Utagawa Kunisada (1786-1864) is often considered the leading woodblock print artist of the 19th century. A “superstar” in his own time, much of his fame and popularity can be credited to his beautiful and dynamic book illustrations parodying the classic Tale of Genji. Marquand Library recently acquired three of Kunisada’s most important Genji masterpieces, often referred to as the “The Three Genji” (San Genji)1: The Amorous Murasaki Finds Pleasure in Fifty or More Chapters [Enshi gojūyo jō] (1835); Deep Feelings of Birds and Flowers: Genji of the East [Kachō yojō Azuma Genji] (1837); and A True-Life Devoted Genji [Sho-utsushi aioi Genji] (ca.1851). All three are erotica and were therefore illegally published. The first two titles may actually have been part of the 1842 government burning of eleven of Kunisada’s erotic books–and the woodblocks used to print them. According to an investigator’s report, Kunisada may have been tipped off to the raid because the artist had just left on a long pilgrimage to the Ise Shrine.

The Tale of Genji (Genji monogatari) is the most important work of classical literature in Japan. Written around the year 1000 C.E. by Murasaki Shikibu, a lady-in-waiting to the empress, it is heralded as world’s first novel. Like Shakespeare in the West, allusions to Genji permeate Japanese culture even today. It is, however, important to understand not only the iconic nature of this book, which is over 1000 pages in its English translation, but also the 19th century audience’s love of literary and illustrative parody in contemporary books and woodblock prints.

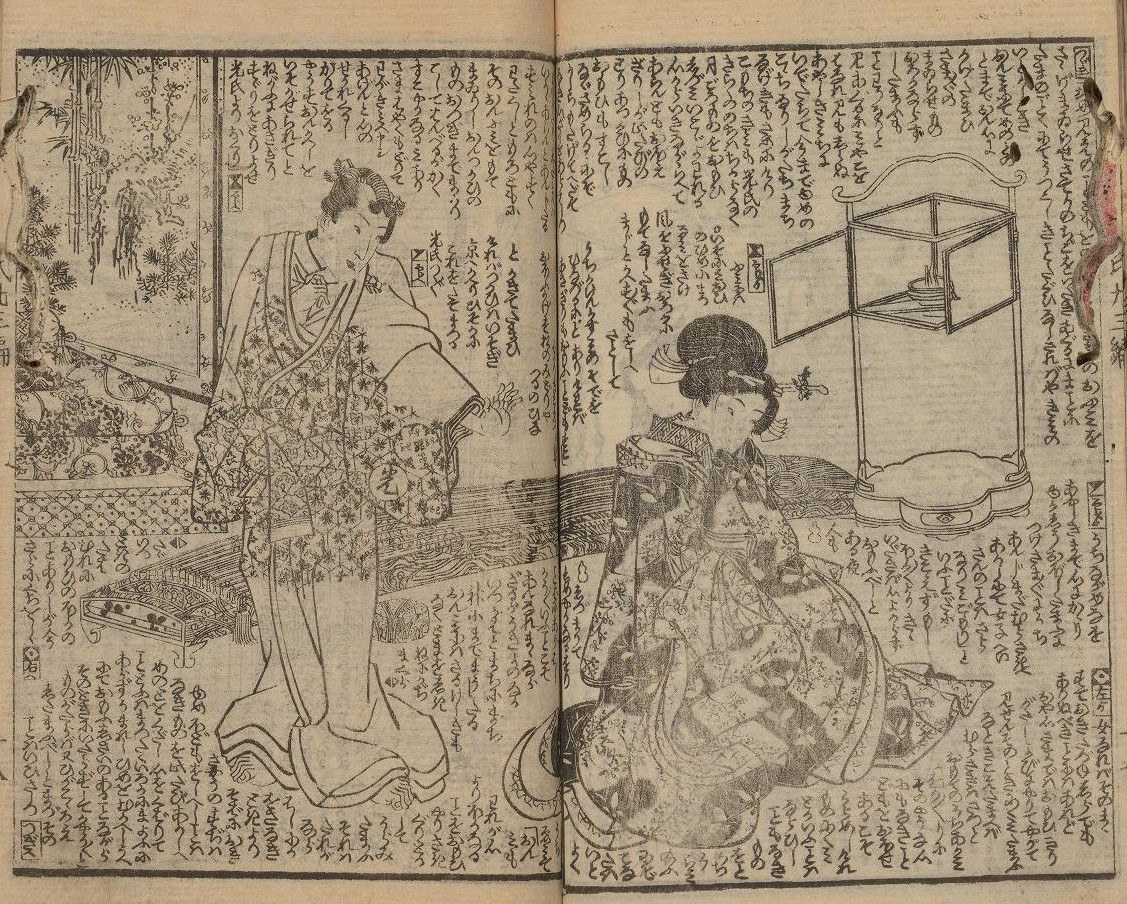

Ryūtei Tanehiko and Utagawa Kunisada,

Nise Murasaki inaka Genji (Parts 23-24)

Edo: Tsuruya Kiemon ca. 1837-1839

Courtesy of the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives (https://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/nisemurasakiina00ryuy)

