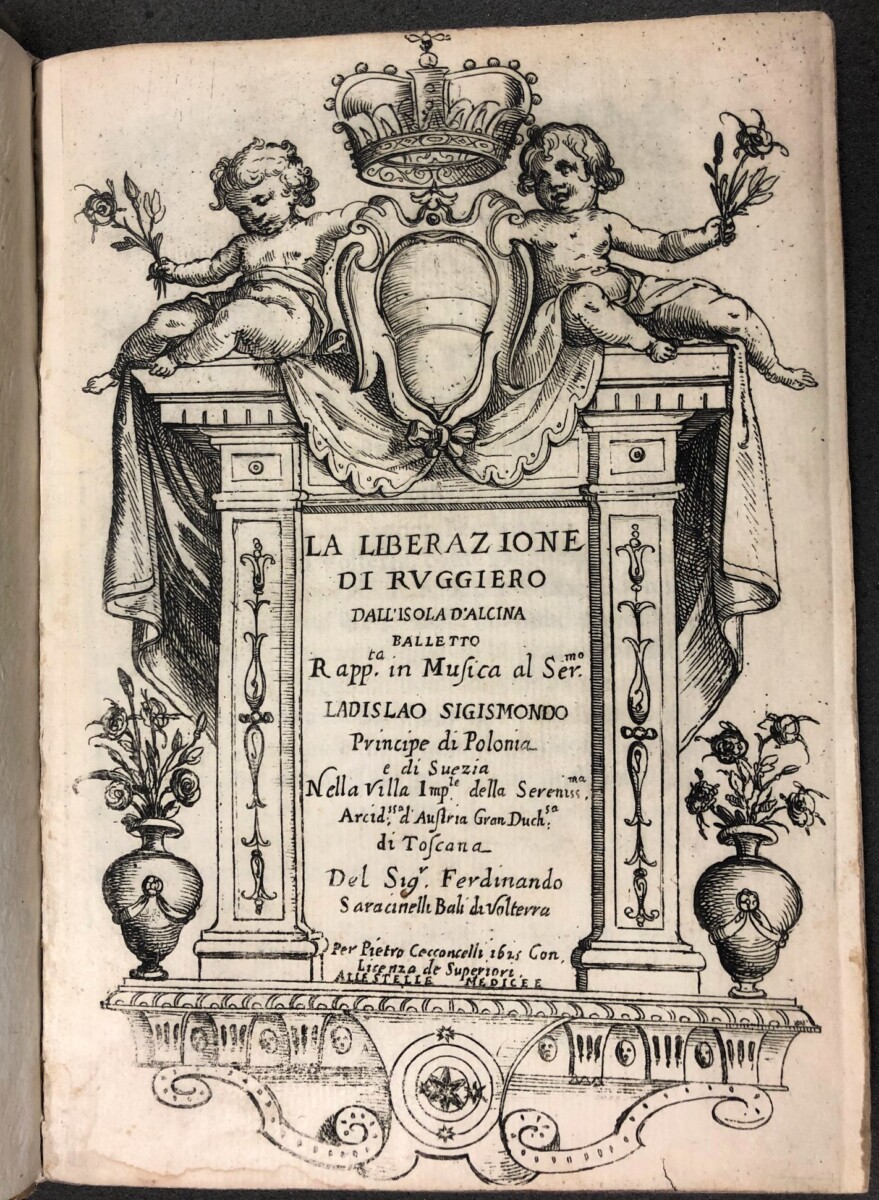

Ferdinando Saracinelli, La Liberazione di Ruggiero dall’Isola d’Alcina. Balletto rapp.ta in musica al Ser.mo Ladislao Sigismondo principe di Polonia e di Suezia nella villa imp.le della serenss.ma arcid.ssa d’Austria gran duch.sa di Toscana… Florence: Pietro Cecconcelli (1625)https://catalog.princeton.edu/catalog/99113265403506421

In Marquand’s rare books collection is a precious souvenir of the first performance of La Liberazione di Ruggiero dall’Isola d’Alcina…, considered to be the first opera composed by a woman – Francesca Caccini. The publication, illustrated with etchings by Alfonso Parigi after the sets designed by his father Giulio Parigi, served as a record of three entertainments performed for the visit of Prince Władysław Sigismund Vasa-Jagiellon, later king of Poland, to the Medici court in 1625. All three items in this specially created festival book feature female protagonists, in honor of the court’s female patron, Archduchess Maria Maddalena of Austria, co-regent of Florence with Christina of Lorraine, her mother-in-law, after the death of Maria Maddalena’s husband, Grand Duke Cosimo II de’Medici, in 1621.

