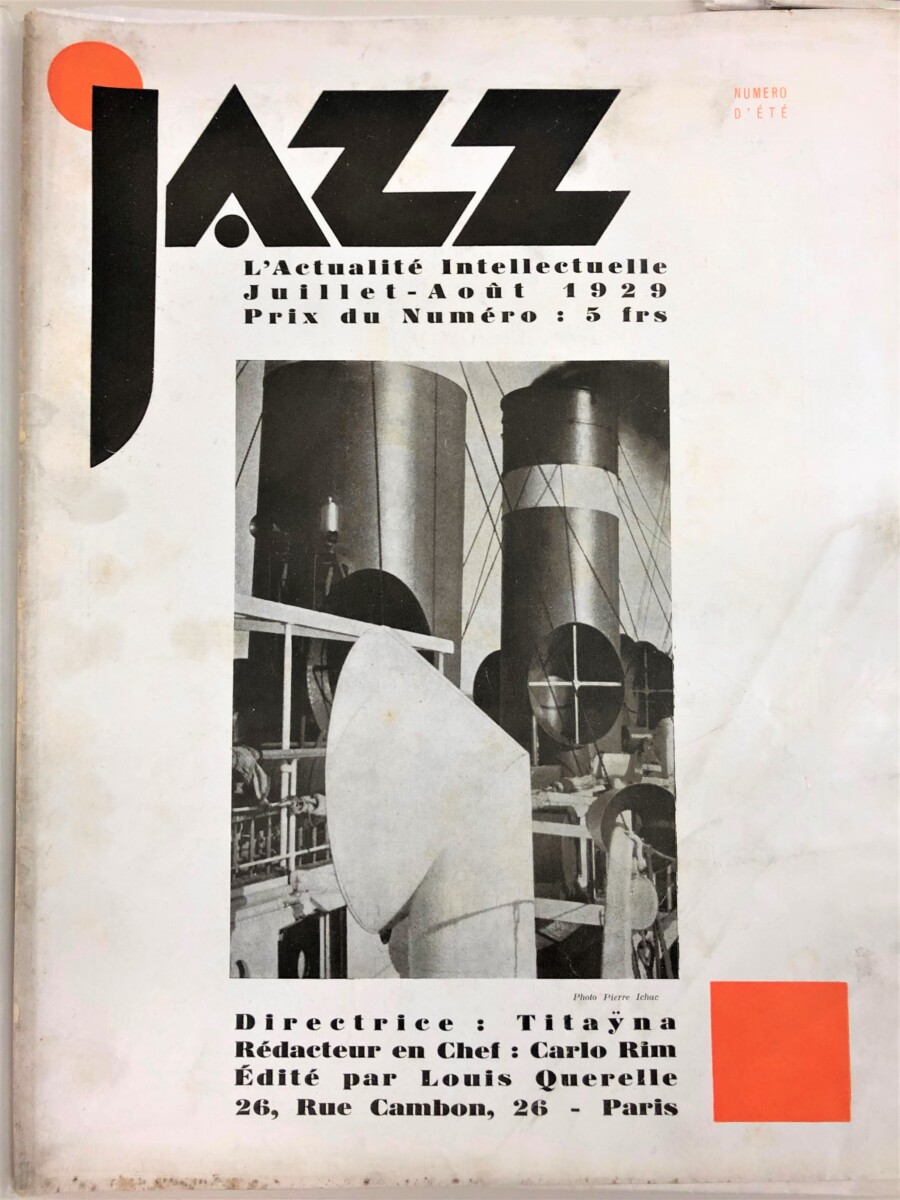

Jazz: L’Actualité intellectuelle (1928-1930?) was one of the new French photo journals (including Vu, Lu, and Voilà) of the Art Deco period that employed a multitude of avant-garde writers, illustrators, and photographers to attract artistic-minded and fashionable readers. These publications popularized the picture essay format, and the stunning photographs of great modern photographers, including Man Ray, Berenice Abbott, Germaine Krull, and Moholy Nagy, appeared frequently on the covers and in the pages of Jazz, a recent acquisition for Marquand Library.

Jazz, edited by Carlo Rim and Louis Querelle, with Titaÿna (Élisabeth Sauvy) as “Directrice” of the early issues, was a short-lived but ambitious monthly, running to only fifteen issues and two special numbers on themes entitled “Exotique” and “Nudisme” in 1931. Jean Cocteau, Rene Clair, Ivan Goll, George Grosz, Max Jacob, Pierre Mac Orlan, Marcel Pagnol, André Salmon, and many others contributed articles about artists and exhibitions, literature, the cinema, architecture and music, including jazz, which had taken Paris by storm during World War I and prompted the magazine’s title. With its modernist layout, illustrations by contemporary artists, and photographs created with sophisticated pre- and post-production manipulation of images, such as photomontage, all informed by Dadaist and Surrealist art, Jazz was meant to epitomize all things cool.