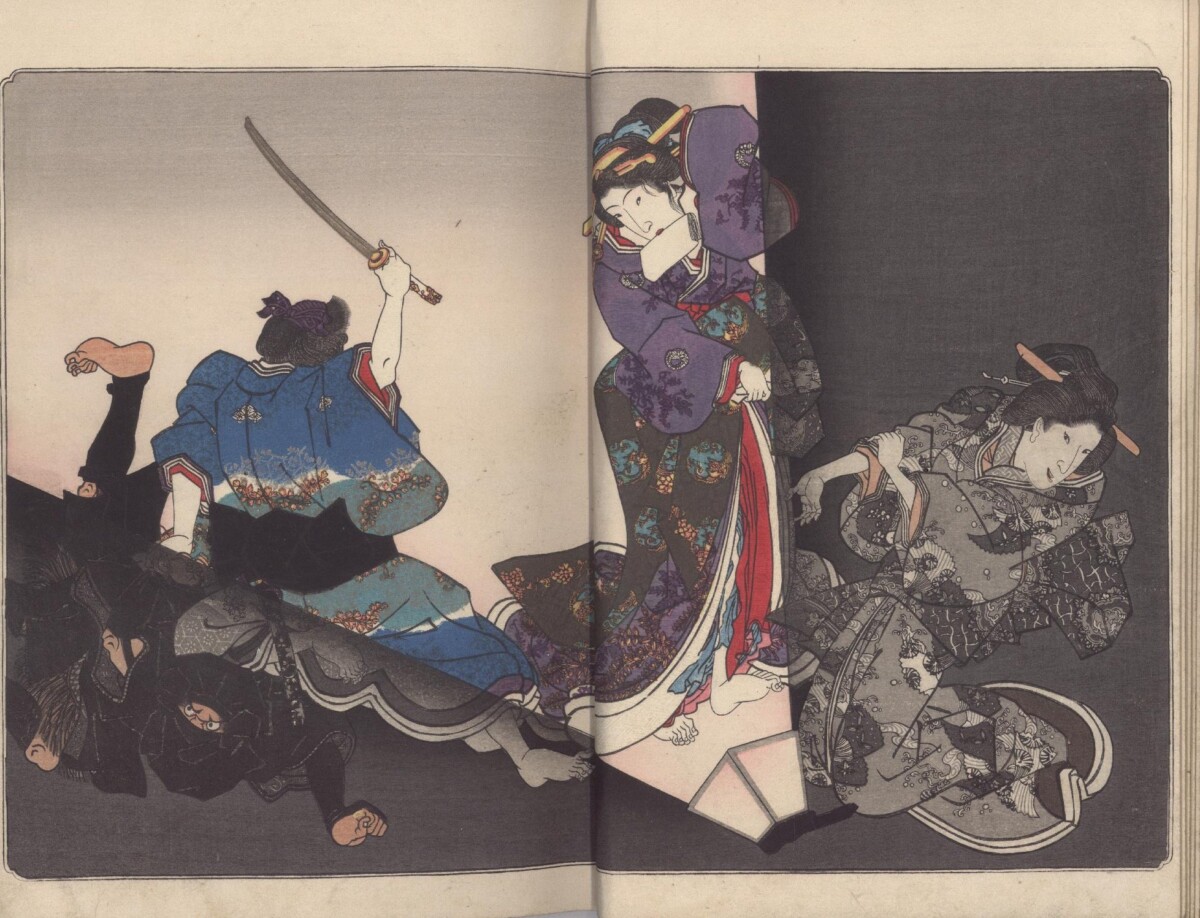

Between 1829 and 1842, the author Ryūtei Tanehiko (1783–1842) wrote a wildly popular parody of The Tale of Genji. Known as “The Rustic Genji” [Nise Murasaki inaka Genji]. The serially published volumes were illustrated by Kunisada and printed in black & white. Like Genji, the hero of the classical tale, Tanehiko’s protagonist, Mitsuuji, had many amorous adventures, which were then discretely illustrated by Kunisada. Brisk sales and Mitsuuji’s romantic escapades, however, appear to have sparked the idea to create erotic and more luxurious versions of Rustic Genji with its original illustrator.