Born in Florence in 1587, Francesca Caccini was the daughter of Giulio Caccini, the composer of L’Euridice (1600), itself thought to be the earliest surviving opera. Although Francesca was celebrated as both a composer, vocalist, and musician, and was the highest paid musician at the Medici court, this was her sole surviving opera and her name was not recorded alongside that of the male librettist on the the title page.

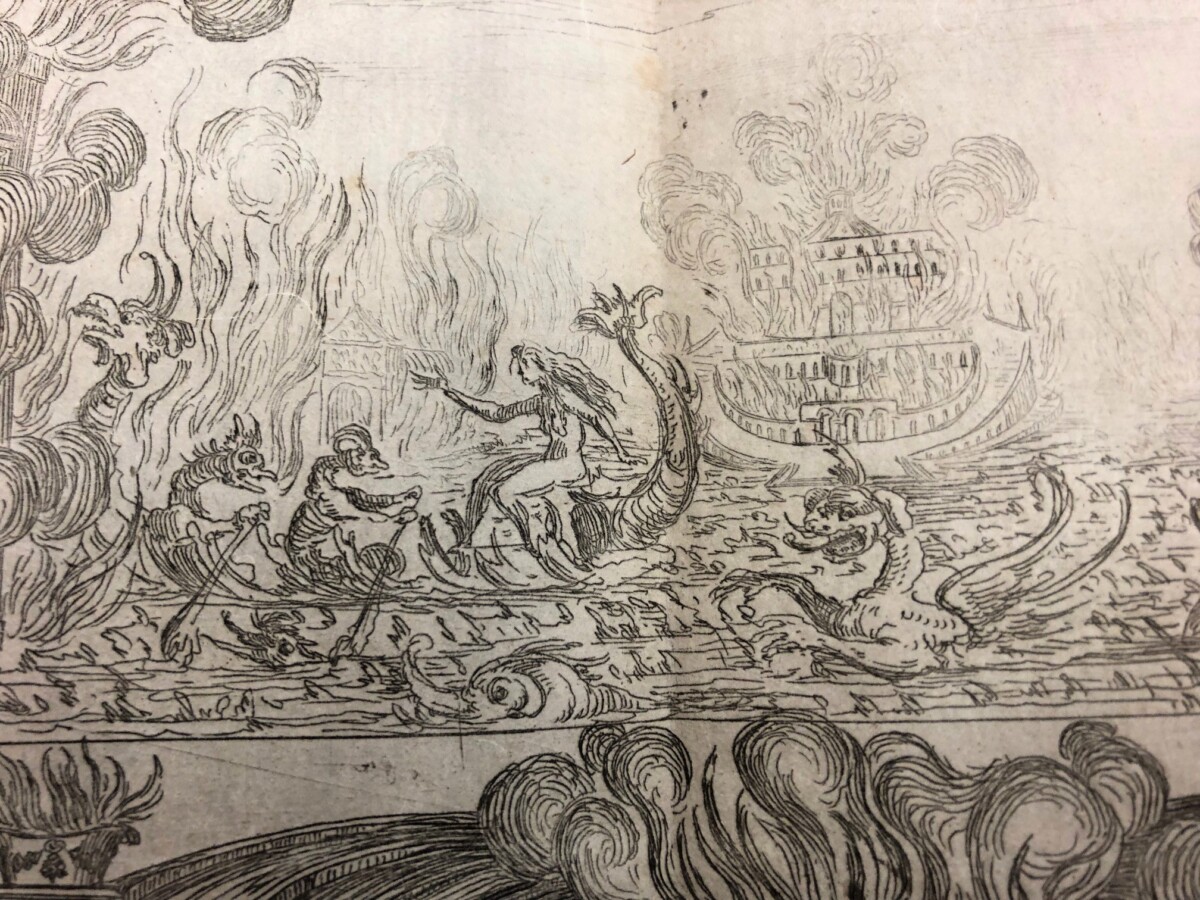

As described in the title, this opus is defined as a “balletto,” which combined singing, dancing, and a final “ballo a cavallo,” (equestrian ballet), common features of early Florentine opera. With a libretto by Ferdinando Saracinelli deriving from both Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso and Orlando Innamorato by Matteo Maria Boiardo, this comic opera in four scenes was performed for the first time at the Villa Poggio Imperiale on February 3, 1625, the time of Carnival. To honor the Polish visitor, Neptune (shown above) invited Vistula, the river god, to join him in recounting the story of Ruggiero for the audience.