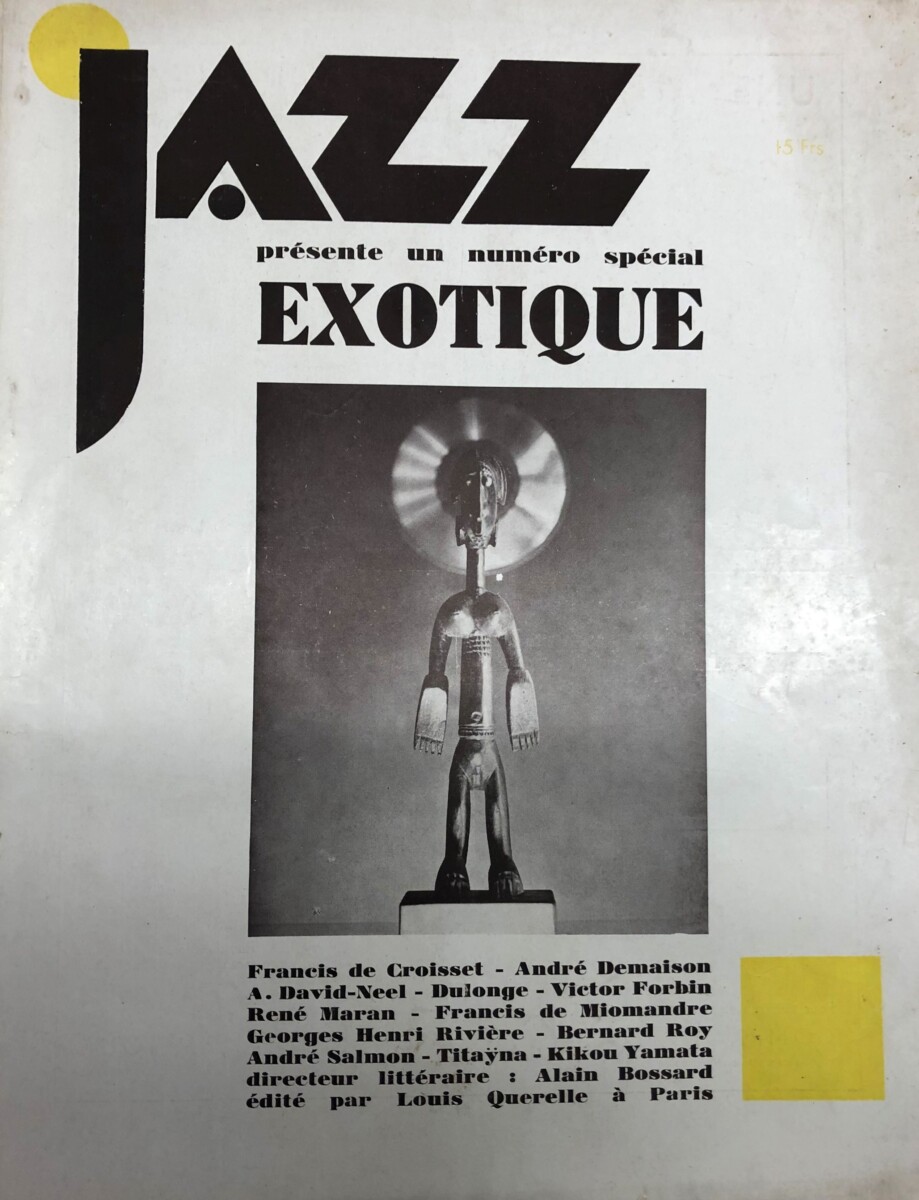

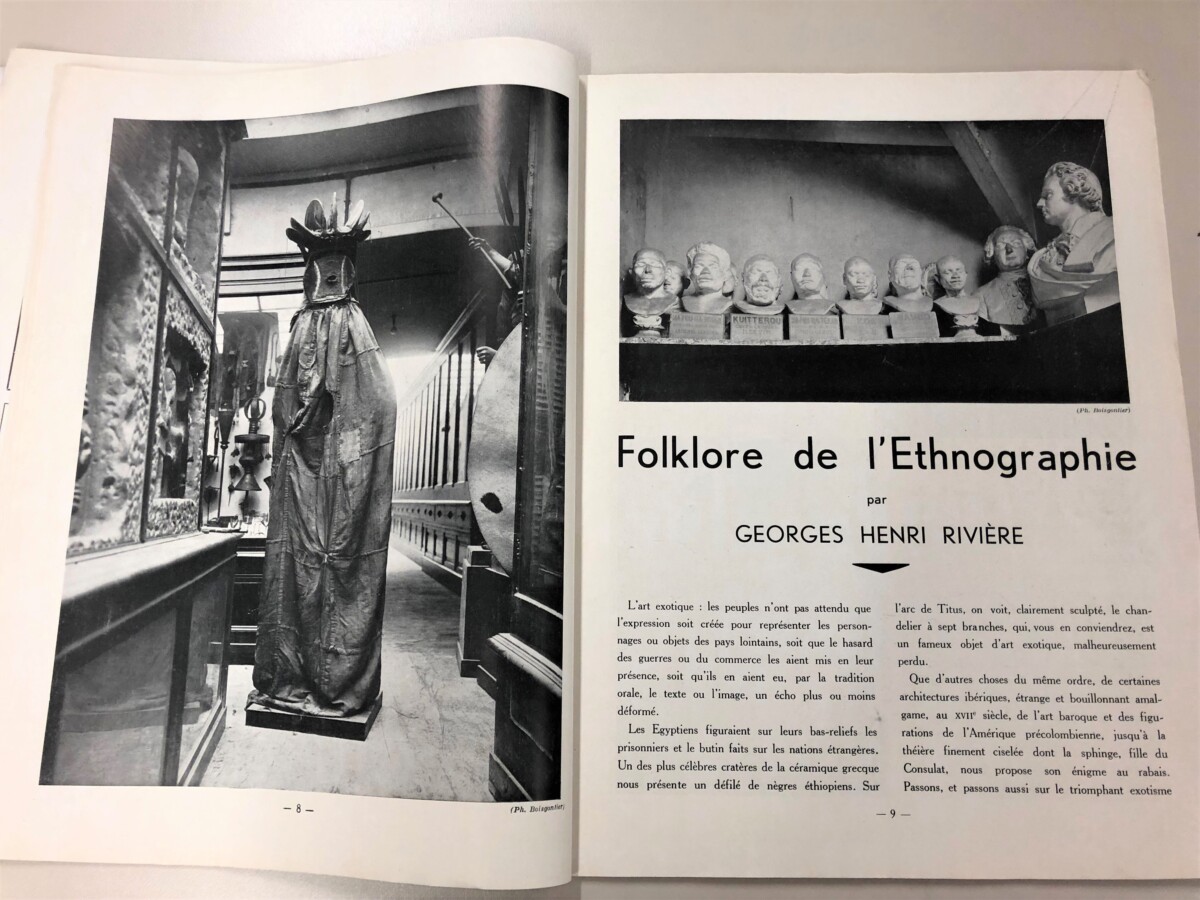

In spite of the magazine’s cosmopolitanism, the special number “Exotique” (1931) presents a complex and often shocking reflection of a bourgeois version of French avant-garde culture. The views expressed and the images used veer from adoration of the beauty and chic of “the other” — with articles on ethnographic art, Japanese Kabuki actors, and Tibetan sculpture, by knowledgeable authors — to the casual racism (both conscious and unconscious) that “exoticized” non-Caucasian and indigenous peoples and their art, and was clearly evident at the Colonial Exposition, taking place that year.

The extraordinary image on the cover, created by the ethnographic photographer Gilbert Boisgontier, juxtaposes a Bamana female jonyeleni sculpture (central Mali) with an image of a spinning cymbal, associated here with jazz music, placed behind the statue’s head to create a halo effect, which, in the words of Wendy A. Grossman “conflates a romanticized representation of an African sculpture with this African-African musical form.” 1