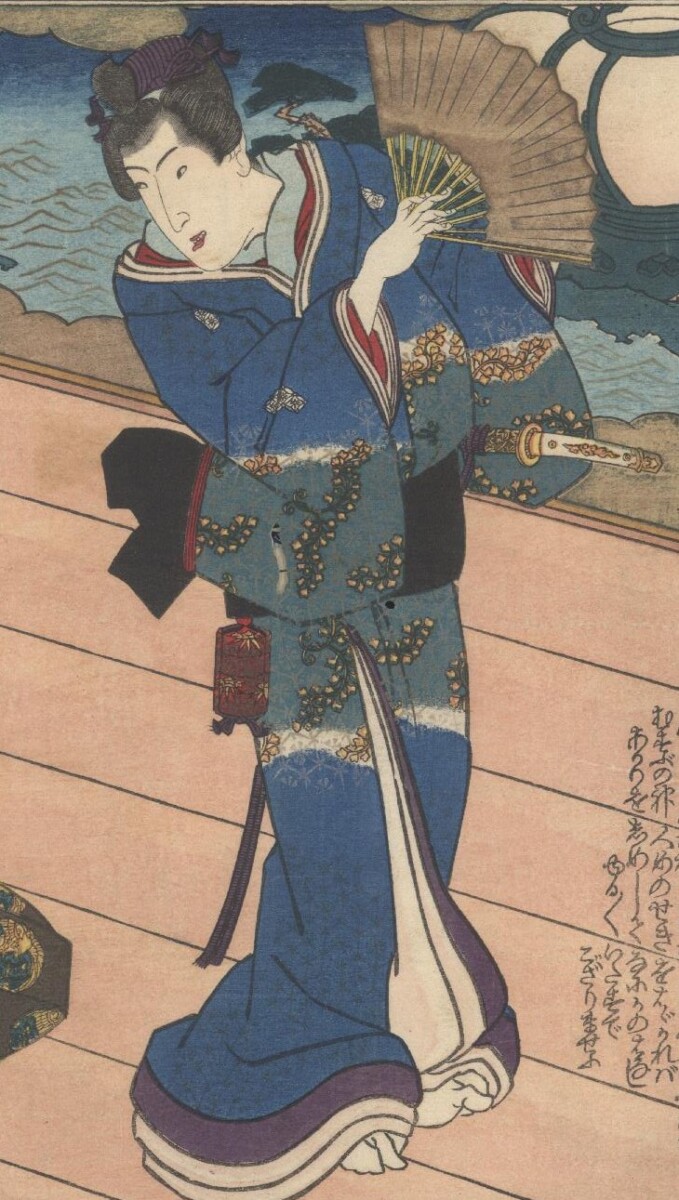

All three of these Kunisada titles are 3-volume sets and are extravagantly produced first editions. They are printed in rich expensive color on thick luxurious paper. The images have been enhanced with embossing, mirror printing,2 metallic pigments, gold leaf, mica and crushed mother-of-pearl. Perhaps most striking is Kunisada’s use of a deeply saturated Prussian blue (berorin-ai), a synthetic pigment which had only recently been imported from Europe.

The lavish printing of these books suggests private sponsorship for an elite audience, but after these expensive first editions were printed, the same woodblocks would be used to print runs of cheaper versions for the general public. These subsequent editions of Genji-themed books proved to be so popular and profitable that they established Kunisada as a premier artist of erotica, which continued to be the most popular subject matter of Japanese books and woodblock prints in the 19th century.

The first two of the “Three Genji” were published concurrently with new chapters of Rustic Genji, but in 1842, a rumor circulated that, although couched as a parody of the classic tale, the serialized story was really about the goings-on in the Shogunal harem in Edo Castle.3 Rustic Genji was banned with only 38 of the 54 chapters published. Tsuruya Kiemon, the series’ publisher, was prosecuted and left bankrupt. The author, Ryūtei Tanehiko died in custody after questioning. As mentioned earlier, Kunisada avoided prosecution, deciding to take a last minute pilgrimage. He may indeed have been tipped off by the elite samurai sponsors his erotic books. He also changed his name to Toyokuni, which some scholars believe may also have helped.

It was not until 1851 that the third Kunisada Genji-themed erotica of the set was published. In the first two titles, Kunisada had hidden his pseudonym4 within a print in each volume. In this book, perhaps more cautious, he did not. This third title is the most luxuriously created of the three. It is believed to have been privately published by the samurai lord and son of Tokugawa Ienari, Matsudaira Yoshinaga (1828-1890), as a gift for friends. Marquand’s copy is particularly remarkable in that it retains its original wrapper (see below). Although beautifully printed, these book wrappers were often discarded by their owners.

Erotic versions of the Tale of Genji were popular from the 17th century onward. Marquand Library actually owns what is considered the earliest extant edition of Genji erotica, Genji’s Elegant Pillow (Genji kyasha makura), dated 1676. More about that in a future post, but enjoy seeing this book here.

- * Because most of the images from these books are very graphic and may offend, I have chosen the few discrete images available to illustrate this post. If you wish to see an example of a more typical image, an illustration from Deep Feelings of Birds and Flowers: Genji of the East, please click here.

- 1. Timothy Clark, et al., eds. Shunga: Sex and Pleasure in Japanese Art. London: British Museum, 2013, p. 238.

- 2. shomen-zuri (front printing) is a burnishing technique, which was used to make the black lines/ areas of woodblock prints shiny.

- 3. ibid., p. 237. Another scholar suggests that the books may have been banned because the price had become so high as to violate sumptuary laws. (p. 233)

- 4. Bukiyo Matahei (Matabei)

- 5. Sebastian Izzard, Utagawa Kunisada: His World Revisited (Exhibition catalog) March, 2021, p. 154.

- 6. Timothy Clark, et al., eds. Shunga: Sex and Pleasure in Japanese Art. London: British Museum, 2013, p. 241.