This tale of two powerful women, the sorceresses Alcina and Melissa, dramatized their battle for control of the fate of Ruggiero, the multiracial son of a Christian knight and a Saracen princess, the daughter of Argolant, king of Africa. Like all good operas, the story was complex and fantastical: having been whisked away by a hippogriff from captivity in an enchanted castle, Ruggiero was deposited on the isle of Alcina. Bewitched by the sensual charms of Alcina, Ruggiero was unable to leave her island, and neglected his future wife Bradamante (another Christian knight, later featured in an opera by Handel). Arriving on the back of a dolphin, Melissa’s mission was to return Ruggiero to Bradamante, with whom he was destined to found the house of Este, who also happened to be the patrons of Ariosto and Boiardo.

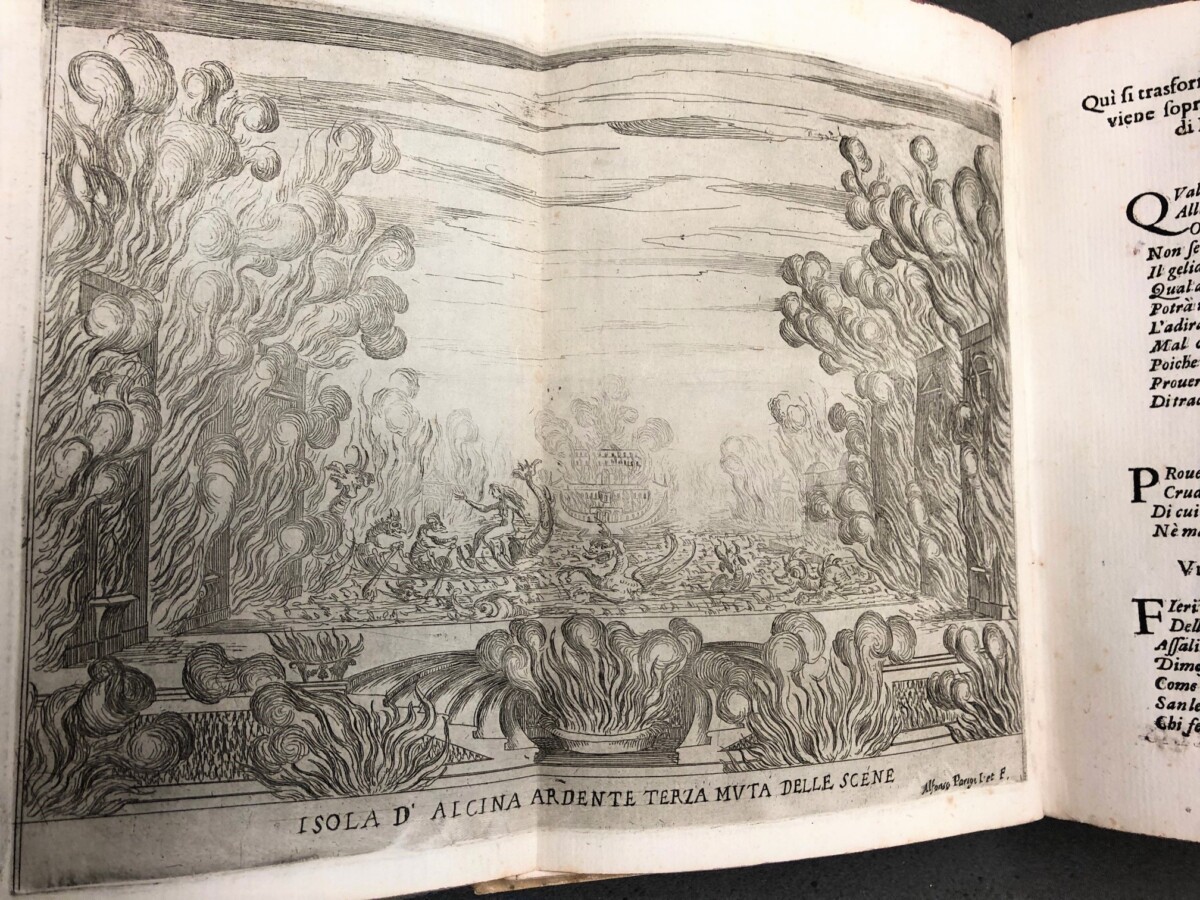

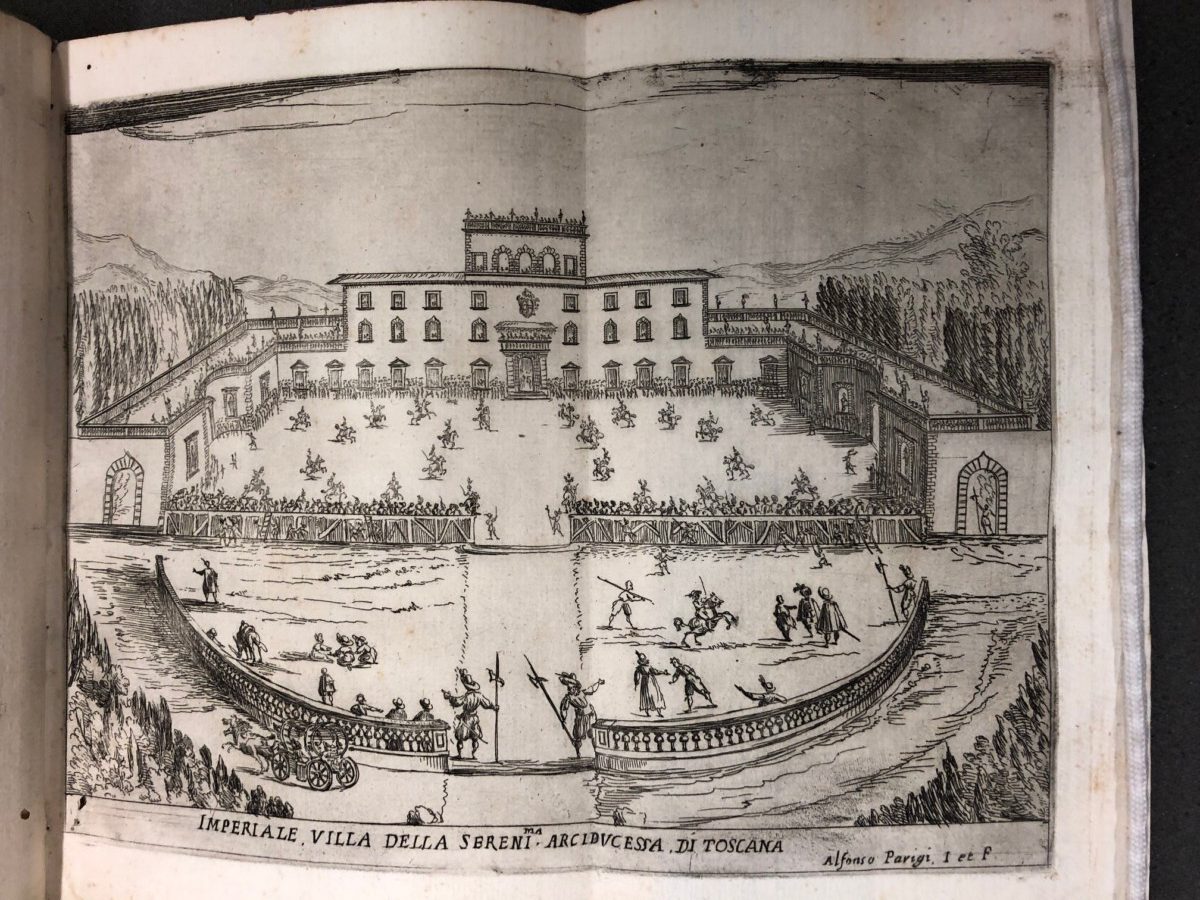

Once liberated by Melissa, Ruggiero could hear the cries for freedom of other victims of Alcina’s spells who had been transformed into flowers in her gardens. In the penultimate scene, young people leave their caves and dance. The dancers were recorded as members of the court rather than professional performers. In the background are faint images of the knights on horseback who would perform the final “ballo a cavallo” in the courtyard.