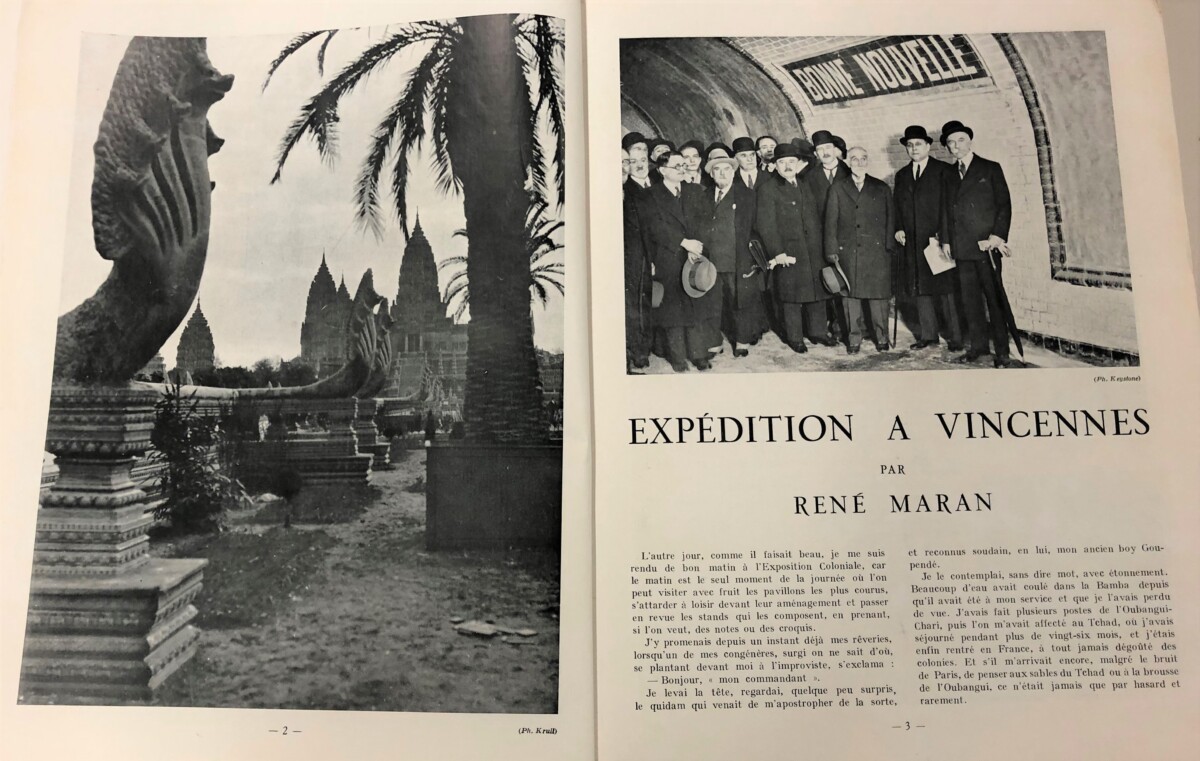

“Exotique” began with an account of a visit to the controversial Colonial Exposition at the Bois de Vincennes, outside Paris, where the organizers created a massive spectacle, intended to promote the “civilizing” and unifying benefits of colonialism. Other countries, including the Netherlands, Belgium, and the United States, with its recreation of George Washington’s Mount Vernon residence, built pavilions or contributed to exhibits, but the main focus was on the French colonies. From May-November, 1931, visitors could roam the spacious site, marveling at such wonders as the replica (by French architects) of the Angkor Wat temple, and view daily life in “authentic” African villages, while sampling ethnic foods and musical performances by workers from the colonial territories. There were also displays of art at the Musée Permanent des Colonies at Vincennes, as well as the “Exposition Ethnographique des Colonies Françaises” at the Musée Trocadéro. Though the Exposition was a financial success, with an estimated 8-9 million visitors2, by the 1930s, many were aware that all was not well with French colonialism.3 News of recent uprisings in Vietnam and of the huge death toll of forced laborers during the construction of the Congo-Ocean railroad featured heavily in left-wing press and propaganda, and anti-Imperialist groups railed against the Exposition and its attempts to glorify and justify colonial exploitation.

The LDNR (Ligue de Défense de la Race Nègre) organized a counter exposition at the Palais des Soviets (September 1931-February 1932). “La Vérité sur les Colonies” [The Truth about the Colonies] included its own display of art, including African and Oceanic pieces lent by André Breton, Paul Éluard, Tristan Tzara and other artists.3 The Surrealists, primed by the recent arrests of Tiemoko Garan Kouyaté, the French Sudanese leader of LDRN, and other left-wing dissidents, issued “Ne visitez pas l’Exposition Coloniale,” a tract urging people not to visit the Colonial Exposition. Yet the alternative exposition was also criticized, especially since it was based on the concept borrowed from the Colonial Exposition itself. And the sale of Breton and Eluard’s collection of African, Indigenous America and African art in Paris in July 1931 must surely have benefitted from the attendant publicity from both sides of the bitter controversy. Jazz ceased publication that year, and this was the last colonial exposition in France.

1Wendy A. Grossman, “Fashioning a Popular Reception,” in Man Ray, African Art and the Modernist Lens (2009), ch. 7, p. 129.

2Though some sources state that more than 33 million paid admissions occurred, many of these may have been repeat visitors.

3 See Jody Blake, “The Truth about the Colonies, 1931: Art indigène in Service of the Revolution. Oxford Art Journal 25.1 (2002), pp. 35-58.

Nicola Shilliam, Western Art History Bibliographer