Alcina, enraged by the loss of her lover and the other captives, fled with her demonic retinue, having ignited her island with real flames, a display of pyrotechnics that forced the entire audience to evacuate their seats, and was intended to cause them to reflect on the powers of the Grand Duchess of Florence herself.

The performance took place at Villa Poggio Imperiale, which had recently been renovated by Giulio Parigi, the Medici court architect, for the Grand Duchess. While the other plates depict performers against painted backdrops with spectacular changes of scenery, this plate provides a valuable record of the exterior of the palace, where the equestrian ballet occupied the entire courtyard: the palace was destroyed in the eighteenth century.

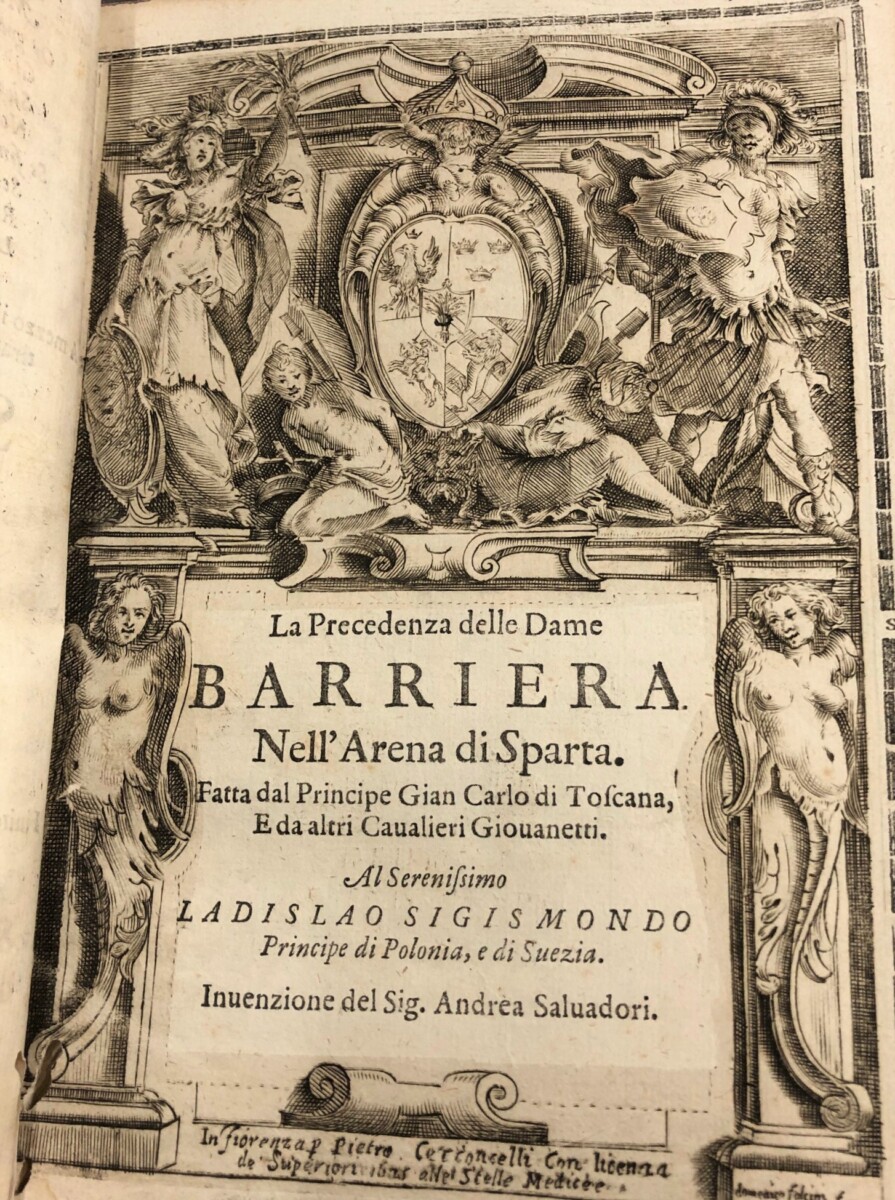

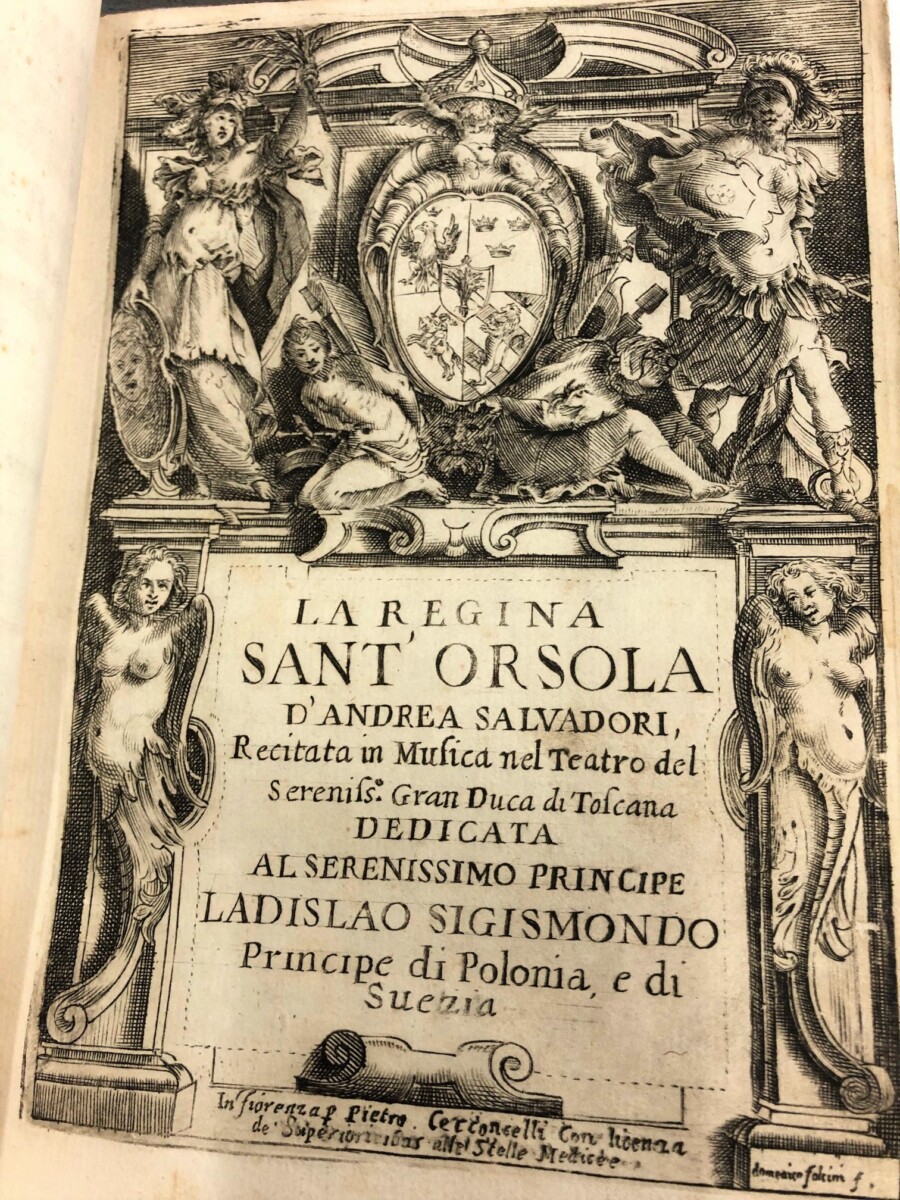

The other two works in this festival book were also female-centred, multi-media performances. La Precendenza delle dame…, created by the Florentine librettist Andrea Salvadori, was sponsored by Cardinal Gian Carlo de’Medici, Maddalena’s son. Dedicated to the “beautiful women of the world,” La Precedenza included a joust and another horse ballet, performed by young men of the court. Set to music by Jacopo Peri, again with designs by Giulio Parigi, La Precedenza enacted a battle between Mars, accompanied by the young men of Sparta, and Athena, supported by the young women of Sparta, who were triumphant. The third entertainment, La Regina Sant’Orsola, a long “recitata in musica,” performed in the Grand Ducal theatre, concluded with the ascension of the virgin martyr Saint Ursula to heaven.

To enjoy a fuller experience of Francesca Caccini’s opera, an audio version of a performance of La Liberazione di Ruggiero, recorded on November 10, 2016 at the Oratorio del Gonfalone di Roma is accessible through the Princeton University Library catalogue.:

https://catalog.princeton.edu/catalog/10806943

A 1998 facsimile of Caccini’s musical score, which was not included in this 1625 publication, is also viewable at Princeton’s Mendel Library: